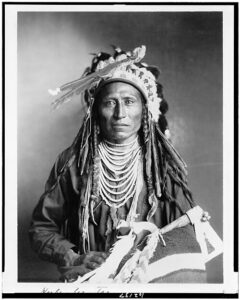

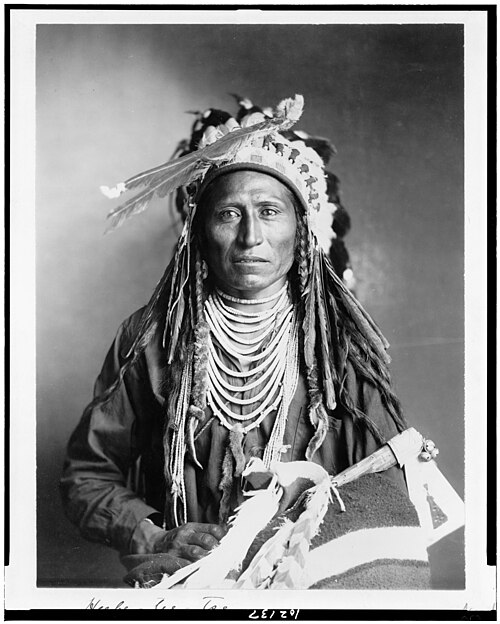

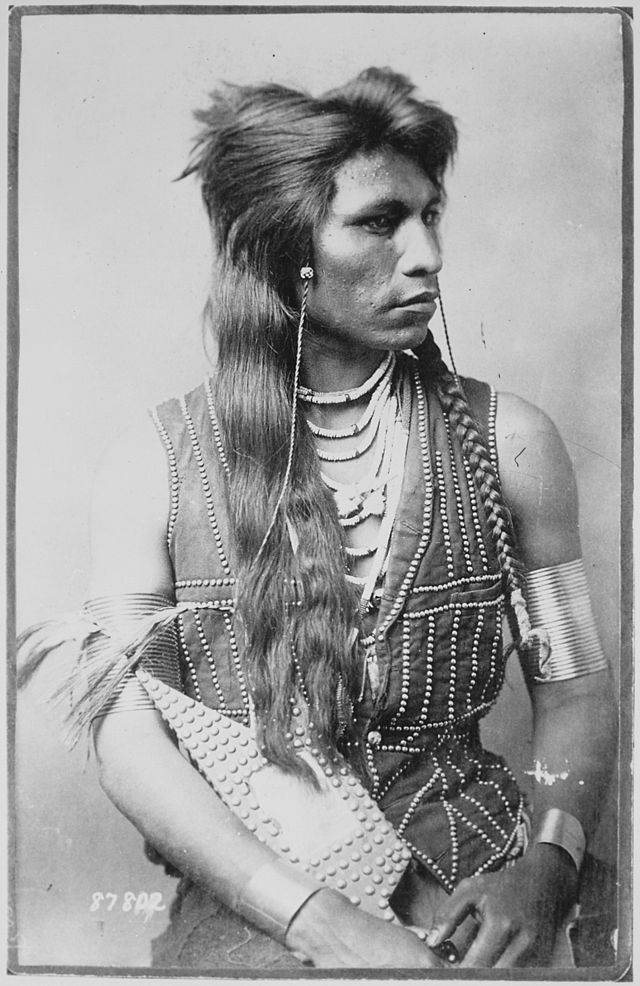

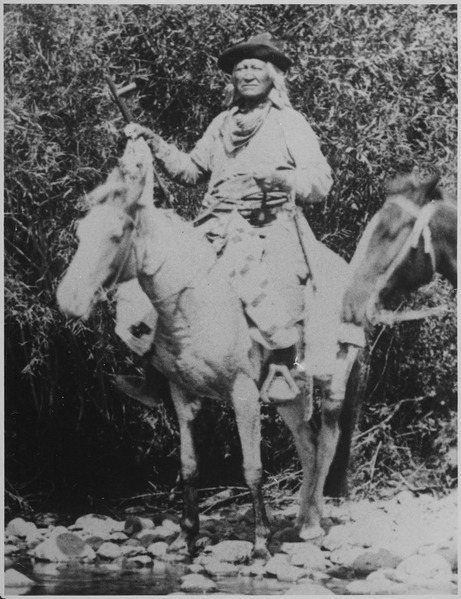

Heebe-tee-tse, Shoshone Indian,

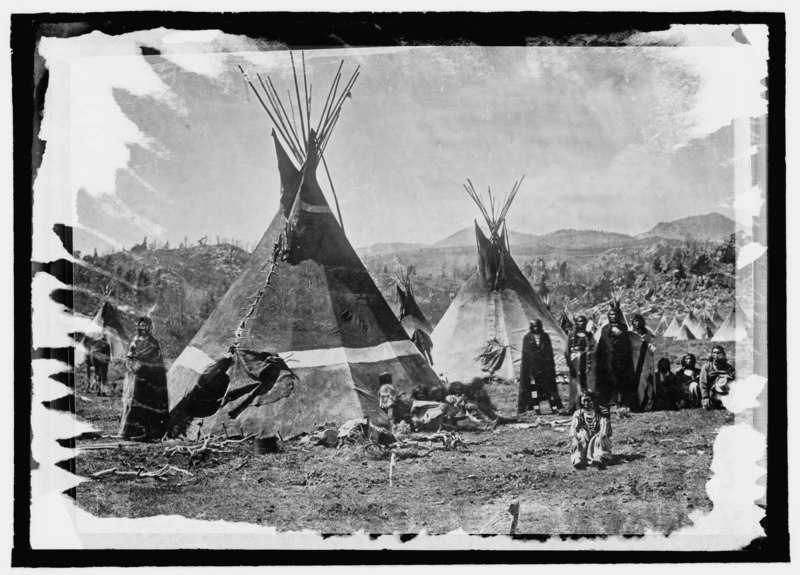

The story of the Shoshone people begins long before written records. Linguists and archaeologists trace their origins to the Uto-Aztecan language family, which connects them to peoples as far south as central Mexico. Around A.D. 1000 to 1200, their ancestors moved into the Great Basin, bringing with them a tradition of survival in harsh landscapes. They lived in small, mobile groups, gathering roots, seeds, and pine nuts, and hunting small animals. Over time, their bands spread into Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, and Colorado, creating distinct groups shaped by the environments they lived in.

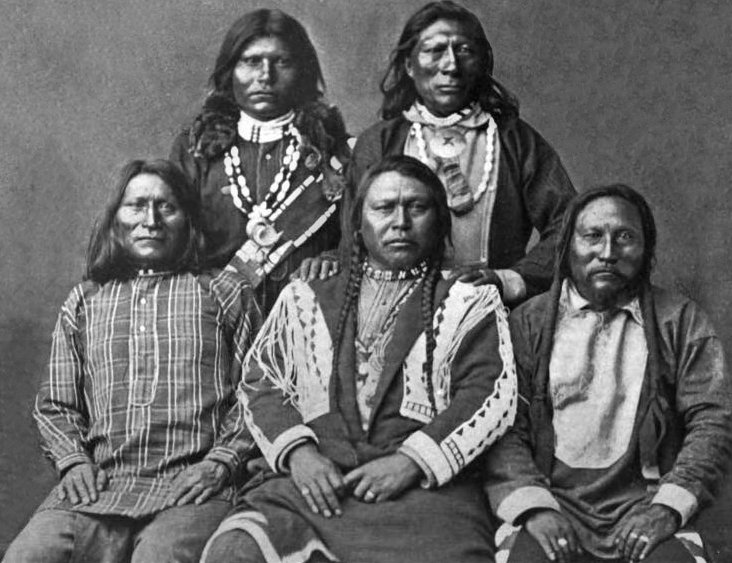

What makes the Shoshone stand out is their ability to thrive in two very different worlds. The Western Shoshone remained desert dwellers, relying on pine nuts, rabbits, and roots to survive in the Great Basin. The Eastern Shoshone, on the other hand, became powerful horsemen and buffalo hunters on the Great Plains. Few other tribes balanced life between desert subsistence and Plains warfare so successfully. Their early access to horses in the late 1600s gave them an edge over their neighbors. In fact, one of the most powerful tribes of the Plains, the Comanche, broke away from the Shoshone after acquiring horses and developed their own identity.

In the West, the pine nut harvest was not simply a food supply—it was a cultural foundation. Families returned to the same pinyon groves year after year, building traditions of stewardship that connected them deeply to the land. In the East, horses transformed the Shoshone into fierce warriors and wide-ranging hunters. This adaptability—moving between deserts and mountains, hunting buffalo on horseback, and managing fragile desert resources—set them apart from many neighboring peoples.

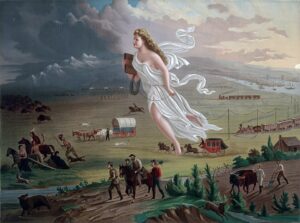

Like most tribes, the Shoshone had their share of rivals. The Blackfeet, Crow, Sioux, and Cheyenne clashed with them for control of buffalo hunting territories. In the mountains and deserts, the Ute were long-time enemies. Even the Comanche, who had once been Shoshone, fought them as they expanded across the Southern Plains. In the 1800s, the Shoshone also faced new enemies in American soldiers and settlers. The most devastating event came in 1863, when U.S. troops massacred more than 250 Shoshone men, women, and children at Bear River in Idaho.

The first Europeans the Shoshone met are difficult to pinpoint. They may have come into indirect contact with Spanish explorers in the 1600s and 1700s, but the records are vague. By the late 1700s, fur traders in the Rockies were calling them the “Snake Indians.” The first detailed descriptions came from the journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805, when the explorers met Chief Cameahwait’s band in present-day Montana. Their interpreter, Sacagawea, was a Shoshone woman who had been captured as a child and later joined the expedition. Through her, Lewis and Clark made contact with the Shoshone and secured the horses they desperately needed to cross the Rockies.

Meriwether Lewis recorded the encounter on August 13, 1805: “All the women and children of the camp were shortly collected about the lodge to indulge themselves with looking at us, we being the first white persons they had ever seen.” He added that the Shoshone chief gave them dried cakes of serviceberries and chokecherries when food was scarce. In the same entry, Lewis described Cameahwait explaining the geography of the rivers and mountains ahead, knowledge that proved vital for the expedition. These words capture a moment when two worlds—the Shoshone and the American explorers—met for the first time in direct, recorded history.

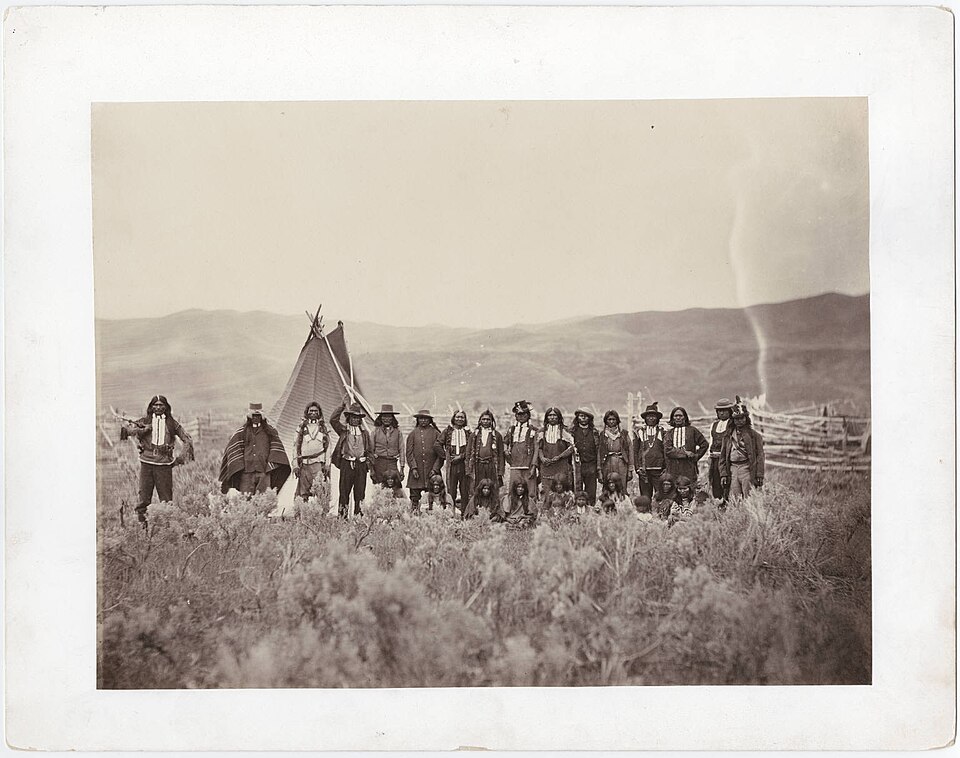

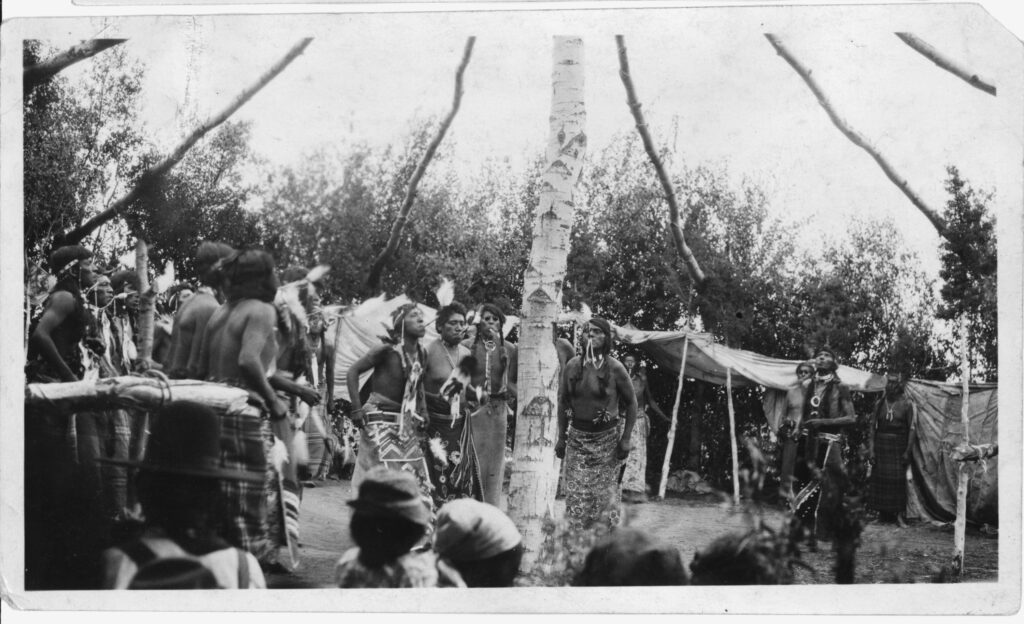

Today, the Shoshone remain a living people. Several tribes are federally recognized: the Eastern Shoshone of the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Reservation in Idaho, the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of Duck Valley on the Nevada–Idaho border, and others in Nevada such as the Te-Moak, Ely, Duckwater, and Yomba Shoshone. Their total population numbers between 12,000 and 15,000. Many Shoshone communities are working to preserve their language, pass down cultural traditions, and celebrate their history through powwows and annual pine nut harvests.

The Shoshone story is one of resilience. From their ancient migration into the Great Basin, through the challenges of enemy raids and U.S. expansion, to their enduring presence today, the Shoshone embody adaptability and strength. Their contributions, from Sacagawea’s guidance to the stewardship of their lands, remain an important part of the history of the American West.

The Shoshone are remembered not only for their survival, but for their dignity, courage, and power. They were a noble people who mastered life in both the deserts of the Great Basin and the wide-open plains, a people whose adaptability and resourcefulness reveal their strength of spirit. Despite centuries of conflict and hardship, they maintained cultural traditions that endure to this day. To honor the Shoshone is to recognize them as a proud and powerful nation whose story enriches the broader history of North America.

Bibliography

- Lewis and Clark Journals. University of Nebraska–Lincoln. https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1805-08-13

- Fowler, Catherine S. The Great Basin: Peoples and Cultures. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 1992.

- Shimkin, Demitri B. The Shoshone. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964.

- Haines, Francis. The Plains Indians: Their Origins, Migrations, and Cultural Development. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1976.

- Idaho State Historical Society. “Bear River Massacre.” Digital Collections.

- Ruby, Robert H., and Brown, John A. Indians of the Intermountain West. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981.