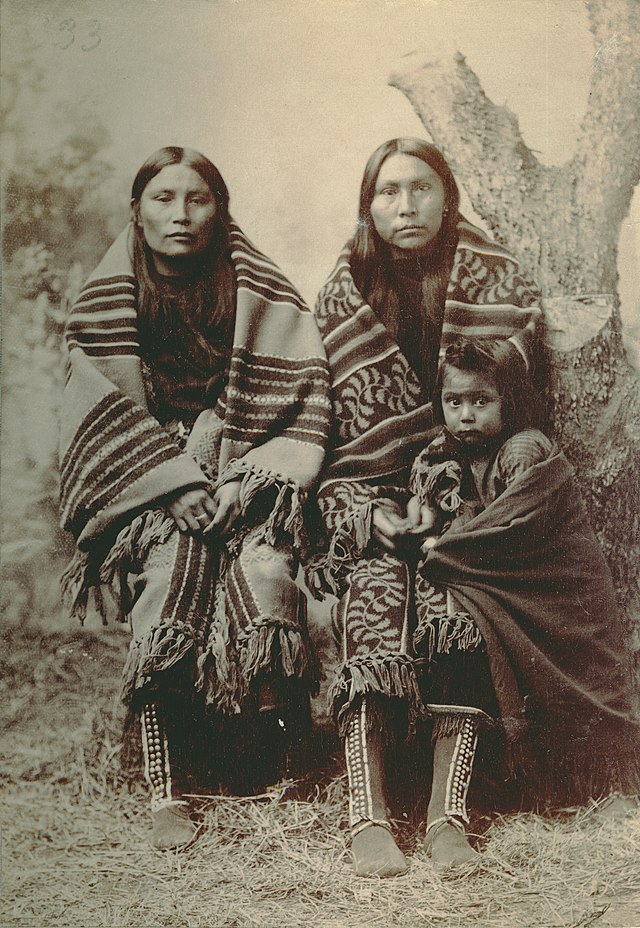

Two Comanche women and a small child.

Introduction

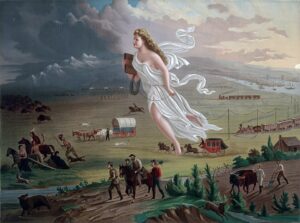

Long before fences split the plains and railroads carved through the wilderness, a fierce and free people thundered across the grasslands of what is now the American Southwest. The Comanche, born of the mountains and shaped by the wind-swept plains, rose to become one of the most powerful and influential Native American nations in North America. Their story is not merely one of warriors and horses, but of complex political systems, cultural resilience, spiritual depth, and a unique ability to adapt and dominate their environment. Emerging from the Rocky Mountains, the Comanche forged a new identity on the Southern Plains, displacing rivals, resisting colonization, and leaving an indelible mark on the history of the United States. This narrative traces their journey—from their ancient origins to their modern presence—exploring their conflicts and alliances, traditions and transformations, triumphs and tragedies. It is a story rooted in fact, drawn from the most respected historical sources, and told with a commitment to honoring the legacy of a people whose spirit still rides the winds of the West.

Origins

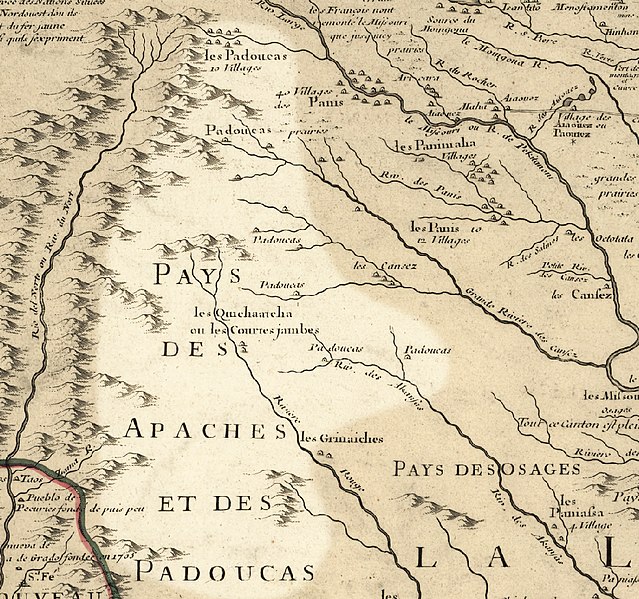

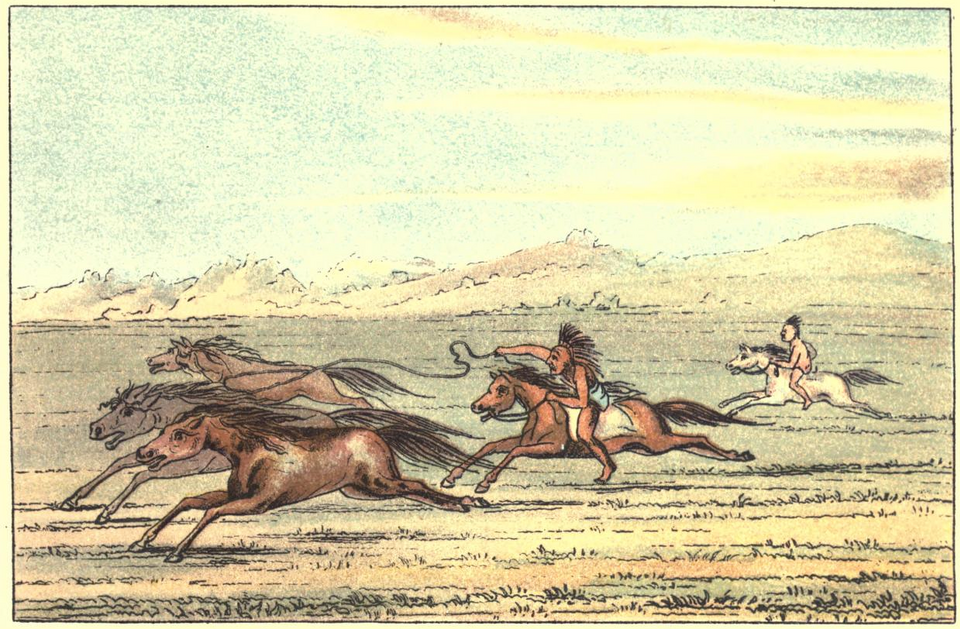

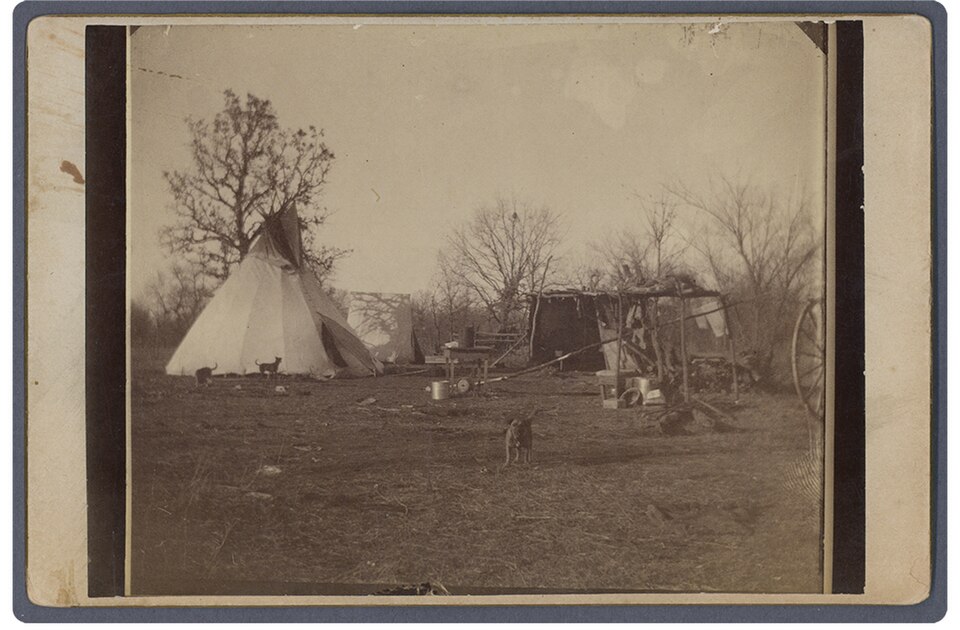

The Comanche people, now recognized as a sovereign Native American nation based in Oklahoma, trace their origins to the Eastern Shoshone tribes of the Great Basin region, particularly near present-day Wyoming. Linguistic and cultural similarities link them directly to the Shoshone, from whom they separated in the late 1600s (Kavanagh, 1996; Foster, 1991). The migration that followed this split saw the Comanche moving southeastward across the Rocky Mountains and onto the southern Great Plains, a transition made possible by their early and enthusiastic adoption of the horse, acquired through trade and raids following Spanish contact (Hämäläinen, 2008; Newcomb, 1961).

This newfound mobility transformed the Comanche into one of the most formidable equestrian cultures in North America. They became known for their horsemanship, which enabled them to dominate trade, warfare, and hunting across a vast territory known as Comancheria. This area, at its height in the 18th and early 19th centuries, covered parts of present-day Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Colorado, and Kansas (Hämäläinen, 2008; Wallace & Hoebel, 1952). Their command over the horse was so significant that Spanish colonists referred to them as “Lords of the Plains,” and their mounted raids could cover hundreds of miles in a single campaign (Hämäläinen, 2008).

Comanche Society and Culture

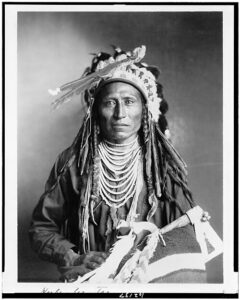

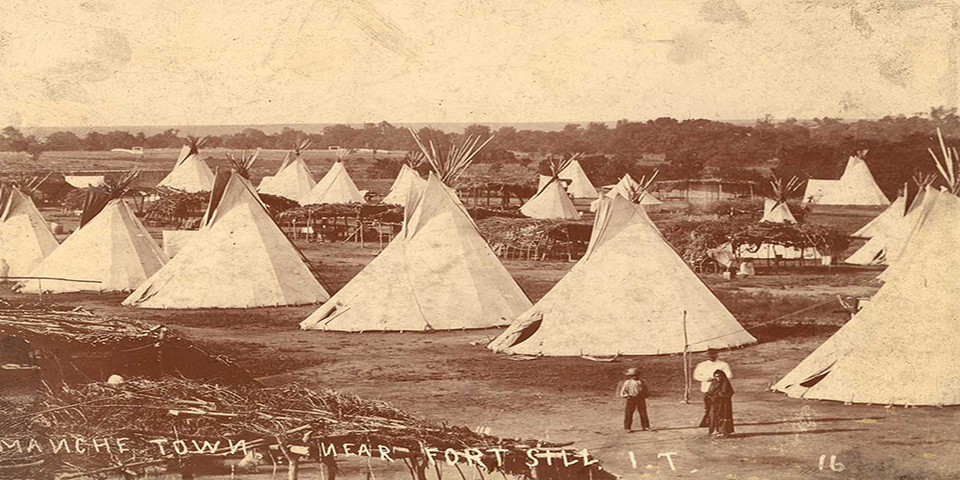

The Comanche society was organized into autonomous bands, including the Yamparika, Nokoni, Penateka, Kwahadi, and Kotsoteka. Each band operated semi-independently under a peace chief, while war chiefs gained influence during times of conflict. Leadership was based on personal achievement and consensus rather than heredity. Decision-making was communal, and leaders had to persuade rather than command (Kavanagh, 1996; Wallace & Hoebel, 1952). Social status was often tied to prowess in hunting and warfare, particularly in stealing horses and taking captives.

The Comanche’s religion was animistic, focusing on spiritual power residing in natural objects, animals, and celestial forces. Vision quests, sacred bundles, and dream interpretation were central to spiritual life. Medicine men acted as intermediaries between the spiritual and physical worlds, providing healing and guidance. By the late 19th century, the Peyote religion—later known as the Native American Church—had gained prominence and continues to be a key part of the spiritual identity for many Comanche (Fowler, 1982; Mooney, 1891; Stewart, 1987).

The Comanche were both feared and respected for their military prowess. Their economy was based on hunting, raiding, and trade. They were particularly effective at capturing and domesticating horses, which they used to launch raids on Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo-American settlements. Captives were taken during these raids—some to be ransomed, some to serve as labor, and others to be adopted. Children were the most likely to be fully absorbed into Comanche culture, sometimes forgetting their previous lives entirely. This included both Native and White children (Fehrenbach, 1974; Wallace & Hoebel, 1952; Brooks, 2002).

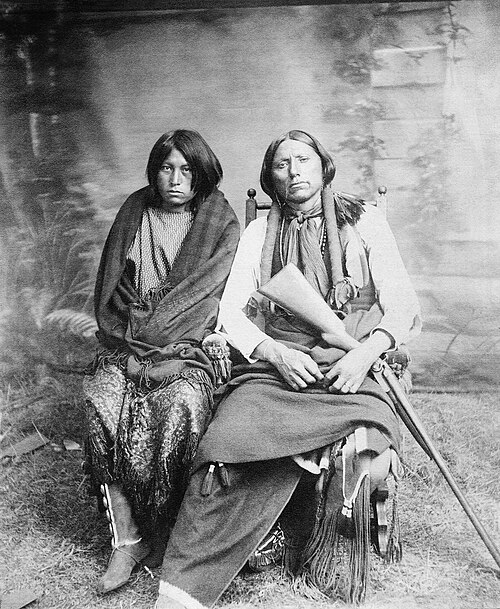

The Fort Parker Raid

One of the most emblematic stories of Comanche history is the abduction of Cynthia Ann Parker in 1836 during the Fort Parker raid. She became the wife of Peta Nocona, a prominent war chief, and gave birth to Quanah Parker. Quanah would become a bridge between the Comanche’s nomadic past and their life on the reservation. He led his people in the last significant resistance during the Red River War and, after defeat, became a statesman and advocate for Comanche interests. He adopted aspects of Euro-American culture, including ranching and formal dress, while maintaining his Comanche identity and helping to establish the Native American Church (Hagan, 1993; Neumann, 2001).

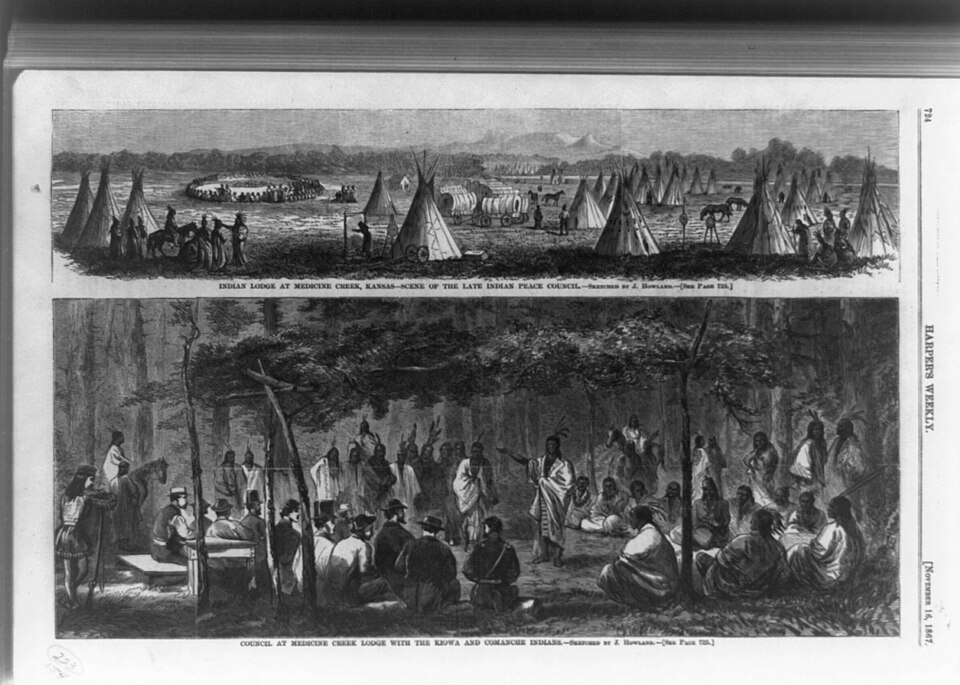

The Comanche formed strategic alliances with the Kiowa and occasionally with the Wichita to enhance their power in the region. Their dominance displaced the Apache and other tribes like the Tonkawa, who were often pushed further south or confined to smaller territories. Their rivalry with the Osage and Ute was especially fierce, with battles fought over hunting grounds and trade routes (Hämäläinen, 2008; Foster, 1991).

From War to Nationhood

In the 19th century, American expansionism intensified, and with it, the conflict between settlers and Plains tribes. The U.S. military adopted a strategy of total war, targeting not only warriors but also villages and food supplies. The 1874–75 Red River War marked a turning point. The destruction of the Comanche’s horses at Palo Duro Canyon and the mass slaughter of the buffalo, their primary food source, led to their surrender (Utley, 1984; Richardson, 1993).

Once confined to the reservation system in Indian Territory, the Comanche faced forced assimilation through the Dawes Act and boarding school policies that banned their language and culture. Despite these efforts, Comanche traditions persisted. In the 20th century, the tribe reconstituted a form of self-government under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. Today, the Comanche Nation operates a complex administrative structure with departments for housing, education, health, and cultural preservation (Comanche Nation, 2023; Deloria & Lytle, 1983).

As of the 2020 U.S. Census, there are approximately 17,000 enrolled members of the Comanche Nation. The tribe is headquartered in Lawton, Oklahoma, and hosts events such as the annual Comanche Nation Fair, which helps maintain cultural continuity. Language revitalization efforts have produced textbooks, online courses, and youth immersion programs. Comanche veterans have served in all major U.S. conflicts, and the nation remains a proud contributor to broader American society while preserving its unique heritage (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021; Comanche Nation, 2023).

Conclusion

Despite centuries of upheaval, the Comanche remain a resilient people, embodying a complex legacy of warfare, adaptation, diplomacy, and survival. Their story is not confined to the past—it rides onward, carried by descendants who still honor the strength, wisdom, and spirit of their ancestors. From their early days as a Shoshone offshoot to their rise as masters of the Southern Plains, the Comanche have demonstrated extraordinary adaptability, courage, and cultural depth. Though challenged by war, disease, displacement, and the relentless pressure of colonization, they never vanished. Instead, they transformed. Today, the Comanche Nation continues to preserve its language, traditions, and sovereignty, thriving as both a reminder of its history and a vibrant part of modern Native America. Their journey speaks to the broader human story: of survival, identity, and the power of a people to endure and shape their destiny across centuries. In remembering the Comanche, we do more than recount battles and treaties—we listen to the heartbeat of a nation that still echoes across the plains.

Sources:

- Hämäläinen, Pekka. The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press, 2008.

- Kavanagh, Thomas W. Comanche Ethnography. University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

- Fehrenbach, T.R. Comanches: The Destruction of a People. Knopf, 1974.

- Hagan, William T. Quanah Parker, Comanche Chief. University of Oklahoma Press, 1993.

- Fowler, Loretta. Shadows on the Plains: Native Traditions and the Cheyenne and Arapaho. University of Oklahoma Press, 1982.

- Richardson, Rupert N. The Comanche Barrier to South Plains Settlement: A Century and a Half of Savage Resistance to the Advancing White Frontier. Arthur H. Clark Company, 1933.

- Wallace, Ernest & Hoebel, E. Adamson. The Comanches: Lords of the South Plains. University of Oklahoma Press, 1952.

- Mooney, James. The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890. Bureau of American Ethnology, 1891.

- Foster, Morris W. Being Comanche: A Social History of an American Indian Community. University of Arizona Press, 1991.

- Neumann, Caryn. “Quanah Parker.” In American National Biography Online, Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Newcomb, W. W. The Indians of Texas: From Prehistoric to Modern Times. University of Texas Press, 1961.

- Utley, Robert M. Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866–1891. University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

- Stewart, Omer C. Peyote Religion: A History. University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

- Brooks, James F. Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands. University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

- Deloria, Vine Jr., & Lytle, Clifford M. The Nations Within: The Past and Future of American Indian Sovereignty. Pantheon Books, 1983.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2020 Census of Population and Housing. https://www.census.gov

- Comanche Nation Official Website. https://www.comanchenation.com/