A Storm Behind the Headlines

In 1975, the heart of Washington, D.C., trembled—not from bombs or marches, but from whispered truths that finally found voice. A Senate investigation, officially called the Church Committee, peeled back the polished surface of American democracy and revealed what many feared: the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had infiltrated American media. The hearings uncovered not only foreign propaganda efforts but also a domestic web of influence—a revelation later known as “Operation Mockingbird.”

Though the term “Project Mockingbird” does not appear in any official CIA document, the name—popularized by journalist Deborah Davis in her 1979 book Katharine the Great—came to symbolize the covert influence of the CIA over American and international journalism during the Cold War. According to declassified documents and congressional testimony, the CIA collaborated with editors, journalists, and media executives to plant stories, suppress certain narratives, and sway public opinion both at home and abroad.

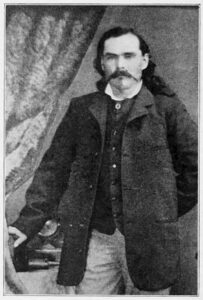

Carl Bernstein and the 400

The lid was blown wide open in 1977 when Carl Bernstein, half of the legendary team that exposed Watergate, published an article in Rolling Stone titled “The CIA and the Media.” Bernstein claimed the CIA maintained ties with more than 400 American journalists, including prominent voices at The New York Times, CBS, Time Magazine, and others. These individuals were said to engage in intelligence gathering, dissemination of pro-American narratives, and even undercover operations — with the full knowledge and approval of their employers. Bernstein’s investigation suggested this was not rogue behavior but an organized campaign of influence from within the highest offices of American media.

“Journalists were engaged to perform tasks for the CIA with the consent of their news organizations.” —Carl Bernstein

The Mighty Wurlitzer: Frank Wisner’s Orchestra

This covert influence operation was overseen in its early days by Frank Wisner, a high-ranking CIA officer and head of the Office of Policy Coordination. Wisner believed that controlling information was a strategic necessity in the Cold War, and he orchestrated a media network he likened to a “Mighty Wurlitzer.” Like a great organ playing many tunes at once, this system could push CIA-approved messaging through multiple news outlets across the globe—without the audience ever realizing they were hearing a carefully coordinated script.

Wisner and his team recruited journalists to act as willing or unwitting agents of influence. Some knowingly cooperated, while others were unaware they were contributing to intelligence goals. Regardless, the outcome was a media landscape subtly shaped by intelligence priorities rather than journalistic independence.

What the Church Committee Found

The Church Committee’s final report in 1976 The U.S. Senate’s Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities—known colloquially as the Church Committee—released its final report in 1976. It confirmed that the CIA had established relationships with journalists but refrained from naming names or detailing the full scope. The report stated:

“Approximately 50 of the CIA relationships involved individuals who were consciously providing the CIA with information… The remaining individuals were unaware that they were dealing with the CIA.” —U.S. Senate Report, 1976

In response to the public outcry, the CIA pledged to discontinue paid relationships with full-time American journalists. However, this policy contained significant loopholes: the agency could still use freelancers, foreign correspondents, and others not classified as full-time employees. Critics argued this was a semantic end-run around accountability.

Domestic vs. Foreign Propaganda

The U.S. government is legally restricted from engaging in propaganda operations against American citizens. However, information originally crafted for foreign audiences often found its way back to domestic media through a process known as “blowback.” Stories planted overseas were picked up by American wire services and newspapers, indirectly influencing public discourse at home. This created a murky gray area where the distinction between foreign and domestic messaging became impossible to uphold.

Why This Still Matters

Though officially discontinued, the legacy of Operation Mockingbird continues to resonate. The episode planted seeds of mistrust that remain today, particularly in debates over media bias, government transparency, and the reliability of information.

In late July 2025, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard publicly asserted that Operation Mockingbird remains active, condemning what she described as continued CIA-style influence operations embedded in modern media. During a July 31 interview with conservative commentator Benny Johnson, Gabbard characterized covert media manipulation as an ongoing threat. She claimed that undisclosed intelligence officials within the “deep state” continue leveraging mainstream outlets to undermine political figures—specifically former President Trump’s agenda.

More than a historical curiosity, Operation Mockingbird raises essential questions about democracy, freedom of the press, and the role of intelligence in shaping public perception. If the media is the fourth estate, then the discovery that it could be quietly steered by unelected officials should alarm any citizen committed to democratic ideals.

Moreover, this history should be remembered in light of modern accusations—ranging from social media manipulation to partisan disinformation campaigns. While today’s tools may differ, the question remains the same: Who controls the narrative?

(updated August, 2025)

Bibliography

Bernstein, Carl. “The CIA and the Media.” Rolling Stone, 20 Oct. 1977, https://carlbernstein.com/the-cia-and-the-media-rolling-stone/.

Simpson, Christopher. Blowback: America’s Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988.

U.S. Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. Final Report – Book I: Foreign and Military Intelligence. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976. https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/94755_I.pdf

Davis, Deborah. Katharine the Great: Katharine Graham and the Washington Post. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979.