Introduction

From ancient catacombs to televised crusades, the history of Pentecostalism is a story of spiritual fervor that refuses to be extinguished. Born from a longing for more than ritual or doctrine, Pentecostalism reflects a persistent hunger for a living, direct encounter with the divine. Throughout the ages, believers have yearned for God’s presence, and time and again, their cries have been answered with manifestations such as speaking in tongues, visions, healings, and an inexpressible joy. This account examines Pentecostalism not as a sudden or isolated movement, but as part of a long-standing tradition of spiritual renewal in which the extraordinary continually presses into the ordinary.

Pre-1900 Pentecostalism

The origins of the Pentecostal movement are rooted in the New Testament account of the Day of Pentecost, as described in Acts 2:1-4. On this day, which took place fifty days after Jesus’ resurrection, the disciples were gathered together in one place when a sound like a rushing mighty wind filled the room, and what appeared to be tongues of fire rested on each of them. They were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit spoke through them. This miraculous event marked the fulfillment of Jesus’ promise that His followers would be empowered by the Holy Spirit. It is considered the birth of the early Church and serves as the foundational moment for Pentecostalism, which emphasizes Spirit baptism, speaking in tongues, and the active presence of the Holy Spirit in the lives of believers.

Throughout Christian history, episodes of intense spiritual experience bear a striking similarity to Pentecostal practices. The Apostle Paul’s letters, especially in 1 Corinthians 12–14, describe spiritual gifts such as glossolalia (speaking in tongues), prophecy, and healing. Early church fathers occasionally referenced such manifestations, though institutional Christianity gradually shifted toward structured liturgy. Nonetheless, charismatic expressions persisted, as seen in movements like the 2nd-century Montanists, who emphasized prophecy and divine ecstasy. Though later condemned as heretical, the Montanists reveal that early Christians wrestled with the same spiritual gifts later championed by Pentecostals.

During the medieval and early modern eras, spiritual encounters continued to thrive, often beyond the reach of ecclesiastical authority. Visionary mystics like Hildegard of Bingen, Catherine of Siena, and Teresa of Ávila recounted vivid experiences with God, marked by weeping, trembling, and ecstatic stillness. The revivalist movements of the 17th and 18th centuries, led by figures such as George Whitefield and John Wesley, witnessed worshippers overcome with emotion—falling, shouting, or weeping in response to conviction. Similarly, during the Great Awakenings in America, revival meetings often featured behaviors such as dancing, crying, and speaking in unintelligible tongues. These recurring manifestations underscore a continuity of Spirit-led experiences across diverse Christian landscapes.

19th and 20th Centuries

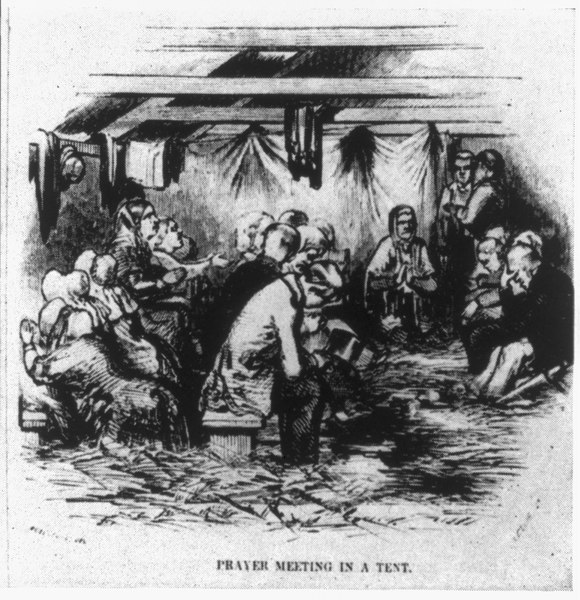

In the 19th century, revivalist events such as the Cane Ridge Revival and Holiness camp meetings were characterized by intense emotional and physical expressions of faith. Shouting, dancing, and being “slain in the Spirit” became common. These encounters laid a cultural and theological foundation for the Pentecostal revival that would erupt in the early 20th century. While Pentecostalism formalized these expressions within a theological framework that emphasizes Spirit baptism and spiritual gifts, it essentially inherited centuries of Christian embodiment of divine encounter.

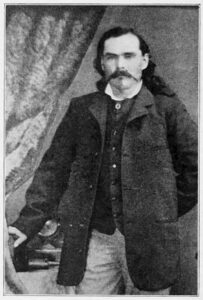

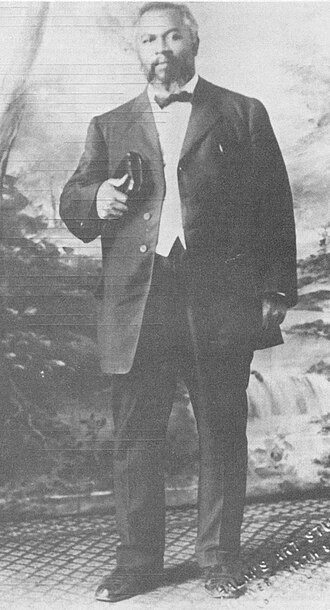

The Pentecostal movement formally took root in the early 1900s, particularly in the United States. At Bethel Bible School in Topeka, Kansas, evangelist Charles Fox Parham and his students sought to restore the spiritual power found in the Book of Acts. On January 1, 1901, a student named Agnes Ozman reportedly spoke in tongues following prayer, which Pentecostals identified as evidence of Holy Spirit baptism, akin to the account in Acts 2. This event catalyzed the movement, which gained rapid momentum and reached a climactic moment with the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles (1906–1909), led by William J. Seymour. These services featured interracial worship, prophecy, healing, and widespread speaking in tongues—hallmarks of what Pentecostals believed to be a divinely inspired return to the early church.

Baptized in The Holy Ghost

Pentecostal theology centers on the belief that their experiences fulfill biblical prophecy and New Testament promises. A key scriptural foundation is Joel 2:28–29, which speaks of God pouring out His Spirit in the last days, resulting in visions and prophecy. Pentecostals believe this prophecy began its fulfillment in Acts 2 and continues today. The quintessential belief for most Pentecostals is the transformative experience known as the Baptism in the Holy Spirit. Speaking in tongues functions as the initial outward, public evidence of this Spirit baptism. At the time of Spirit baptism, believers receive a spiritual “prayer language”. They are encouraged to engage regularly in what is known as “praying in the Spirit,” or “praying in tongues,” a practice in which the Holy Spirit intercedes through them, speaking in these unknown tongues, aligning their will with God’s will. The movement encourages the active presence of spiritual gifts, such as healing and prophecy, interpreting them as tangible signs of God’s ongoing work.

Equally central to early Pentecostal belief was the conviction that Spirit baptism empowered believers to live transformed lives marked by holiness, victory over sin, and evangelistic boldness. For early leaders like Charles Parham and William Seymour, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit was not solely about ecstatic worship or visible gifts, but about becoming more Christlike in character and mission. They taught that the baptism in the Holy Spirit was a divine empowerment for daily living—producing purity, humility, love, and moral integrity in the life of the believer.

This moral and ethical dimension of Spirit baptism distinguished early Pentecostalism from emotional revivalism alone. The Spirit was understood to both sanctify and energize. Holiness was not merely a theological term, but a lived expectation. Pentecostals believed that the same Spirit who enabled tongues and healing also called them to integrity, compassion, and a life surrendered to God’s purposes. The infilling of the Spirit was viewed as essential for bold witness, spiritual discernment, and power to fulfill the Great Commission—not just for personal edification, but for world-changing mission.

By connecting Old Testament promises with the New Testament outpouring of the Spirit, Pentecostals frame their movement as a continuation—not an innovation—of authentic Christianity. They regard Pentecostalism as a recovery of the Spirit-empowered life found in scripture, one that has echoed throughout church history in various revivals and renewals. This perspective grants Pentecostals a unique identity: not a sect, but a restorationist movement with eschatological urgency and missionary zeal.

The Age of Radio and Television

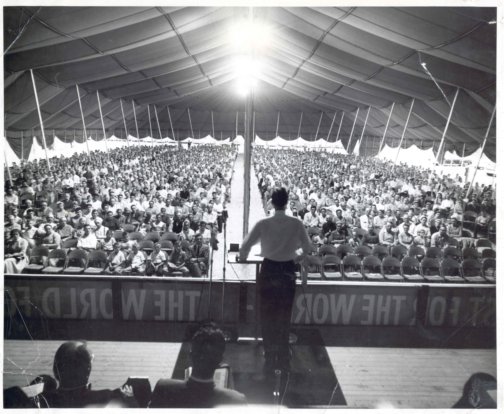

The 1950s witnessed the rise of healing evangelists such as Oral Roberts, A.A. Allen, Jack Coe, and William Branham, who helped transition Pentecostalism into the mainstream. Emerging from post–World War II revivalism, these faith healers conducted massive tent crusades that emphasized divine healing and miracles. Their use of radio and television expanded Pentecostalism’s reach and introduced themes of personal prosperity and supernatural intervention to broader audiences. These campaigns helped reframe Pentecostalism from a fringe movement to a significant influence in American religious life.

The tent revival era reshaped Pentecostalism in several important ways. First, it loosened denominational boundaries. Many evangelists operated independently or had strained relationships with major Pentecostal denominations, such as the Assemblies of God or the Church of God in Christ. Second, these revivals introduced Pentecostal practices to non-Pentecostal Christians, thus setting the stage for the later Charismatic Renewal within mainline Protestant and Catholic circles. In this way, the healing evangelists bridged the gap between classical Pentecostalism and the expanding Charismatic movement.

Theologically, these revivals laid the groundwork for the Word of Faith movement, which teaches that faith can bring about healing and material blessing. This would develop into the prosperity gospel—a theology influential in many contemporary Charismatic and Neo-Pentecostal contexts. Consequently, the 1950s healing revivals played a pivotal role in expanding Pentecostalism’s public presence, shaping its theology, and modernizing its outreach.

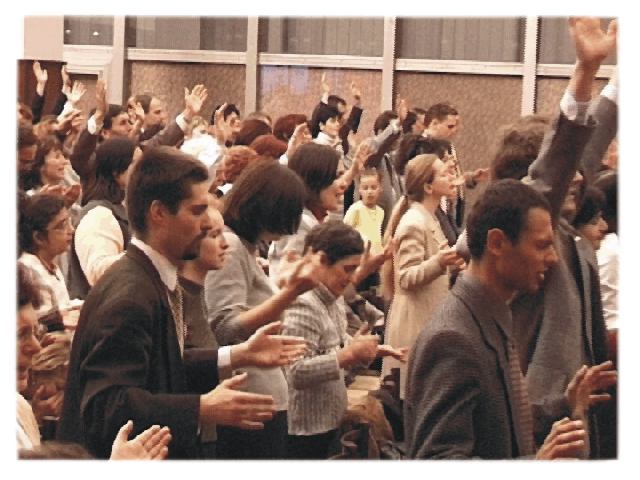

Charismatic Renewal

Following the 1970s, Pentecostal and Charismatic expressions underwent significant diversification. The Charismatic Renewal introduced Spirit-empowered worship and gifts into Catholic and mainline Protestant churches while maintaining traditional liturgies. Classical Pentecostal denominations continued to grow institutionally, establishing Bible colleges and mission agencies. The 1980s and 1990s witnessed the rise of televangelism and Word of Faith ministries, led by figures such as Kenneth Hagin, Benny Hinn, and T.D. Jakes. Jakes. These ministries fused charismatic spirituality with media outreach and motivational teaching, further expanding Pentecostal influence.

As the movement entered the 21st century, many Pentecostals embraced non-denominational models, digital media, and global networks. Churches like Hillsong and Bethel popularized worship music, prophetic ministry, and supernatural experiences. This shift blurred distinctions between Pentecostal and Charismatic traditions, placing less emphasis on doctrinal boundaries and more on experiential faith. While global Pentecostalism thrived in Africa, Latin America, and Asia, Western expressions often became post-denominational and culturally adaptive. Theological diversity grew, with some churches preserving holiness traditions and others pursuing innovative, therapeutic ministry styles.

In contemporary settings, Pentecostals and Charismatics span a wide spectrum. In urban churches, especially, worship styles and theological emphases often overlap across traditions. While classical Pentecostal denominations maintain distinct teachings, such as the initial evidence of tongues, many independent Charismatic churches focus on prophecy, healing, and deliverance without strict doctrinal requirements. Despite differences, a shared commitment to the Holy Spirit’s transformative power, evangelism, and global mission unites these communities. Compared to their early 20th-century beginnings marked by poverty and racial integration, today’s Pentecostals often minister within affluent, multicultural, and technologically advanced contexts.

Criticism and Persecution

The transition from classical Pentecostalism to the Charismatic movement also brought key differences in ethos and practice. Early Pentecostals often adopted a separatist identity, emphasizing holiness, simplicity, and visible signs, such as speaking in tongues (glossolalia). Charismatics, however, sought renewal within existing churches and tended to de-emphasize separation, favoring integration and varied expressions of Spirit empowerment. This contrast sometimes led to friction—Pentecostals viewed Charismatics as compromising, while Charismatics saw Pentecostals as inflexible. Although both valued the Holy Spirit’s activity, their differing ecclesiologies created enduring distinctions.

Criticism and opposition to Pentecostalism have arisen both from within the church and from secular institutions. Theologically, many Protestants and Catholics have challenged Pentecostal practices, particularly “speaking in tongues”. Cessationist theologians argue that miraculous gifts ended with the apostolic age, labeling contemporary experiences as emotionalism or misinterpretation. The prosperity gospel, which claims God wants all Christians to be wealthy, has also faced significant criticism for allegedly exploiting the vulnerable and misrepresenting Christian teachings.

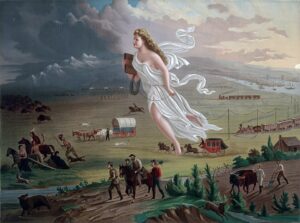

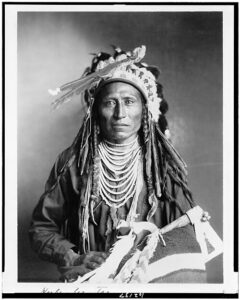

Beyond opposition and criticism, Pentecostals have frequently faced persecution. In Latin America, they clashed with dominant Catholic cultures. In parts of Asia and Africa, Pentecostals have experienced state harassment and religious hostility. Under Communist regimes—such as the former Soviet Union and modern China—unauthorized Pentecostal gatherings have resulted in imprisonment and confiscation of property. Even in early 20th-century America, Pentecostals faced ridicule due to interracial services and emotional worship styles.

Pentecostals have responded in various ways. Many have interpreted opposition as a mark of faithfulness, paralleling the persecution of the early church. Others have invested in theological education, creating seminaries and academic networks to strengthen doctrinal integrity. Pentecostals often cite global growth and transformed lives as validation of their beliefs, emphasizing personal testimony and divine encounters over polemical debate. As one of the fastest-growing Christian movements worldwide, Pentecostalism has proven resilient in the face of criticism.

The Future of Pentecostals

While the defining doctrine of the Pentecostal movement has historically centered on the baptism in the Holy Spirit—evidenced by speaking in tongues and accompanied by various manifestations of the Spirit in public worship—many modern Pentecostals have quietly distanced themselves from these beliefs. Though few openly disavow the doctrine, some pastors and leaders within trinitarian Pentecostal denominations no longer preach or teach evidential tongues, often citing a desire to appeal to seekers who might be uncomfortable with such expressions. Privately, some admit they no longer believe in the traditional teaching of initial physical evidence or in many of the Spirit manifestations once widely embraced. Some no longer believe in the baptism in the Holy Spirit. This theological shift has been further influenced by the growing presence of non-Pentecostal academic influence within Pentecostal leadership, leading many churches—especially large, urban congregations—to move away from a distinctively Pentecostal identity and toward a more generic evangelical expression. As a result, it is increasingly difficult to distinguish whether a given church is Pentecostal, Baptist, or Methodist. Some have gone so far as to conceal any Pentecostal denominational affiliation within literature or signage.

One notable exception remains the Pentecostal Holiness and Oneness (or “Jesus’ Name”) movements, which continue to be vocally committed to classical Pentecostal doctrines and maintain distinctive outward standards, including a very distinct dress code.

Yet even as Pentecostalism undergoes another period of transition—much like the shifts seen in the 1950s and 1970s—the current movement appears to be drifting further away from its historic trademarks, moving toward expressions of faith that are less aligned with traditional Pentecostal distinctives.

Conclusion

Today, over 600 million Pentecostals and Charismatics form a dynamic and diverse global movement. Representing a wide range of cultures and denominations, they remain unified by a shared experience of the Holy Spirit’s power. While some align with established denominations, such as the Assemblies of God, others gather in independent or informal settings. Their worship blends contemporary music, digital engagement, and mass events. Educational institutions, mission organizations, and media ministries now support the movement, which has undergone significant evolution since its early days.

From whispered prayers in secluded rooms to stadiums filled with praise and streamed worship services, Pentecostalism has continually adapted while remaining rooted in biblical tradition. It began as a marginalized movement, yet today it has a profound influence on global Christianity in theology, worship, and social practice. While some abandon the bedrock biblical principles that have defined the movement, Pentecostals look to the future with confidence that the Holy Spirit will continue to empower, guide, and transform lives through Spirit Baptism and the manifestation of God’s Presence in every facet of life.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Allan. An Introduction to Pentecostalism: Global Charismatic Christianity. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Burgess, Stanley M., and Eduard M. van der Maas, eds. The New International Dictionary of Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements. Zondervan, 2002.

- Hollenweger, Walter J. Pentecostalism: Origins and Developments Worldwide. Hendrickson Publishers, 1997.

- Synan, Vinson. The Holiness-Pentecostal Tradition: Charismatic Movements in the Twentieth Century. Eerdmans, 1997.

- Robeck, Cecil M. The Azusa Street Mission and Revival: The Birth of the Global Pentecostal Movement. Thomas Nelson, 2006.

- Cartledge, Mark J. Pentecostal Theology: A Theology of Encounter. T&T Clark, 2010.

- Kay, William K. Pentecostalism. SCM Press, 2009.

- Miller, Donald E., and Tetsunao Yamamori. Global Pentecostalism: The New Face of Christian Social Engagement. University of California Press, 2007.

- Macchia, Frank D. Baptized in the Spirit: A Global Pentecostal Theology. Zondervan Academic, 2006.

- Alexander, Estrelda Y. Black Fire: One Hundred Years of African American Pentecostalism. InterVarsity Press, 2011.