Introduction

The American Civil War (1861–1865) was the deadliest conflict in United States history, claiming more lives than all previous American wars combined. More than a struggle of armies, it was a battle over the meaning of the Union and the future of human freedom. Families were torn apart, entire regions scarred, and the country tested to its very core. By tracing the causes, campaigns, battles, leadership, and consequences in order, we can see how the United States endured its greatest crisis and emerged transformed.

Causes and Secession

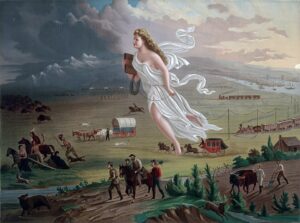

The roots of the Civil War lay in decades of sectional conflict between the North and South. These conflicts were political, economic, social, and cultural. The term ‘sectional’ refers to the deep divisions between regions, with the North and the South functioning almost like separate societies that held conflicting priorities. The Northern states developed more rapidly into an industrial and urban economy, while the Southern states remained largely agricultural, dependent on plantation systems and enslaved labor. Political disputes arose over tariffs, states’ rights, and most significantly the expansion of slavery into western territories. Each new territory threatened to upset the balance of power between free and slave states, intensifying distrust and hostility between the regions (McPherson, 1988; Foner, 2010). The expansion of slavery into new territories repeatedly inflamed national debate.

The Missouri Compromise (1820), Compromise of 1850, and Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854) each attempted to ease tensions, but none resolved the central issue. Violence in Kansas and the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) decision, which denied Congress’s power to restrict slavery, convinced many Northerners that the “Slave Power” endangered democracy. Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 on a platform opposing the spread of slavery triggered the secession of eleven Southern states, beginning with South Carolina in December 1860. These states formed the Confederate States of America under President Jefferson Davis, with Richmond, Virginia, as their capital (McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 1988).

1861: The War Begins

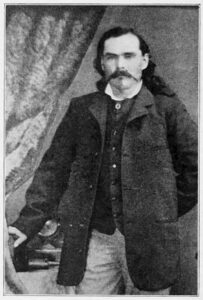

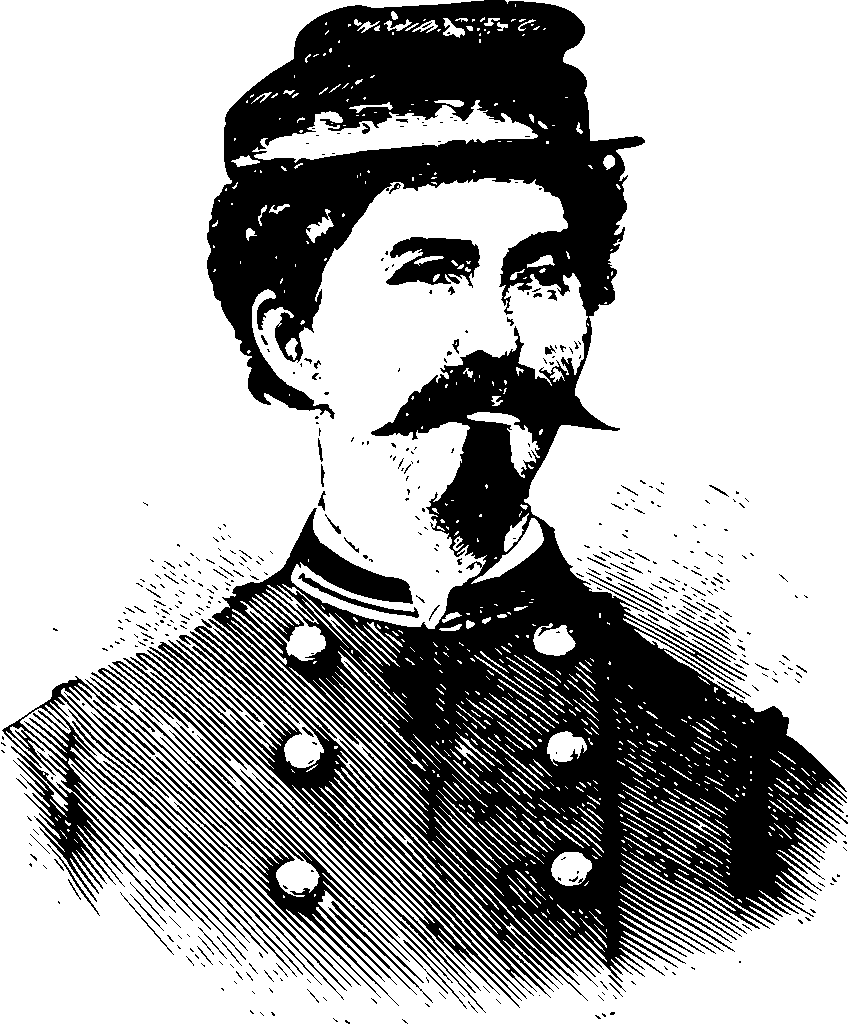

The war began in April 1861 when Confederate forces under General P. G. T. Beauregard fired on Union troops at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers, prompting four additional states, including Virginia, to secede. Before Bull Run, there were smaller skirmishes such as the clash at Big Bethel in Virginia (June 10, 1861) and fighting along the border states, but these were limited in scope. The first large battle, First Bull Run/Manassas (July 21, 1861), was intended by Union leaders to be a swift strike toward Richmond that might bring an early end to the rebellion. The Union Army under General Irvin McDowell marched south from Washington aiming to disperse Confederate forces and open the road to the Confederate capital. Instead, the battle ended in a Confederate victory under Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston. The Confederate strategy had been largely defensive, aiming to block the Union advance toward Richmond, but timely reinforcements allowed them to launch a counterattack that routed Union forces. The outcome demonstrated the war would be longer and bloodier than expected (McPherson, 1988; Eicher, 2001). Fighting also erupted in Missouri at Wilson’s Creek (August 1861), securing much of the state for the Union (Eicher, The Longest Night, 2001). At the close of 1861, both sides had mobilized their armies, the Confederacy had demonstrated it could win on the battlefield, and the Union realized the struggle would be far longer and costlier than initially imagined—setting the stage for the campaigns of 1862.

1862: Expansion of the War

In the West, Union generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman captured Forts Henry and Donelson (February 1862), forcing Confederate withdrawal from Kentucky and much of Tennessee. The Battle of Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862) was among the war’s bloodiest, revealing the new scale of combat (Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative, 1958). That same spring, Union Admiral David Farragut seized New Orleans (April 1862), giving the Union control of a vital port.

In the East, Union General George B. McClellan advanced on Richmond during the Peninsula Campaign (spring 1862). Confederate General Robert E. Lee, newly in command, forced McClellan to retreat in the Seven Days Battles (June–July 1862). Lee’s victories at Second Bull Run (August 1862) gave the Confederacy momentum. In September, Lee invaded Maryland but was checked at the Battle of Antietam (September 17, 1862). Though tactically inconclusive, it was the bloodiest single day in U.S. history and gave Lincoln the opportunity to issue a preliminary proclamation of emancipation, warning that enslaved people in Confederate-held territory would be declared free if rebellion continued into the new year (Foner, The Fiery Trial, 2010; McPherson, 1988).

In the Trans-Mississippi, Union victory at Pea Ridge (March 1862) secured Missouri for the Union, while the Battle of Glorieta Pass (March 1862) stopped Confederate attempts to seize New Mexico and the Southwest (Shea & Hess, Pea Ridge, 1992). By the end of 1862, the Union had secured major victories in the West and along the Mississippi, but Confederate resistance in the East remained strong. Both sides recognized that the conflict had escalated into a protracted, nationwide war that would demand far greater sacrifice.

1863: The War Turns

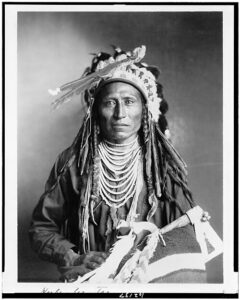

On January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation took effect, formally declaring enslaved people in Confederate-held territory free. This measure reframed the war as a struggle to preserve the Union and end slavery. Nearly 200,000 African Americans would serve in Union forces, bolstering manpower and undermining the Confederacy (Berlin, Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1982). The Emancipation Proclamation was received in different ways: many enslaved people treated it as an immediate call to claim their freedom, fleeing to Union lines whenever possible (Berlin, 1982). African American communities in the North celebrated it as a long-awaited step toward liberty. In contrast, Confederates dismissed or ignored it, since it applied only to areas outside Union control. Some Northern Democrats, known as ‘Copperheads,’ criticized the move, arguing it would prolong the war, while abolitionists praised it as a turning point (McPherson, 1988; Foner, 2010).

In the East, Lee’s victory at Chancellorsville (May 1863) was costly, as he lost Stonewall Jackson. Lee invaded Pennsylvania but was defeated at Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863) by Union forces under George Meade. Gettysburg, the war’s largest battle, marked a decisive turning point. The battle was also one of the most destructive of the entire war, producing more than 50,000 casualties in just three days and leaving a landscape filled with death and suffering (McPherson, 1988; Faust, 2008). Later that year, President Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address (November 19, 1863) at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. In just a few minutes, he redefined the Union’s cause as one of national unity and equality, framing the war as a test of whether a nation “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” could endure (McPherson, 1988).

In the West, Grant besieged Vicksburg (May–July 1863), which surrendered on July 4, giving the Union full control of the Mississippi River. At nearly the same time, Union forces also captured Port Hudson, Louisiana (May–July 1863), which surrendered on July 9 after a long siege, further ensuring complete Union dominance of the Mississippi (Eicher, 2001). The twin Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg shifted momentum. Later in the year, the Union secured Tennessee after victory at Chattanooga (November 1863), opening the Deep South to invasion (McPherson, 1988). That summer also saw unrest in the North during the New York City Draft Riots (July 13–16, 1863), violent protests against conscription that revealed divisions over emancipation and the war effort, leaving more than 100 people dead (McPherson, 1988; Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots, 1990). In addition, 1863 marked the official formation of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) following the Emancipation Proclamation, leading to large-scale enlistment of African American soldiers who played a vital role in later campaigns (Berlin, 1982). By the end of 1863, the Union controlled the Mississippi, had halted Lee’s northern invasions, and opened the way into the Deep South, while the Confederacy faced mounting losses and dwindling resources, yet continued to resist.

1864: Union Advance and Total War

Lincoln appointed Grant as general-in-chief in 1864. In Virginia, Grant launched the Overland Campaign (May–June 1864), fighting bloody battles at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor, before settling into the Siege of Petersburg (June 1864–April 1865).

In the West, Sherman advanced through Georgia in the Atlanta Campaign (May–September 1864), winning battles at Resaca, Kennesaw Mountain, and Atlanta. The fall of Atlanta on September 2 boosted Northern morale and helped ensure Lincoln’s reelection. Sherman’s March to the Sea (November–December 1864) destroyed Southern infrastructure, weakening Confederate resources (Grimsley, The Hard Hand of War, 1995). Fighting in the South during this period was widespread and sporadic, stretching across Georgia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas. Campaigns like Sherman’s march, combined with earlier battles in northern Georgia and Tennessee, demonstrated how the war in the South had no single front but instead erupted in multiple locations, exhausting Confederate resources and spreading destruction throughout the region. For context, the Battle of Chickamauga (September 19–20, 1863)—the bloodiest battle of the Western Theater—had occurred the previous year in northern Georgia, showing how contested and violent this region had already become before Sherman’s 1864 offensives (McPherson, 1988; Eicher, 2001).

In the Shenandoah Valley, Union forces under Philip Sheridan defeated Confederates at Third Winchester (September 1864) and Cedar Creek (October 1864). In Tennessee, Confederate General John Bell Hood suffered devastating defeats at Franklin (November 30, 1864) and Nashville (December 15–16, 1864), crippling the Confederate Army of Tennessee (Eicher, 2001). By the close of 1864, Union victories in Georgia, Tennessee, and the Shenandoah Valley signaled the collapse of Confederate military power, even as the Confederacy fought desperately to prolong the struggle.

1865: Confederate Defeat

In early 1865, Sherman marched north through the Carolinas, fighting at Bentonville (March 19–21, 1865). Grant pressed Lee at Petersburg, and after the Union victory at Five Forks (April 1, 1865), Richmond fell (April 2–3). In the days before the surrender, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, worn down by months of siege at Petersburg, attempted to retreat westward in hopes of linking up with other Confederate forces or finding supplies. Union armies under Grant, Sheridan, and Meade pursued relentlessly, cutting off escape routes and seizing vital supply trains at battles such as Sailor’s Creek (April 6, 1865).

Surrounded and outnumbered, Lee realized further resistance would only bring needless loss of life. He surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House (April 9, 1865). The site was chosen largely because the village of Appomattox Court House lay directly along Lee’s line of retreat and was where Union forces finally encircled his army. The McLean House, owned by Wilmer McLean, was selected simply because it provided a suitable and convenient space for the generals to meet (Eicher, 2001; McPherson, 1988). Other Confederate armies soon surrendered: Johnston to Sherman at Bennett Place (April 26) and Kirby Smith in the Trans-Mississippi (May 1865). The final clash at Palmito Ranch, Texas (May 12–13, 1865) occurred even after Appomattox (McPherson, 1988). By spring 1865, Confederate armies surrendered across the South, Richmond and other strongholds had fallen, and Union victory was assured, marking the effective end of the Civil War.

Consequences

The Civil War caused approximately 750,000 deaths, more than any other American conflict (Hacker, “A Census-Based Count of the Civil War Dead,” 2011). It preserved the Union and abolished slavery with the Thirteenth Amendment (1865). Reconstruction brought fierce struggles over rights, citizenship, and the reintegration of the South. The war resolved the greatest moral and political crisis in American history, but it also left deep challenges that shaped the nation’s future (Faust, This Republic of Suffering, 2008). In the end, the Civil War preserved the United States and destroyed slavery, but at the cost of unimaginable suffering. Its legacy reminds us that the freedoms and unity Americans often take for granted were forged in blood and sacrifice, and that the nation’s work of living up to its ideals continued long after the guns fell silent.

Bibliography

- Berlin, Ira, et al., eds. Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861–1867. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Faust, Drew Gilpin. This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. New York: Vintage Books, 2008.

- Foner, Eric. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York: W. W. Norton, 2010.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. 3 vols. New York: Random House, 1958–1974.

- Grimsley, Mark. The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy Toward Southern Civilians, 1861–1865. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Hacker, J. David. “A Census-Based Count of the Civil War Dead.” Civil War History 57, no. 4 (2011): 307–348.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Shea, William L., and Earl J. Hess. Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.