Life is often described as a tapestry, woven from countless threads of experiences, choices, and unexpected turns. No two patterns are ever the same. Some lives are cut short in tragedy, while others stretch on toward success and endurance. Why one survives and another does not, or why one prospers while another falters, remains a mystery hidden within the wisdom of God alone. Only He sees the full design of the grand mosaic, with all its intricate details and meaning.

Ellis County, Texas

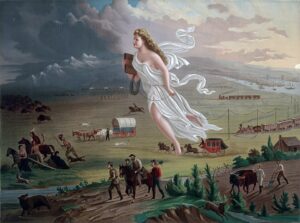

In the late 1850s, Ellis County, Texas, was still a wild and untamed land. Deer and antelope roamed freely, while wild turkeys and hogs foraged through the underbrush. Wolves, bears, and even panthers prowled the forests, sharing the streams with fish that glistened in the clear waters. These waterways wound their way through the countryside, framed by small hills and shaded by thick woodlands that occasionally opened into sunlit meadows. It was here that settlers hunted, not for sport, but to place food on the tables of their families.

The men and women who came to Ellis County carried with them stories from distant places. William Rowen, originally from New York, had first made his way to Ohio before finally settling just north of Ellis County by 1860, where he lived with his wife, Mary. Among his neighbors was Otwa Bird Nance, who had journeyed from Illinois. His brother, Quill Nance, also came from Illinois, and together the Nance brothers built farms that would anchor their families in Ellis County for generations. Not far away, Joshua G. Phillips, a Kentucky native born around 1819, brought with him valuable experience in making gunpowder when he moved to Ellis County about 1861. Another newcomer, Tillman Patterson, was born in Arkansas around 1830 and made the trek to Texas between 1855 and 1857, adding his story to the growing patchwork of pioneers.

During the turbulent opening of the Civil War, Texas found itself deeply divided. Governor Sam Houston, the legendary hero of San Jacinto and a former president of the Republic of Texas, refused to take the oath of allegiance to the Confederate States of America. Houston’s ultimate loyalty lay with the Constitution of the United States. For that reason, he would not abandon the Union. His refusal came at a price: the Texas legislature declared his office vacant and installed Lt. Governor Edward Clark as the state’s new chief executive.

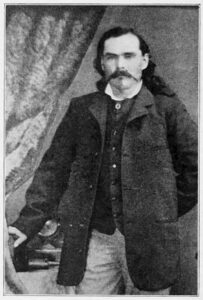

Under Clark’s watch, Texas began mobilizing for war. One of the most energetic figures to rise to prominence was William Henry Parsons, a 35-year-old newspaperman originally from New Jersey. Parsons carried himself with a restless energy and magnetic charm that seemed to inspire those around him. He was no stranger to combat, having already earned experience in the Mexican-American War, and the Confederacy quickly saw his value. Parsons was commissioned as a colonel and ordered to raise a mounted regiment for Texas.

By the summer of 1861, Parsons was on the move. Traveling through Ellis County, he appealed to the patriotic fervor of its citizens, calling for young men to defend their state. His efforts culminated in August at Rockett Springs, a small community about five miles north of Waxahachie. There, more than 1,000 eager recruits assembled, ready to trade farm tools for sabers and saddles. The unit they formed was first known as the Fourth Texas Mounted Dragoons. Once mustered into Confederate service, they were redesignated the Twelfth Texas Cavalry—but to history, they would be remembered simply as Parsons’ Brigade.

On the morning of September 11, 1861, the quiet community of Rockett Springs—today known simply as Rockett, Texas—was alive with anticipation. Crowds once more gathered to witness the ceremonies surrounding the newly formed regiment. Among them stood 18-year-old David Nance, the same young man mentioned earlier. Tall and lanky at six feet, with a thin, angular frame, he blended in with the throng of spectators who had come by wagon, horseback, or on foot to see the momentous occasion.

The dusty country roads around Rockett Springs overflowed with people. Families craned their necks, children clutched their parents’ hands, and neighbors leaned from their wagons to catch a glimpse. Men stood on tiptoe in the crowd, eager not to miss a single detail. The atmosphere pulsed with excitement: the roll of drums thundered across the gathering, banners snapped and rippled in the breeze, and martial music lifted the spirits of all present.

Later recollections give us a vivid window into the scene—capturing the sights, sounds, and emotions of Rockett Springs as it was on that September morning, 155 years ago.:

“At the hour of ten a.m., the bugle sounded and ten companies, comprising about twelve hundred men, formed a ‘hollow square’ in order to better perform the work at hand; this done, the marshal of the day (whose name is forgotten) demanded to know the nominations – First, for Colonel….[when] the name of Parsons was called by many voices…a proud form on as proud an animal glided into the open space and made a brief address to the volunteers around him, after which the marshal called for a vote and W.H. Parsons was unanimously elected. John W Mullins was elected Lieutenant colonel; E.W. Rogers Major;.”

The Powder Mill

As the Civil War deepened, the Confederacy’s most pressing need quickly became clear: weapons and gunpowder. Southern soldiers could not be sent into battle without arms, and local communities scrambled to find ways to supply them. In Waxahachie, part of that solution came in the form of William Rowen, a 50-year-old New York native who had made Ellis County his home.

Rowen was, unfortunately, an ardent secessionist, yet his personality revealed a gentler side. Known for his kind disposition and tireless work ethic, he was both respected and well-liked in the community. Though born in the North, his speech carried a softened Southern accent, and his bearing suggested a trace of noble lineage. Inside his home, shelves lined with books and journals testified to his intellect and wide-ranging interests. Rowen read deeply in philosophy, history, and religion, but he also studied the precise science and craft of gunpowder production—the very knowledge that would make his mill vital to the Confederate cause.

William Rowen’s wife, Mary, carried constant worry for her husband’s health. His work was grueling, and the dangers of gunpowder production weighed heavily on her mind. Rowen, ever quick with humor, would often lighten her fears with a jest, promising that he would “never allow a heart attack to deprive her of a good husband.”

Rowen was not alone in his venture. He partnered with Tillman Patterson, a younger man married to Ravia Mulkey. Ravia’s brother, Stephen Mulkey, played a critical role at the mill as its chemist. Rounding out the team was Joshua Phillips, a seasoned powder maker who had only recently settled in Ellis County but brought invaluable experience to the enterprise. Together, these men formed the backbone of Waxahachie’s gunpowder works.

To ensure their efforts had both structure and support, Rowen secured a contract with the state of Texas. Under the agreement, the state supplied the raw materials, and Rowen kept half the finished product as payment. This arrangement provided not only financial stability for the mill but also a reliable supply of desperately needed gunpowder for the Confederacy.

The mill itself was an ingenious, if makeshift, construction. Much of it was built from repurposed materials—an old horse mill, a blacksmith shop, and whatever timber could be spared. While the walls provided only minimal shelter from the elements, the foundation was sturdy enough for the dangerous work at hand. Ten small mules turned a treadmill that crushed and ground saltpeter and sulfur into powdery cakes, the essential base for gunpowder.

The compound sprawled across the site in what witnesses later described as “three clusters of dirty, barnlike structures interlaced with loading platforms, wooden tramways, service shelters, and storage sheds.” The principal buildings included the furnace shed, the roller mill, and the powder house, each containing crude and sometimes improvised machinery. The furnace shed, where intense heat and flying embers posed a constant danger, had to be set apart from the other buildings. It was here that chemist Stephen Mulkey spent most of his time. He was often heard grumbling about the suffocating heat inside, yet his skill in managing the volatile process was vital to the mill’s survival.

David Nance

Through negotiations with the Texas government, William Rowen secured an unusual but practical agreement: men serving in the military could be assigned to work in the powder-making industry. The need for skilled and dependable labor was great, and this arrangement provided both manpower for the mills and gunpowder for the state.

Among those who seized the opportunity was Quill Nance, a former neighbor of Rowen. He arranged for his son, David, to take part in the enterprise. Rowen himself had requested that the young man come under his supervision, recognizing both his potential and the urgent demand for trustworthy workers. Thus, David Nance—just eighteen years old, tall and wiry with the energy of youth—entered the dangerous world of the Powder Works in Waxahachie, Texas.

Despite his initial lack of knowledge in gunpowder production, young Nance quickly adapted and found satisfaction in his work in Waxahachie. His first day at the mill was on December 27th, 1862. Nance arranged to reside with William and Mary Rowen on Red Oak Road. This living arrangement granted him access to Rowen’s library, where he spent countless hours immersed in reading. Nance also enjoyed socializing within the local community.

Given the understaffed conditions, Nance’s presence brought relief to the other four men at the mill. Joshua Phillips and Tillman Patterson forged a strong friendship, and despite the laborious and repetitive nature of their work, the group managed to produce substantial quantities of gunpowder, amounting to thousands of pounds. Their collective efforts contributed to meeting the pressing demand for ammunition.

An Unforgettable Day

The laborious work at the mill left these men very dirty. A bathhouse was available for them to clean up and change clothes before leaving at the end of the day, as their work attire became saturated with gunpowder residue.

On April 29th, 1863, at around 4:00 pm, Stephen Mulkey made the decision to leave for the day. He headed towards the bathhouse to freshen up and encountered his brother-in-law and fellow employee, Tillman Patterson, who had also decided to leave early. Mulkey and Patterson left together, intending to spend the remainder of the day working in their garden.

David Nance was working in the mill grinding cake when Rowen came in, and together they and Phillips decided that they should also stop work for the day.

At just that moment, about 4:15 pm, a bright flash illuminated the mill, followed by a deafening explosion in one of the mortars. The mill suddenly filled with a bitter, pungent smoke. Subsequent explosions reverberated through the building, one of which tore the rear of the building away. These secondary explosions shook the very foundations of the building and inhibited the men from fleeing.

In the midst of the chaos, Nance attempted to flee through the front door. However, the force of the explosions knocked him to the ground, and his powder-saturated clothing ignited, engulfing his entire body in flames. His entire body began to be scorched by the fire as his clothes were literally being “burned off.” In a desperate struggle, he managed to regain his footing, rushing through the doorway while frantically clawing at his burning clothes.

Thrown backward from the entrance into the wreckage of a burning wall, Rowen and Phillips desperately attempted to make it to the exit, their clothes not yet ignited. At least 20 seconds or so after Nance exited the building, Rowen and Phillips made their way out of the mill. About “ten steps from the door,” Phillips tripped over an open barrel full of powder. The spilling powder ignited and then, catching their clothes on fire, turned both men into human torches. Both men ran through the front door and flung themselves into an open well.

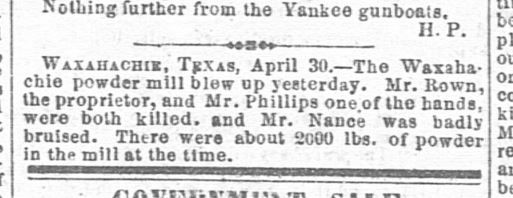

Seconds later, the fire ignited approximately 800 lbs of gunpowder which was in process. This last and largest explosion shook the entire town “like an earthquake.” Embers pelted the area out of an enormous billowing pillar of smoke. Burning embers caused small fires on the top of the powder house containing 9000 pounds of finished powder. Volunteer firefighters quickly arrived and rushed to the powder house, putting out the flames before a greater catastrophe could occur. All that remained of this powder mill was the warehouse that held the finished powder. The explosions killed most of the mules, and smoke rose from pieces of rubble lying in the street as far as two blocks away. The buildings around the powder plant had visible scars from the fire.

The explosion left Joshua Phillips unrecognizable due to severe burns. Despite enduring unimaginable agony, he lived for only five hours. Phillips identified William Rowen before passing away, confirming that Patterson and Mulkey were not inside the building. Rowen, also severely burned, fought for survival but succumbed to his injuries approximately 12 hours later.

In the climate of paranoia and fear indicative of the time, immediate rumors told of a man seen at the plant just before the explosion. The man and his wife were staying at the Rogers Hotel. This man was said to have disappeared just after the explosion. In such a dangerous, volatile job, one needs to look no further than the occupation itself for the cause of the explosion. B.P. Galloway postulates that the explosion may have started directly in the mortars where Nance was working. Nance’s own account of the bright flash there lends to this theory. The initial flash, the secondary explosions, and the 800 pounds of mill cake exploding would account for the remaining and increasing blasts.

The aftermath of the Blast

After the terrible explosion, David Nance was carried to the Rowen home, where a local physician tended to his burns. The next day, his parents arrived and brought their son back home. His recovery was long and painful. For two full months, he lay bedridden, dependent on others for even the simplest tasks. His mother patiently fed him by spoon, nursing him through the worst of his injuries. It was not until July of 1863 that Nance regained enough strength to stand and eventually return to work.

When he did, he found employment with his uncle, Otwa Nance, at a wool-processing plant. The work was steady, and David later remarked that handling the oily wool toughened his hands, giving him back some of the strength he had lost. By the autumn of that year, his resilience drove him to rejoin his Confederate company, eager to be back among his fellow soldiers despite all he had endured.

Others connected to the powder works met different fates. Joshua Phillips, mortally burned in the explosion, died without leaving a will. His grave lies in Waxahachie Cemetery, and his probate, dated May 18, 1863, was handled by his widow, Lucy. Joshua’s friend and co-worker, Tillman Patterson, signed the inventory of Phillips’s belongings. Lucy Phillips never remarried and lived more than half a century longer, passing away on August 8, 1919.

Mary L. Rowen, left a widow by the tragedy, remained in Waxahachie until her own death in 1894. She, too, rests in Waxahachie Cemetery. Stephen Mulkey moved west to Fort Worth, where he lived out the remainder of his life. Tillman Patterson stayed in Ellis County, where he continued farming until his death on May 25, 1893. Like Phillips and the Rowens, he was laid to rest in Waxahachie Cemetery.

David Nance’s Later Years

David Nance survived the war and eventually made his way to Fannin County, where he found work as a bookkeeper. There he married Miss Sallie M. Hackley and purchased a farm, beginning a new chapter of his life. In time, he returned to his family’s old home place in Dallas County, where he spent the remainder of his years.

As he grew older, Nance often reflected on the tragedy in Waxahachie. Of the three men trapped inside the powder mill, he alone had lived to tell the story. He also recalled other moments throughout his life when he narrowly escaped death or serious injury. With humility, he remained convinced that the hand of God had been upon him. His family carried on that legacy of faith—his grandson, Don Heath Morris, became a respected Bible scholar and later served as President and Chancellor of Abilene Christian University.

For others, the story ended far sooner. William Rowen, Joshua Phillips, and many more never saw the war’s conclusion. Yet Ellis County endured the upheaval, its landscapes and people forever changed. The valleys and rolling hills still cradled streams, but the rich abundance of fish and game that once sustained settlers had largely faded. The Ellis County of the 1860s survives now only in memory—woven into family histories, preserved in a scattering of records, and faintly echoed in the few memorials that mark the past. Of the powder mill and of Parsons’ Brigade, little remains but stories passed down, fragile reminders of a turbulent, vanished era.

Conclusion

In the end, perhaps the clearest perspective on the turbulent years of the 1860s in Ellis County comes from the words of one who lived through them. David Nance’s reflections offer both a window into the Civil War era and the lessons drawn from the choices he made along life’s uncertain roads.

In 1860, Nance witnessed enslaved men and women beaten nearly to death. Though horrified by the brutality and personally opposed to slavery, he nevertheless fought for the South, believing at the time that Southerners should decide for themselves whether to preserve the institution. Decades later, with the distance of age and experience, he looked back with deep regret. In 1908, a record noted his words: “…if there is any one act of his whole life which he regrets more than another, it is his entering the army. He regrets, first, because he wishes he had never assisted in protecting an institution so fraught with evil as human slavery; second, because war is murder, and murder has no mercy in it. Then, he entered the army against his father’s will, and he regrets it for that too.”

The legacy of the powder mill itself lingered long after the smoke cleared. In the 20th century, the First Baptist Church stood on or near the site of the old mill. During construction on an addition, workers reported finding scorched soil and charred layers beneath the ground—silent evidence of the fiery disaster that had shaken Waxahachie more than half a century earlier.

Bibliography

A Memorial and Biographical History of Ellis County. Chicago, Illinois: Lewis Publishing

Company, 1892

Ancestry.com. 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA:

Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch. Original

data: 1860 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653,

1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.

(accessed March31,2017) www.ancestry.com

Galloway, B.P., The Ragged Rebel; A Common Soldier in W. H. Parsons’ Texas Cavalry, 1861-

1865. Abilene, Texas: Abilene Christian University Press , 2010

Champion, Louella and Murray, Jonnie Lee. “African Methodism in Ellis County”.Sims

Library, Waxahachie Texas.

Dictionary.com. (accessed 3/29/3017) www.dictionary.com.

Findagrave. (accessed 3/29/2017) www.findagrave.com

Esberger, Karen Kay. Images of America; Midlothian. Texas,Arcadia Publishing. 2008

Hancock, Billy R. 1976. “An Amiercan Heritage Lecture series; Pre Civil war days in Ellis

County”. Notbook of photocopied lectures. Sims Library, Waxahachie Texas,

Richardson, John I. Civil War Letters and Military Records, Members of Company F, 12th Cavalry , Ellis Rangers, Parsons’ Brigade Reg’t Texas Volunteers. 1860-1862

This unpublished material can be located at Sims Library in Waxahachie, Texas.

Richardson, Rubpert N.; Anderson, Adrian; Wintz, Cary D.; Wallace, Earnest. Texas;

The Lone Star State. Prentice Hall. Boston. 2010.

Stott, Kelly McMichael. Waxahachie; Where Cotton Reigned as King. Texas: Arcadia

Publishing. 2002.

Handbook of Texas Online; Published by the Texas State Historical Association, Austin, Texas.

2017 www.tshaonline.org/handbook/search

“County Established by Legislature in 1849.” Newspaper Clipping, Vertical File, Sims

Library, Waxahachie Texas.

Hawkins, Edna Davis; Stone, Ruth; Brookshire, Ida M.; Tolleson, Lillie; The Ellis County

History Workshop. History of Ellis County, Texas. Waco, Texas; Library Binding

Company, 1972

Interview with Mollie Phillips; 1936. Transcribed from Newspaper Clipping, Waxahachie Daily

Light. Vertical File. Sims Library. Waxahachie Texas.