Introduction

In the early 19th century, the United States underwent profound economic and social changes that set the stage for the conflicts leading up to the Civil War. Americans were gripped by what one 1815 newspaper called an “almost universal ambition to get forward,” a relentless drive for commercial growth that began to remake the young nation.[1] In the decades after the American Revolution – especially following the War of 1812 – an old subsistence economy gave way to a new market-oriented economy. Rapid advances in technology and transportation, along with territorial expansion, transformed how Americans lived and worked. At the same time, the country was forced to confront the growing tension between its regions over the issue of slavery. By 1820 these trends culminated in the Market Revolution and the first major sectional compromise over slavery, the Missouri Compromise, which together form the essential context for understanding the road to the Civil War.

The Market Revolution Transforms America

After 1815, the United States experienced a “Market Revolution” – a dramatic shift from local subsistence production to a national, commercial economy. Americans eagerly embraced new technologies of the Industrial Revolution, integrating innovations like steam power to drive steamboats, mills, and eventually railroads.[2] Transportation infrastructure improved at an unprecedented pace: new roads, canals, and railroads knit together distant regions, enabling farmers, merchants, and manufacturers to exchange goods over much larger distances. Federal and state leaders actively promoted this growth – for example, Congressman Henry Clay’s celebrated “American System” called for investing in internal improvements, protective tariffs, and a national bank to foster industry and commerce.[3] In the wake of the War of 1812, President James Madison urged Congress to establish roads and canals to unite the country, and government spending on internal improvements soared.[4] The results were soon evident. By the 1820s, a “Transportation Revolution” was underway: the Erie Canal (completed 1825) linked the Great Lakes to the Atlantic, steamboats churned along the Mississippi, and the first railroads began to crisscross the eastern states.[5] Travel and communication that once took weeks now took days or hours. For example, in 1810, one traveler needed six grueling weeks to go from Connecticut to Ohio, whereas by 1829, another traveler could cross the Appalachians via the new National Road in a much shorter and more pleasant journey.[6] This burst of mobility and connectivity greatly expanded economic opportunity and bound the young nation closer together.

The Market Revolution fundamentally altered American society. More and more farmers began raising crops for profit rather than for their own subsistence, while vast factories and bustling cities emerged in the North.[7] Steam-powered textile mills in New England turned out cheap cloth, fueled by raw cotton from the South. Enormous fortunes were made in commerce and industry, and a growing middle class enjoyed new prosperity and consumer comforts. One historian famously argued that this era was nothing short of a revolution – a transformation from a rural agrarian society to a capitalist market society – that “created ourselves and most of the world we know.”[8] Yet the Market Revolution also had a darker side. Economic booms were punctuated by devastating busts (“panics”) in 1819 and 1837, which plunged many into insolvency. A lower class of property-less wage workers emerged, many laboring 13 hours a day, six days a week in mills or workshops for meager pay.[9] Wealth became more uneven: alongside new riches came new inequality. In short, as the economy advanced it pushed Americans in “new directions”, becoming “a nation of free labor and slavery, of wealth and inequality, and of endless promise and untold perils.”[10] The Market Revolution’s benefits were real – goods became cheaper, and ambitious individuals found new chances to “get forward” – but its disruptions were equally real in the form of class conflict, labor abuses, and social upheaval.[11]

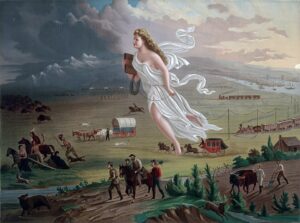

Crucially, the Market Revolution was intertwined with the expansion of slavery and growing sectional divisions between North and South. Technological changes in agriculture made slavery far more profitable at the very moment northern states were industrializing. In 1793, Eli Whitney’s cotton gin revolutionized cotton production by drastically speeding up the cleaning of cotton fibers, leading to an “agricultural explosion” in the Cotton South and a greater reliance on enslaved labor.[12] Booming British and northern textile mills hungered for Southern cotton, and planters poured into new lands in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana to establish slave plantations. Thus, even as northern states gradually abolished slavery, their factories created demand for slave-grown cotton, and northern banks and merchants helped finance the plantation economy.[13] The nation’s economy grew in complementary ways – the industrial North and the cotton-growing South were tightly linked – but this also meant the country was increasingly divided into two distinct social systems. One was a dynamic free-labor society of wageworkers, entrepreneurs, and small farmers, and the other a slave society based on forced labor and staple agriculture. The prosperity of one region often depended on the oppression of the other. As one scholar observed, northern factories “washed their hands of slavery” even as they fueled its expansion, ensuring the “continued existence of the American slave system.”[14] By the 1820s, the United States was truly a land of both freedom and bondage, a duality that would define the coming sectional crisis.

Westward Expansion and the Missouri Compromise of 1820

The early American republic had long struggled with the question of slavery’s expansion as the nation grew. Even before the Constitution was adopted, the Confederation Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, banning slavery in the vast Northwest Territory north of the Ohio River.[15] Many of the Revolutionary generation believed (or hoped) that slavery might gradually die out, and in the 1790s, new states entered the Union in a rough balance – for example, Vermont (admitted 1791) was a free state, while Kentucky (1792) came in as a slave state.[16] At the time, this parity caused little controversy. But the issue of maintaining sectional balance in Congress grew more critical with each decade, especially in the Senate, where each state had equal representation. The nation’s rapid westward expansion made the slavery question urgent. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 more than doubled U.S. territory, opening millions of new acres for settlement. [17] Meanwhile, Whitney’s cotton gin and ravenous global demand for cotton spurred a surge of plantation slavery into the Deep South after 1800.[18] Enslaved populations swelled as planters moved west, and new states formed in the Old Southwest. By 1819, the Union consisted of 22 states evenly divided between free and slave (11 each).[19] The stage was set for a showdown when the huge Missouri Territory – part of the Louisiana Purchase – sought statehood. Would Missouri allow slavery or not? On that question hung the sectional equilibrium of power.

The Missouri Crisis erupted in 1819–1820 as the first major political clash over slavery in the antebellum United States. When Missouri applied for admission to the Union, Congressman James Tallmadge of New York introduced an amendment to the statehood bill to gradually abolish slavery in Missouri (by banning new slaves and emancipating those born in the state at age 25).[20] Tallmadge’s proposal passed the northern-dominated House of Representatives but outraged Southern leaders and was blocked in the Senate. Southern congressmen reacted with “unanimous outrage,” seeing any restriction on slavery as a dangerous federal intrusion and an existential threat to their society.[21] The nation, previously complacent on the issue, suddenly “shuddered” at what one observer called an undeniable sectional controversy.[22] For the first time, Americans debated openly whether slavery’s expansion was compatible with the ideals of the republic. The debate filled newspapers and speeches; Northerners argued the Founders never intended slavery to spread, while Southerners insisted the Constitution sanctioned their right to take enslaved people into new territories.[23] The passion on each side suggested that the Union itself was at risk if a compromise could not be found.

Political compromise was achieved in 1820, defusing the immediate crisis with an arrangement engineered largely by Henry Clay – who thereby earned his nickname “the Great Compromiser.” The Missouri Compromise of 1820 contained three main provisions:[24]

- Maine (previously part of Massachusetts) would be admitted as a free state.

- Missouri would be admitted as a slave state (pairing the two kept the Senate balanced, now at 12 free vs. 12 slave states).

- In the remaining territories of the Louisiana Purchase, slavery was prohibited north of the latitude 36°30′ (Missouri’s southern boundary), except for Missouri itself. South of that line, slavery could continue to expand in future new states.[25]

This bargain maintained the sectional balance of power and alleviated tensions for the moment. When the compromise legislation passed, President James Monroe signed it into law in March 1820, and Missouri officially entered the Union as the 24th state the following year.[26] The immediate crisis subsided. One newspaper editor in 1820 noted that the geographic line dividing free and slave territories had quelled the dispute – at least for now. White Americans generally greeted the compromise with relief, believing it had settled the issue of slavery’s expansion and preserved the Union’s peace. In reality, the Missouri Compromise was a turning point and a harbinger of conflicts to come. It marked, as one historian put it, “the beginning of the prolonged sectional conflict over the extension of slavery” that would ultimately lead to the Civil War.[27] The furious debates during 1819–1820 had revealed how deeply divisive the slavery question had grown, even when cloaked in a compromise. They left, in the words of one account, “deep scars” on the body politic.[28] Americans on both sides felt that fundamental principles were at stake – even the meaning of the Declaration’s phrase “all men are created equal” was bitterly contested during the Missouri debates.[29]

Contemporary observers recognized the Missouri Compromise as a fragile truce rather than a permanent solution. Former President Thomas Jefferson, watching the storm from retirement at Monticello, was alarmed at the ominous portent of sectional division. “This momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror,” Jefferson wrote in 1820, calling the Missouri crisis “the knell of the Union” – a death knell – and warning that the issue was only “hushed… for the moment” and was “a reprieve only, not a final sentence.”[30] He feared that drawing a fixed line between slave and free territories would never be erased and would only deepen animosities over time.[31] In Jefferson’s vivid metaphor, the nation had “the wolf by the ears” – meaning slavery was a dangerous creature that Americans could neither safely hold onto nor safely let go – with justice on one side and self-preservation on the other.[32] His forebodings would prove prescient. The Missouri Compromise managed to calm the crisis of 1820 and postpone a sectional rupture for three more decades. During that time, the United States continued to expand westward, and the uneasy balance established in 1820 held on the surface. But the core question of whether new states would be slave or free continued to fester, re-emerging with even greater intensity in the 1840s and 1850s. The compromise itself was later repealed in 1854, and the sectional “fire bell” that Jefferson heard in the night finally rang out in full: the Union would indeed split apart in 1861.

Conclusion

By the 1820s, the United States stood transformed by the Market Revolution and was increasingly divided by the issue of slavery’s expansion. A booming capitalist economy had linked North and South in a web of commerce while simultaneously highlighting their very different labor systems and social orders. Westward growth forced the country to confront the moral and political contradictions between a free society and a slave society existing under one flag.

The Missouri Compromise provided a temporary political solution, balancing the interests of slave and free states, and giving Americans a false hope that compromise could always preserve the Union. In truth, it was a temporary bandage over a widening wound. The tensions and trends evident by 1820 – industrial growth and modernization in the North, plantation expansion in the South, and heated disputes over the spread of slavery – established the fundamental context for the coming years. In this course, we will see how these issues evolved and intensified, ultimately breaking the bonds of union. The Market Revolution set the economic and social stage, and the Missouri Compromise sounded the opening bell of a great national argument. Together, these developments help us define the landscape of antebellum America – a nation of progress and prosperity, but also of profound sectional discord – on the eve of the Civil War.[33]

Sources

- American Yawp, Chap. 8, “The Market Revolution” (Stanford Univ. Press, 2019), 154–61.

- Ibid., 154–61.

- Ibid., 101–07.

- Ibid., 203–12.

- Ibid., 221–30.

- Ibid., 221–30.

- Ibid., 163–70.

- Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815-1846 (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1991), 55–63.

- American Yawp, 177–85.

- Ibid., 181–89.

- Ibid., 177–85.

- Ibid., 77–84.

- Ibid., 181–89.

- Ibid., 181–89.

- Teaching American History, “Northwest Ordinance” (1787), 133–40.

- Ibid., 142–49.

- Ibid., 151–59.

- Ibid., 151–59.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, “Missouri Compromise” (2025), 271–80, 297–300.

- Ibid., 273–81.

- Teaching American History, “Missouri Compromise Debates,” 179–87.

- Ibid., 179–87.

- Ibid., 199–217.

- Ibid., 186–94.

- Ibid., 186–94.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, “Missouri Compromise,” 252–56.

- Ibid., 252–56.

- Teaching American History, “Missouri Compromise Debates,” 196–204.

- Ibid., 199–207.

- Thomas Jefferson, Letter to John Holmes, April 22, 1820, in Jefferson: Writings (Library of America, 1984), 968–76.

- Ibid., 968–76.

- Ibid., 974–81.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, “Missouri Compromise,” 252–56.