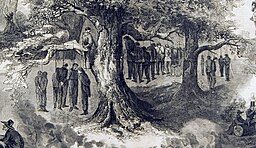

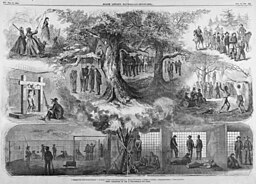

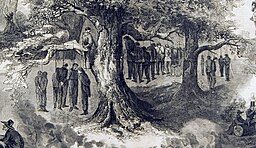

Great Hanging at Gainesville, Texas, during the Civil War - October, 1862. Illustration for Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 20 Feb 1864, page 354.

Introduction

In the autumn of 1862, as the Civil War raged across the nation, a quiet frontier town in North Texas became the site of one of the most chilling acts of internal violence in American history. Gainesville, the seat of Cooke County, was far from the great battlefields of the war; yet its courthouse square bore witness to an episode so brutal that it would stain the community’s memory for generations. Fears of hidden Unionist plots, inflamed by wartime hysteria and the defense of slavery, erupted into what came to be known as the Gainesville Hangings. In the span of just a few weeks, more than forty men—farmers, ministers, and neighbors—were executed without due process, most by hanging. This mass execution, the largest in the United States outside of battlefield slaughter or Native American conflicts, revealed the terrifying speed with which fear can silence law, fracture communities, and unleash tragedy.

Background and Causes

When Texas seceded from the Union in 1861, North Texas presented a special problem. The region had relatively few enslaved people compared to the eastern plantations, and many settlers—many of them small farmers with roots in the Upper South or Midwest—opposed secession. Confederate authorities feared disloyalty, draft resistance, and even armed uprisings in the area. In the summer of 1862, following the passage of the Confederate Conscription Act, which required military service, resentment intensified. Rumors spread of a so-called “Union League” conspiring against Confederate rule, though concrete evidence of such an organized threat has never been found.

Although slavery was not as economically entrenched in North Texas as in East Texas, many white settlers there still strongly defended it. Their reasoning went beyond immediate economic need and was grounded in ideology and social order. Most white Southerners, including those in frontier regions, believed African Americans were racially inferior and viewed them primarily as property rather than as human beings with equal rights. For them, if the government could abolish slavery, it might also undermine broader property rights. Protecting slavery meant protecting the very principle of ownership that defined much of their society. Even non-slaveholders benefited from a system where slavery created a racial hierarchy, placing poor whites above enslaved people and reinforcing their social status. The idea that emancipation could lead to African Americans gaining legal or political equality was seen as an existential threat to the Southern way of life. Added to this was the practical matter of security: North Texas bordered Indian Territory, where both Union and Confederate forces operated. Confederate leaders believed that dissenters in such a vulnerable frontier zone endangered the community’s stability. Supporting slavery and the Confederacy thus became intertwined with loyalty, security, and identity, explaining why North Texans—despite having relatively few enslaved people—reacted so violently to suspected Unionist sympathies.

The Citizens Court and Executions

On October 1, 1862, local militia arrested more than 150 men suspected of Unionist sympathies and brought them to Gainesville. A “Citizens Court” was hastily organized, made up of twelve men appointed by Colonel William C. Young, a Confederate officer and local planter. Unlike the legally recognized county or state courts of Texas, this body had no official sanction under Confederate or state law. Instead, it resembled the vigilance committees sometimes formed in frontier communities to deal with cattle theft or violent crime. Yet in this case, the tribunal was applied to alleged political disloyalty on an unprecedented scale, making it extraordinary and controversial even in its own time. The proceedings were deeply flawed. Defendants had no legal counsel, and guilt was often assumed more than proven. Local law enforcement did not intervene to halt the actions, and county officials were generally aligned with Young and the pro-Confederate faction. Appeals for mercy from certain community members went unheard, and state authorities in Austin declined to interfere. The absence of opposition from both local and state officials meant that the killings proceeded unchecked.

Within days, the jury voted to send dozens of men to the gallows. The first executions occurred on October 4, and by mid-October, forty men had been killed, thirty-nine of them hanged and one shot while attempting escape. Another two were lynched by mobs after the formal trials ended. Among the executed were prominent local residents whose stories reveal the human cost of the hysteria. Reverend Nathaniel M. Clark, a Methodist minister, was hanged despite pleas for mercy from his congregation. Brothers Ephraim and Henry Chism were executed together, illustrating how entire families could be targeted. John Jackson Crisp, a farmer with little influence, was condemned on weak evidence, yet still sent to the gallows. Hiram Kilgore, another farmer accused of Unionist ties, was executed without proof of guilt. James M. Young, who bore no relation to Colonel William C. Young, was hanged despite efforts by friends to defend his loyalty. Others, like William Boyles and Richard N. Hopson, were accused of conspiring against the Confederacy and suffered the same fate. These names, preserved through historical records, remind us that the Gainesville Hangings claimed not only anonymous lives but also neighbors, preachers, and community leaders who had once been integral to Cooke County society.

Community Reaction

The hangings divided Cooke County and neighboring areas. Pro-Confederate families supported the actions, believing them necessary to suppress treason, and Confederate newspapers generally portrayed the executions as justified measures to defend the South. In contrast, Northern papers denounced them as atrocities, with some labeling the event “judicial murder.” Reports circulated of mobs chanting for blood and of prisoners pleading their loyalty before being hanged, adding to the sense of brutality. Neighbor-against-neighbor accusations further deepened the fracture, with some men condemned by those who had lived alongside them for years. This personal betrayal heightened bitterness and left wounds that outlasted the war. Some residents opposed the killings, but the climate of fear silenced dissent, as those who spoke out risked being branded traitors themselves.

After the war, Cooke County largely avoided public discussion of the hangings. Families of the executed concealed their connections to avoid stigma, while pro-Confederates defended the actions as necessary for survival. This silence shaped local memory for generations, leaving the Gainesville Hangings both a source of shame and a reminder of how wartime hysteria could divide communities at their core. Confederate authorities in Richmond and Austin did not intervene, leaving the responsibility to local leaders. The killings left a legacy of fear and silence among surviving families, many of whom fled the region.

No one was ever charged or punished for the Gainesville Hangings. Colonel Young was killed later that year in a skirmish with Native Americans, ending any possibility of his being held accountable. Confederate leaders largely ignored the event, prioritizing the broader war effort over local atrocities. In the postwar years, the Gainesville executions became symbolic of the extreme internal divisions within Texas, illustrating how fears of disloyalty could escalate into mass violence.

Significance

The Gainesville Hangings reveal the intense pressure of wartime loyalty in Confederate Texas. They underscore how suspicion of Unionism—sometimes exaggerated, sometimes real—led to extrajudicial killings. The scale of the executions shocked contemporaries and remains a stark reminder of the costs of civil war beyond the battlefield. They also demonstrate how fragile community bonds could become under the strain of war. Neighbors turned on one another, and local leaders chose violence over legal order, showing how civil institutions could collapse when fear outweighed law. The hangings further illustrate the reach of slavery’s ideology: even in a region with few enslaved people, the defense of the system—and the racial hierarchy it upheld—was strong enough to justify mass executions. In the broader history of the Civil War, Gainesville stands as a chilling example of internal repression within the Confederacy, reminding us that the war was fought not only on distant battlefields but also within divided communities where fear and suspicion bred tragedy.

Conclusion

The Gainesville Hangings of 1862 remain one of the most sobering episodes in Texas history. What began as whispered fears of disloyalty ended with neighbors hanging neighbors in the town square, while law and justice were replaced by suspicion and vengeance. It was not the roar of cannons or the clash of armies that tore Cooke County apart, but the corrosive power of fear and the determination to preserve a social order built on slavery. In remembering the names of those executed, we confront the reality that civil war is never fought only between armies—it invades households, churches, and communities, leaving scars that outlast generations. The lesson of Gainesville is both simple and painful: when fear overrules justice, and ideology eclipses humanity, the result is tragedy on a scale that can never truly be undone.

Sources and Bibliography

Abby Rapoport, “How Do You Memorialize a Mob? Gainesville, Texas, Grapples with The Great Hanging,” Texas Observer, November 17, 2014, 1–3texasobserver.orgtexasobserver.org.

Thomas Barrett, The Great Hanging at Gainesville, Cooke County, Texas, October A.D. 1862 (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1961), 2babel.hathitrust.org.

Barrett, The Great Hanging at Gainesville, 3babel.hathitrust.orgbabel.hathitrust.org.

Richard B. McCaslin, Tainted Breeze: The Great Hanging at Gainesville, Texas, 1862 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994), 1–20.

Core secondary & reference works

- Richard B. McCaslin, Tainted Breeze: The Great Hanging at Gainesville, Texas, 1862 (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1994). Authoritative monograph; chronology, causes, court mechanics, and numbers. TCU Personal Page

- Richard B. McCaslin, “Great Hanging at Gainesville,” Handbook of Texas Online (Texas State Historical Association). Clear overview, dates, and totals; cross-references to key figures. TSHA Online

- “Young, William Cocke,” Handbook of Texas Online (TSHA). Details Young’s role and death in October 1862, which triggered further hangings. TSHA Online

- “Bourland, James G.,” Handbook of Texas Online (TSHA). Provost who led the arrests; biographical context. TSHA Online

- “Hébert, Paul Octave,” Handbook of Texas Online (TSHA). Context for his dismissal over martial law/conscription policies that frame North Texas unrest. TSHA Online

Primary accounts (critical for names and proceedings)

6. Thomas Barrett and George Washington Diamond, The Great Hanging at Gainesville, 1862: The Accounts of Thomas Barrett and George Washington Diamond, ed. with intro. by Richard B. McCaslin (College Station: TSHA/Texas A&M University Press, 2012). Collates the two 19th-c. narratives used by scholars. Texas A&M University Press

7. Thomas Barrett, The Great Hanging at Gainesville, Cooke County, Texas, October, A.D. 1862 (1885; TSHA reprint, 1961). Contemporary juror’s account; helpful for sequences and some names. library.missouri.edu

8. “George Washington Diamond Narrative, 1862–ca. 1876,” Dolph Briscoe Center finding aid (TARO). Archival pointer to the Diamond manuscripts used in #6. Texas Archives

High-quality reportage & public history (useful for corroboration and community reaction)

9. Dallas Morning News, “Gainesville to commemorate still-controversial ‘Great Hanging’ of 1862” (Oct. 17, 2014). Strong event timeline: Oct. 1 arrests; Oct. 4 first seven hangings; simple-majority rule; 14 lynched; later 19 hanged; community debate. Dallas News

10. Abby Rapoport, “Gainesville, Texas, Grapples with The Great Hanging,” Texas Observer (Nov. 17, 2014). Juror composition (majority slaveholders), post-Young escalation, and 2014 memorial context. The Texas Observer

11. American Battlefield Trust, “The Great Hanging Memorial.” Brief, reliable summary; memorial details and victim count range. American Battlefield Trust

12. Texas Historical Commission Atlas, “Great Hanging at Gainesville” historical marker listing (site location and designation). Texas Heritage Commission Atlas