Introduction

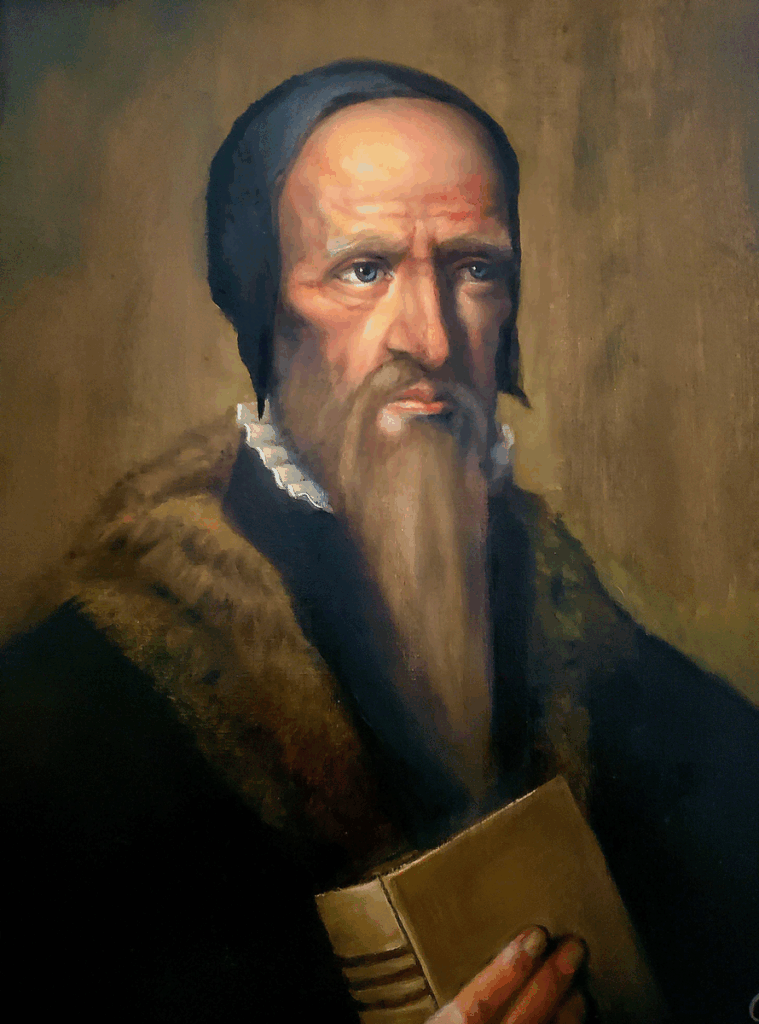

John Calvin was one of the most influential figures in the Protestant Reformation. His teachings not only shaped the direction of Reformed theology in the 16th century but continue to impact Christian beliefs and church practices today. Calvinism, the system of theology that grew from his work, has gone through many changes over the centuries, some staying true to Calvin’s original teachings and others branching into new forms. Who was John Calvin? What did he believe and teach? How did his background influence his ideas, and how has Calvinism changed after his passing? Lastly, what does modern Calvinism look like today? Hopefully, this blog will make it understandable for those who may not be familiar with theological terms or church history. This blog is for informational purposes only. The author is not a Calvinist and presents this content solely for educational value.

Who Was John Calvin?

John Calvin was a French theologian and reformer born on July 10, 1509, in Noyon, Picardy, in northern France. He died on May 27, 1564, in Geneva, Switzerland. Initially trained in law at the University of Orléans and later exposed to Renaissance humanist ideals, Calvin eventually broke with the Roman Catholic Church around 1530. His legal training gave him a structured and analytical mind, which influenced his theological writings. This background in law likely contributed to his emphasis on divine justice, covenant theology, and orderly church governance (McGrath, Reformation Thought, 2012).

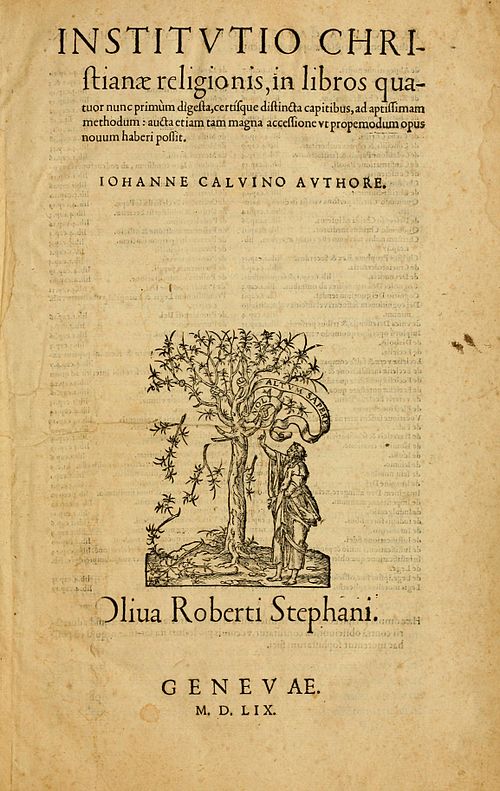

Calvin’s most influential work, Institutes of the Christian Religion, first published in 1536 and revised over his lifetime, systematically presented Protestant theology. Fleeing persecution in Catholic France, Calvin found refuge in Basel, then moved to Geneva, where he spent most of his adult life organizing church reforms. His teachings stressed God’s absolute sovereignty, human depravity, and predestination.

Calvin’s motivation stemmed from a deep conviction that the Church needed to return to the authority of Scripture and away from what he saw as human-centered traditions of the Roman Catholic Church. He believed in building a disciplined and holy community that mirrored biblical principles. His exile and suffering during periods of political and religious unrest influenced his emphasis on God’s providence—that God was actively and sovereignly involved in all human affairs, even in suffering (Gordon, Calvin, 2009).

The Theology of John Calvin

John Calvin’s theology can be summarized by the acronym TULIP, although this summary came later and was formalized by his followers. His major theological contributions include the sovereignty of God, the total depravity of humanity, the unconditional election of the saved, limited atonement (Christ died only for the elect), irresistible grace, and the perseverance of the saints. Calvin strongly emphasized that salvation was entirely a work of God, not based on any merit in humans (Calvin, Institutes, Book III).

Calvin also believed in what is called “double predestination”—that God not only predestines some individuals to salvation but also others to damnation (Institutes, III.23.5). This idea was not invented by Calvin but developed from Augustine’s teachings and refined in response to opponents like Pighius. For Calvin, this wasn’t merely a theoretical point but a reflection of God’s justice and glory.

His ecclesiology (doctrine of the church) also differed from both Roman Catholic and Lutheran models. Calvin believed in a well-ordered church governed by elders (presbyters) and pastors, with a strong emphasis on discipline and teaching. Worship was to be simple, Scripture-centered, and free from human inventions. Calvin’s Geneva became a model of Reformed Protestant community life.

Calvin’s personal background played a key role in shaping these doctrines. His legal training helped develop a systematic approach to theology. His humanist education gave him the tools to interpret Scripture in its original languages and contexts. His experience of exile and persecution strengthened his view of God’s providence and the importance of moral discipline within a Christian community (Gordon, Calvin, 2009).

The Development and Divergence of Calvinism

After Calvin’s death in 1564, his ideas were expanded and institutionalized by theologians such as Theodore Beza and adopted in various confessional documents like the Belgic Confession (1561), the Heidelberg Catechism (1563), and the Canons of Dort (1619). These writings helped establish “Reformed” churches in places like the Netherlands, Scotland, parts of Germany, and eventually North America.

Over time, Calvinism diversified. In the 17th century, Reformed orthodoxy focused heavily on scholastic definitions and systematic theology. In the 18th century, Calvinist thought influenced Puritanism in England and colonial America, contributing to what became American evangelicalism. During the 19th century, Calvinism played a significant role in shaping Presbyterian and Reformed denominations.

By the 20th and 21st centuries, Calvinism branched into multiple streams:

- Neo-Calvinism: Championed by Abraham Kuyper and Herman Bavinck, emphasizing God’s sovereignty over all of life, not just salvation. Kuyper famously said, “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ… does not cry, ‘Mine!’” (Kuyper, Lectures on Calvinism, 1898).

- New Calvinism: A recent revival, especially among younger evangelicals, characterized by figures like John Piper, Tim Keller, and Matt Chandler. This movement emphasizes Reformed soteriology (especially predestination), but often pairs it with modern worship styles and a missional focus.

- Liberal or Moderate Calvinism: Some modern theologians who value Calvin’s emphasis on God’s sovereignty and Scripture but reject strict doctrines like limited atonement or double predestination.

- Hyper-Calvinism: A fringe view that discourages evangelism and emphasizes God’s sovereignty to the exclusion of human responsibility.

- Five-Point Calvinists vs. Four-Point Calvinists: Some Christians embrace all five points of TULIP, while others reject limited atonement, affirming universal atonement but keeping the rest of the framework.

Modern Calvinism differs from Calvin in several key ways:

- Calvin did not separate the five points as a system—this was done posthumously in response to Arminianism at the Synod of Dort (1618–19).

- Calvin emphasized union with Christ and sanctification more than some modern Calvinists, who focus primarily on predestination.

- Calvin’s worship practices and church polity were more rigid and simpler than what is common in modern Calvinist churches.

Despite these differences, Calvin’s legacy continues in churches that affirm the Reformed confessions and uphold doctrines like God’s sovereignty, the authority of Scripture, and salvation by grace.

Calvin also placed a strong emphasis on the role of the Holy Spirit in the life of the believer and the church. He taught that the Holy Spirit is the one who makes the work of Christ real and effective in our lives. According to Calvin, the Spirit is the means by which believers are united with Christ, receive faith, are regenerated (or born again), and grow in holiness. The Holy Spirit opens the eyes of people to understand Scripture and enables them to respond to God’s call. Calvin believed that the Spirit does not speak apart from the Word of God, but always works in harmony with Scripture to convict, comfort, and guide the believer. This belief helped shape his emphasis on the authority of Scripture and the inner work of grace (Calvin, Institutes, Book III, chapters 1–2).

Today, mainstream Calvinism still holds firmly to the idea that God is in complete control of everything, including who will be saved. Most Calvinist churches teach that people cannot earn salvation or choose God on their own—rather, God chooses people to be saved, and His grace is what changes their hearts. These churches usually emphasize Biblical preaching, genuine worship, and a strong sense of God’s greatness. While they may differ in how they handle worship or church rules, they generally agree that salvation is entirely up to God, not something humans can cause or control. This view is still found in many Presbyterian, Reformed, and Baptist churches around the world.

Conclusion

From the streets of Geneva to pulpits around the world today, Calvin’s influence still echoes through Christian thought and church life. Though Calvinism has developed into many streams over the centuries, at its heart remains the same unshakable truth Calvin championed: God is sovereign, His Word is supreme, and salvation is entirely a gift of grace. Whether praised or debated, Calvin’s ideas continue to challenge people to think deeply about faith, grace, and the nature of God. For those exploring Christianity or church history, understanding Calvin and the development of Calvinism offers a powerful window into the ongoing story of the Church’s pursuit of truth.

Sources:

- Calvin, John. Institutes of the Christian Religion, trans. Ford Lewis Battles. Westminster Press, 1960.

- Gordon, Bruce. Calvin. Yale University Press, 2009.

- McGrath, Alister E. Reformation Thought: An Introduction, 4th ed., Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- Kuyper, Abraham. Lectures on Calvinism, Eerdmans, 1931 (orig. 1898).

- Beeke, Joel R., and Mark Jones. A Puritan Theology: Doctrine for Life. Reformation Heritage Books, 2012.

- Helm, Paul. Calvin: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2008.