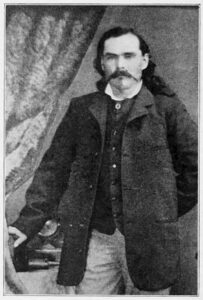

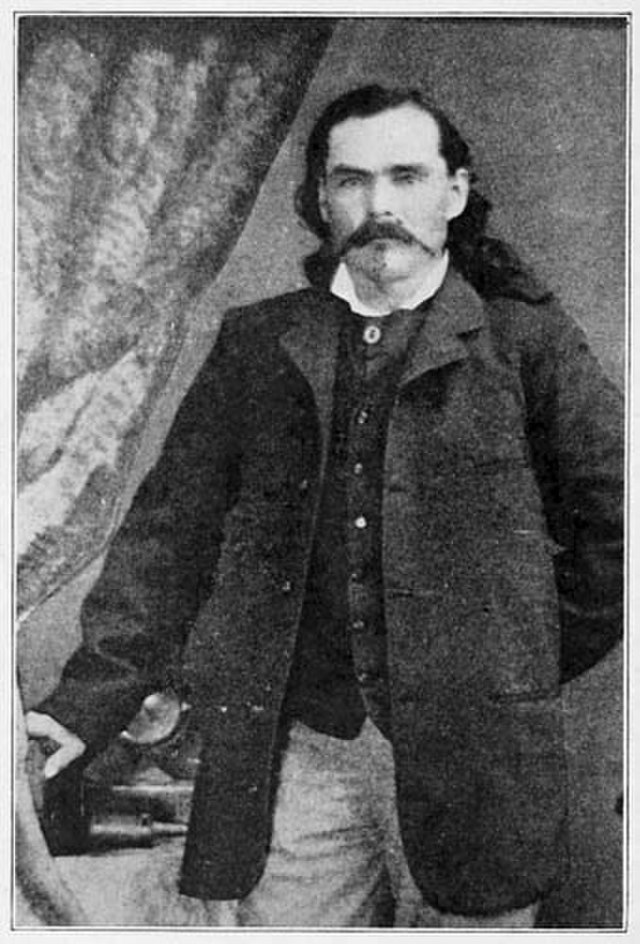

Billy Dixon

Dedicated to my friend, Billy Dixon [not the one in the story :)]

Early Life and Family Background

William “Billy” Dixon was born on September 25, 1850, in Ohio County, Virginia (today West Virginia)[1]. He was the eldest of three children, but tragedy struck early in his life. His mother died when he was a boy, and by age 12, he had lost both parents, leaving him orphaned[1]. Billy and his younger sister went to live with their uncle, Thomas Dixon, in Ray County, Missouri.[1] Independent and hardy by nature, Billy stayed only about a year with his uncle before striking out on his own as a young teenager[2].

Dixon was determined to make his own way. In 1864, at just 14, he found work in woodcutters’ camps along the Missouri River and soon became an ox-team driver (or “bullwhacker”) and muleskinner for a government freight contractor in Kansas.[3] For about a year in 1866, he left freighting to work on a farm near Leavenworth, Kansas – an experience that provided the only formal schooling of his life[3]. By the late 1860s, Dixon was fully engaged in the booming frontier economy: hauling freight across the Plains and absorbing tales of adventure from veteran frontiersmen. These early experiences hardened him and fueled his desire for a life of adventure on the Great Plains.[4][5]

Buffalo Hunting and Frontier Life

After several years on the freighting trails, Billy Dixon transitioned to buffalo hunting – a highly lucrative but rough vocation during the post-Civil War era. In November 1869, he joined a hunting and trapping outfit along the Saline River in Kansas, where his natural marksmanship quickly proved profitable[6]. At the time, buffalo hides were in great demand; buyers paid about $1 for cow hides and $2 for bull hides in 1870, tempting many young frontiersmen to become professional hunters[7]. Dixon’s skill with the rifle made him especially successful – it was said that after the great buffalo migrations, he “could shoot enough buffalo to keep ten skinners busy,” an indication of his extraordinary accuracy and productivity as a hunter[8].

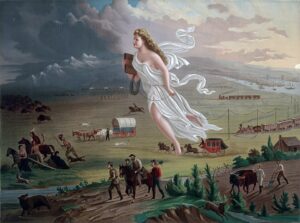

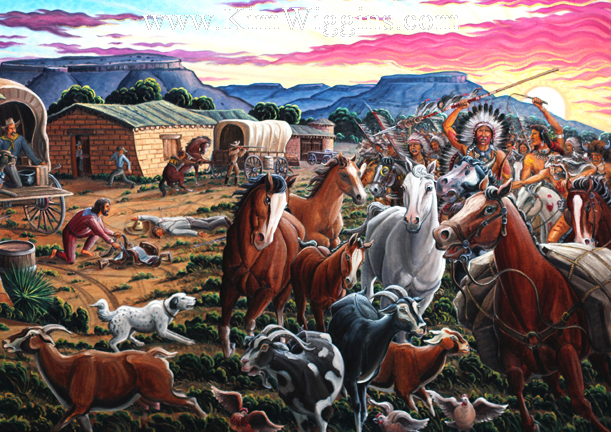

By 1872–73, Dixon was operating out of the new boomtown of Dodge City, Kansas, then known as the “Buffalo Capital of the West.”[9][10] He even invested his earnings in a small supply outpost (a “road ranch”) to serve fellow hide hunters. This venture was short-lived, however – in 1871, while Dixon was away on a hunt, his unscrupulous partner sold the store and disappeared with the profits[11]. Undeterred, Dixon returned to the buffalo range. He sometimes employed four or five skinners at a time to process the huge numbers of bison he shot[12]. By 1874, the great southern herd of buffalo was dwindling north of the Arkansas River, so Dixon and other hunters pushed down into the Texas Panhandle in search of new hunting grounds[13]. There, along the Canadian River in what is now Hutchinson County, Texas, he and a group of fellow hunters and Dodge City merchants established a trading camp near the ruins of old Bent’s Fort trading post known as Adobe Walls[14]. This “new” Adobe Walls consisted of a few adobe buildings – stores, a saloon, a blacksmith shop – and became a base for buffalo hunters in the region[15][16]. The presence of dozens of hunters in the heart of the Plains tribes’ buffalo range, however, was about to spark a violent confrontation.

The Second Battle of Adobe Walls (June 1874)

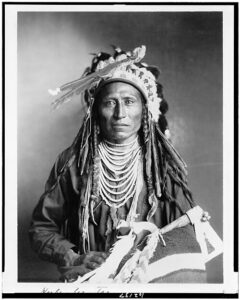

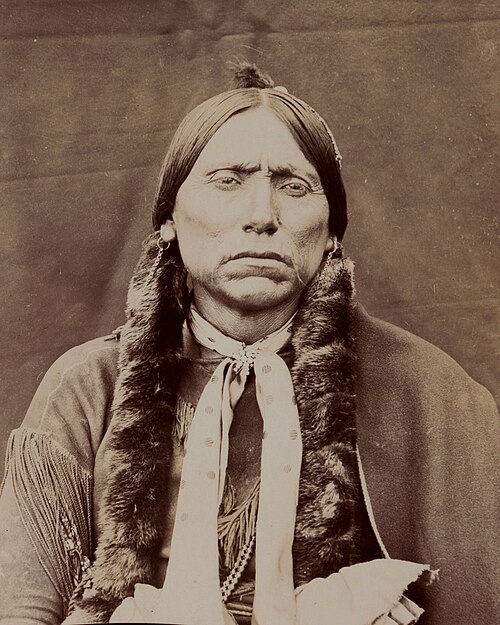

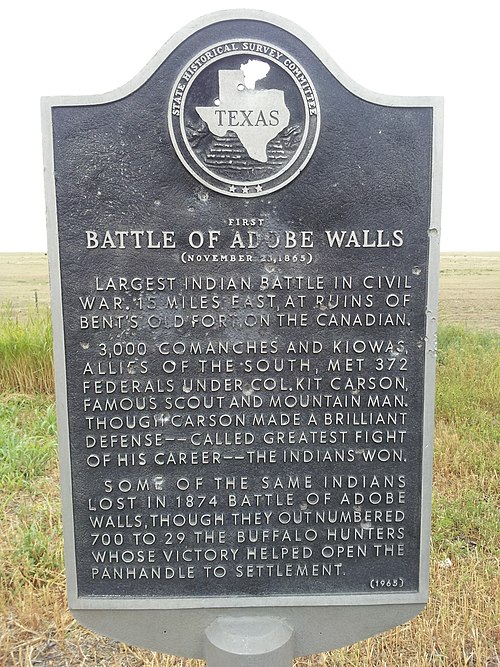

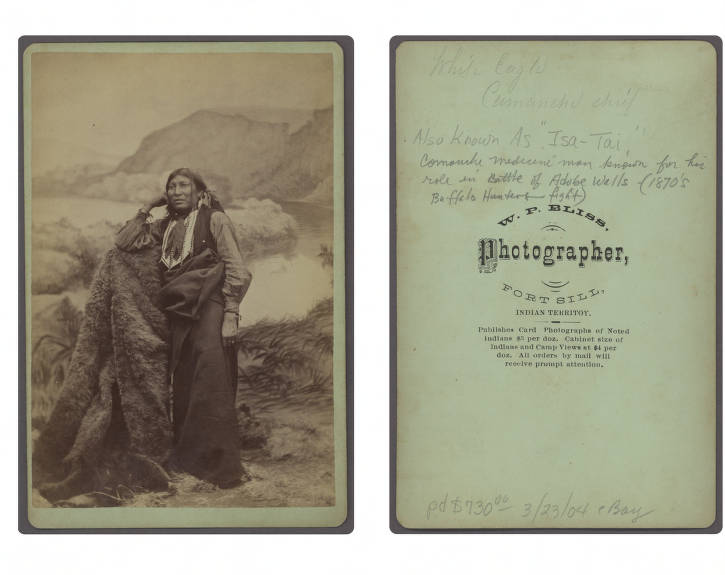

In the summer of 1874, tensions between the Plains Indians and the buffalo hunters erupted into open conflict at Adobe Walls. A coalition of Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors – angered by the destruction of the buffalo herds and urged on by a young Comanche medicine man named Isa-tai (White Eagle) – decided to attack the outpost[17][18]. On June 27, 1874, just before dawn, approximately 700 Native warriors under Comanche leader Quanah Parker launched a surprise charge on the settlement[19][18]. Inside Adobe Walls were only 28 men and one woman, most of them seasoned buffalo hunters armed with powerful “Big Fifty” Sharps rifles. The initial onslaught at daybreak was ferocious: the warriors galloped in with rifles blazing and lances ready, letting out war whoops that, as Dixon later recalled, “seemed to shake the very air of the early morning”[20]. The hunters, many half-dressed from being jolted out of sleep, quickly barricaded themselves in the two stores and Jim Hanrahan’s saloon to make their stand[21][22]. Dixon himself sprinted to Hanrahan’s saloon under gunfire, joining a small group that notably included 20-year-old Bat Masterson, who would later become a famed lawman[23][24]. From inside these adobe buildings, the defenders poured steady rifle fire into the charging warriors. They repelled the first attack with surprisingly few losses – only two defenders were killed in the initial charge, while the attackers took significant casualties from the hunters’ long-range Sharps rifles[25]. Bat Masterson later praised Billy Dixon’s cool bravery during those frantic first minutes of battle. Dixon had been firing from a window alongside him, and Masterson recalled that Billy was “a remarkable man, always cool, a dead shot no matter what the distance, never saying a word, always alert”[26]. Such steady nerves and expert marksmanship made a critical difference in withstanding the overwhelming assault.

After the failure of their dawn charge, the native forces settled into a loose siege, sniping from cover and periodically probing the post over the next several days[27]. The defenders hunkered down, and sporadic exchanges continued. On the second day of the standoff, June 28, the conflict entered legend. A group of about fifteen to twenty Cheyenne warriors gathered on a high mesa or ridge nearly a mile from the trading post – perhaps out of the effective range of the hunters’ rifles, they thought[28]. By this point, Billy Dixon had earned respect as the best shot in the camp, so his companions urged him to try a long-range shot to scatter the distant observers[29][30]. Dixon borrowed a .50-90 Sharps buffalo rifle (a heavier-caliber gun than his own) from Hanrahan’s saloon and took careful aim at the distant riders[31]. Firing from inside the stockade, he judged the range, adjusted the peep sight for maximum elevation, and squeezed off a shot. The first attempt fell short; working the single-shot Sharps, he tried again, perhaps a third time.[32][33] Finally, against astounding odds, a warrior toppled from his horse far in the distance. Several seconds later, the sound of Dixon’s rifle report reached the ridge – confirming to the Indians that the impossible had happened[34][35]. Dixon’s bullet had struck a mounted Comanche warrior (identified in some accounts as a man named Tohahkah) from an estimated 1,538 yards away[36][37]. This incredible shot – approximately 7/8 of a mile – killed or wounded the warrior (reports differ), and utterly demoralized the besieging natives[28][38]. Stunned that even at such a distance they were not safe from the hunters’ big rifles, the allied tribes soon decided to withdraw. The siege of Adobe Walls was effectively broken by that single long-distance hit, later famously known as “The Shot of the Century”[36].

Billy Dixon himself never romanticized his famous shot, humbly calling it a “scratch shot” – a lucky hit that he doubted he could repeat[39]. Nonetheless, its effect was significant. Within a few days, as more armed frontiersmen arrived to reinforce the post, the Indian war party abandoned the fight and dispersed[40]. The Second Battle of Adobe Walls, though a small fight in terms of numbers, proved to be a turning point in the Southern Plains. The natives’ failure to defeat the buffalo hunters shattered the prophecy of invulnerability given by Isa-tai and dealt a spiritual blow to the tribes’ morale[35]. In the aftermath, the U.S. Army launched the Red River War of 1874–1875, a concerted campaign to subdue the Plains tribes once and for all[41]. The battle at Adobe Walls thus “marked the beginning of the Red River War, and changed the landscape of America forever,” as one historian noted[42]. By the end of that war, the Comanche, Kiowa, and Cheyenne were forced onto reservations in Indian Territory, and the era of free-roaming buffalo herds and Plains Indian dominance was effectively over[41][43]. Billy Dixon’s role in the fight – especially his legendary long shot – became the stuff of frontier lore and cemented his status as the “Hero of Adobe Walls”[44].

U.S. Army Scout and the Buffalo Wallow Fight

The Adobe Walls battle also marked the end of Billy Dixon’s career as a commercial buffalo hunter. Mere weeks after the fight, he accepted an appointment as an Army scout. In early August 1874 at Fort Dodge, General Nelson A. Miles enlisted Dixon as a scout for the U.S. Army, which was preparing to move against the hostiles in the Texas Panhandle[45]. Dixon’s knowledge of the terrain and experience with Indian warfare made him an invaluable asset. The Army did not have to wait long to test his mettle. On September 12, 1874, Dixon and another famed scout, Amos Chapman, were carrying dispatches for Miles’s command along with four cavalry troopers (Sergeant Zachariah T. Woodall and Privates Peter Roth, John Harrington, and George Smith)[46]. At sunrise on the open plains near the Washita River (close to Gageby Creek in present-day Hemphill County, Texas), the six-man detail was ambushed and surrounded by a large combined war party of Comanche and Kiowa warriors[47]. The scouts and soldiers quickly took cover in a shallow buffalo wallow – a natural depression – and a fierce fight ensued, later known as the Battle of Buffalo Wallow (or the fight at Buffalo Wallow).

Outnumbered by dozens of mounted warriors, Dixon and his comrades held off repeated attacks throughout the day. Using their horses’ carcasses and the rim of the hollow for cover, the little group managed to kill and wound several attackers, but all of the defenders were hit by gunfire in the process[48]. Billy Dixon himself sustained a painful leg wound. One trooper, Private Smith, was killed, and by nightfall the situation was dire – the survivors were badly injured and nearly out of water. That night, a cold rain storm blew in on the plains, which proved a godsend: the rain discouraged the besieging warriors, who broke off the fight and disappeared by morning[48]. After enduring about 36 hours in the wallow, Dixon and the remaining men were rescued by an Army relief column. The fight had been a desperate ordeal, and the courage shown there did not go unrecognized. All five surviving defenders of the Buffalo Wallow fight, including civilian scouts Billy Dixon and Amos Chapman, were awarded the Medal of Honor by Congress for their heroism[49]. Dixon was one of only a handful of civilians to have ever received the Medal of Honor in U.S. history.[50] (He technically served as a civilian scout, as did Chapman, in Miles’s employ. Decades later, in 1916, the Army rescinded many medals given to civilian scouts, but those of Dixon and Chapman were eventually reinstated, ensuring his name remains on the honor roll of Medal of Honor recipients for the Indian Wars[50].)

Dixon continued to serve as a scout through the remainder of the Red River War. Just two months after the wallow fight, in November 1874, he participated in the rescue of the German (Germain) sisters, young siblings who had been captured by Cheyenne warriors during a raid in Kansas earlier that year[51]. Dixon was with the detachment that discovered and liberated two of the girls on November 8, 1874, along McClellan Creek – a moment of relief amid a grim campaign. He also took part in other notable expeditions: in spring 1875, Dixon accompanied Army engineers in selecting a site for a new fort (Fort Elliott) in the Texas Panhandle[52]. In August 1877, he was attached as a guide to Captain Nicholas Nolan’s ill-fated expedition pursuing Comanche stragglers in the Staked Plains (Llano Estacado). During that expedition, Dixon’s expertise likely saved the unit; when the soldiers became lost and desperate for water, Dixon guided them to a water source at Double Lakes, avoiding disaster in the arid plains[52]. After years of such rugged service, Billy Dixon decided to leave the Army. In 1883, at age 33, he returned to civilian life as the frontier itself was rapidly changing.

Later Life and Death

After returning to civilian life, Dixon remained in the Texas Panhandle, a region he had helped open to settlement. He worked for a time on the Turkey Track Ranch, one of the large cattle ranches in the area. [53] Ever entrepreneurial, he then built a log home near the old Adobe Walls site – essentially returning to the very spot where he had gained fame in 1874. There he staked out a small ranch, planted a fruit orchard and 30 acres of alfalfa, pioneering irrigated farming in that part of the Panhandle[54]. In August 1887, when a U.S. post office was established at the remote Adobe Walls locale, Dixon was appointed the first postmaster—a position he would hold for two decades.[55] Settling into the role of community leader, he also served as a justice of the peace and as a land commissioner for the region surrounding Hutchinson and neighboring counties.[56][57] Together with a partner, S. G. Carter, he ran a small ranch supply store out of his home, catering to local cowboys and settlers[58]. Though far removed from his buffalo-hunting days, Dixon was a respected pioneer of the Panhandle frontier during this period.

On October 18, 1894, Billy Dixon married Olive King, a schoolteacher from Virginia[59]. Olive joined him at his isolated homestead, becoming (as she later noted wryly) the only woman living in Hutchinson County for about three years[60]. The couple started a family and would eventually have seven children[60]. As the new century dawned, the Dixons moved briefly to the small town of Plemons, Texas, in 1902 so that their children could attend school[61]. Ever restless in town life, Billy decided in 1906 to relocate once more to open country – this time homesteading in the Oklahoma Panhandle, near the Cimarron County line[62]. He was in his late 50s by then, and the rough life of the frontier had taken its toll on his health and fortunes. In his final years, Dixon’s finances were meager; he reportedly lived near poverty, and friends petitioned the government to grant him a pension for his Army scouting service (an effort that saw little success)[63].

Billy Dixon’s grave at the Adobe Walls battlefield site. He died in 1913 and was originally buried in Texline, Texas. However, in 1929, his remains were reinterred at this spot, marked by a granite tombstone, to honor his role in the historic 1874 fight. [64]

On March 9, 1913, William “Billy” Dixon died of pneumonia at his homestead in Cimarron County, Oklahoma[65]. He was 62 years old. Members of his Masonic Lodge traveled to give him a proper burial in the town cemetery in Texline, Texas, just across the state line.[66] However, his wife, Olive, was determined that Billy’s legacy not be forgotten. In 1929, she arranged for his remains to be reinterred at Adobe Walls, the site of his most famous battle[67]. On June 27, 1929 – exactly 55 years after the battle – Billy Dixon’s coffin was laid to rest on the windswept plains of Adobe Walls, where a red granite monument now marks his grave beside the graves of other hunters[67]. Fittingly, he sleeps where his legend was made.

Legacy and Impact

Billy Dixon’s life bridged the era of the wild buffalo frontier and the settled plains that followed, and his legacy looms large in the lore of the American West. He is remembered foremost for his extraordinary marksmanship and courage under fire. The long-distance rifle shot he made at Adobe Walls became one of the most storied feats in Western history – frequently cited as one of the longest recorded sniper kills of the 19th century and immortalized as the “Shot of the Century” by later historians[36]. That single bullet’s impact went beyond the tactical realm; it carried symbolic weight, signaling that even the great warriors of the Plains were no match for the range and power of frontier rifles. Dixon’s sharpshooting exploits, coupled with his coolness in combat, made him a legend in dime novels and historical accounts alike. (It was said that no distance was too great for Dixon’s steady hand – an assessment seconded by Bat Masterson and others who knew him[26].) Yet, Dixon himself remained modest about his abilities, attributing his famous shot to luck and often preferring to credit his comrades for their collective defense[39][68].

Beyond his marksmanship, Dixon’s legacy is tied to significant chapters of frontier history. He was directly involved in events that hastened the end of the Plains Indians’ freedom – the Adobe Walls fight and the ensuing Red River War – and he received the Medal of Honor for bravery during those Indian Wars.[49] As a civilian scout-turned-homesteader, his life story illustrates the transformation of the West: from the vast buffalo ranges of his youth to the fenced ranches and farms of his later years. In recognition of his contributions, various landmarks bear Dixon’s name. Dixon Creek in Hutchinson County, Texas, is named in his honor, and a Billy Dixon Masonic Lodge in Fritch, Texas, also commemorates him[69]. His personal artifacts and Sharps rifle are preserved in Panhandle museums, keeping his memory alive[67].

Much of what we know about Billy Dixon today comes from his own recollections, which he narrated shortly before his death. Olive King Dixon, his devoted wife, transcribed and published these memoirs in 1914 as “Life and Adventures of ‘Billy’ Dixon.” Olive went on to spend 43 years after Billy’s passing tirelessly promoting and preserving his story[37]. She successfully lobbied for historical markers and recounted his deeds to generations of Texans, ensuring that her husband’s name would always be associated with frontier valor[37]. Thanks to her efforts, Billy Dixon’s grave at Adobe Walls became a hallowed spot, and the tale of his legendary shot remains a highlight of Old West history. In the broader scope of American frontier lore, Billy Dixon stands alongside the likes of Buffalo Bill Cody and Davy Crockett – a figure who embodies the grit, marksmanship, and adventurous spirit of the Wild West. His life’s story, from orphaned farm boy to famed scout and rifleman, is a vivid reminder of the challenges and changes that defined the late 19th-century frontier[44]. Over a century later, Billy Dixon’s legacy endures as both a historical reality and a cornerstone of sharpshooting legend on the American frontier.

Sources: Historical accounts and records including the Handbook of Texas Online[70][28], Billy Dixon’s own memoirs (as compiled by Olive K. Dixon)[2][5], and scholarly articles in Wild West and frontier history publications[71][36]. These sources offer detailed insights into Dixon’s life, the events of Adobe Walls, and the lasting impact of his marksmanship and frontier service on American history.

[1] [3] [6] [7] [8] [11] [12] [45] [49] [51] [52] [53] [56] [58] [59] [60] [64] [65] [66] [67] [69] [70] Dixon, William

https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/dixon-william

[2] [4] [5] Life and Adventures of “Billy” Dixon of Adobe Walls, Texas Panhandle, Compiled by Frederick S. Barde —A Project Gutenberg eBook

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/45075/45075-h/45075-h.htm

[9] [10] [14] [18] [47] [48] [54] [55] [57] [61] [62] [63] Billy Dixon – Texas Plains Pioneer – Legends of America

[13] [15] [16] [22] [23] [24] [26] [42] [68] The Second Battle of Adobe Walls – Panhandle Masonic Cowboy Hall Of Fame Association

[17] [29] [30] [33] [34] [35] [36] [38] [43] The Shot of the Century: How Billy Dixon Changed History with a Bullet

[19] [21] [25] [27] [28] [40] [41] Adobe Walls, Second Battle of

https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/adobe-walls-second-battle-of

[20] [32] [37] [44] [71] Sharpshooter Billy Dixon Owes His Legacy to His Widow