First, We Must Discuss War

War is a complex and profound phenomenon that holds immense stakes for nations and their way of life. As G.K. Chesterton aptly put it, soldiers often fight not out of hatred for the enemy but out of love for what they hold dear. Throughout history, humans have faced the dilemma of choosing to fight for the resources they possess or yield to aggressors.

The fundamental question arises: are the devastating consequences of war justified for the sake of land or money? Is the principle for which one stands worth the cost that others are forced to pay? Is it merely a matter of the present moment, pitting violence against non-violence, or does a greater and compelling idea demand immediate action to prevent or halt further unimaginable carnage?

These questions have been the subject of debates for centuries and are likely to persist for centuries. Reflecting on historical events like the dropping of the atomic bombs by the United States during World War II, one must grapple with moral and practical considerations. Was the loss of life justified to prevent further casualties over the course of several more years of war? Was the scale of devastation too immense? Could an alternative approach have been pursued, allowing for a prolonged conflict with the slow attrition deaths of thousands, possibly millions, as the war raged on?

The horrors of war force us to confront the value of human life, the pursuit of peaceful alternatives, and the imperative to prevent future conflicts. Through ongoing discussions, analysis of historical events, and contemplation of ethical principles, we strive to deepen our understanding of the complexities surrounding war and its consequences.

The debate surrounding the necessity and consequences of war is unlikely to cease as humanity grapples with the perennial challenge of resolving conflicts peacefully and preventing the immense suffering it engenders.

A fundamental understanding that we must acknowledge is the concept of “the real world.” Unrealistic arguments claiming that we should have found better alternatives or engaged in more dialogue with our enemies fail to recognize the reality of certain situations. In the real world, there are times when discussions, negotiations, and deliberations can lead to a common understanding. However, there are also times when our adversaries use negotiations as a strategy to gain an advantage, buying time to rearm themselves and secure better positions. Whether in the realm of personal conflicts or on the grand stage of international warfare, the decisions of others often compel individuals to take action in order to protect their families, livelihoods, or ways of life.

It is essential to clarify that this writing does not aim to glorify or applaud the concept of war. War is the most atrocious and abhorrent act that humans can inflict upon one another. Nonetheless, dictated by the reality of circumstances beyond the control of those who desire peace, it is sometimes deemed necessary.

The acknowledgment of the real world and the recognition that there are instances where war becomes an unfortunate requirement should not undermine the ongoing pursuit of peace and the exploration of peaceful alternatives. It is crucial to strive for understanding, diplomacy, and preventing conflicts whenever possible. However, it is also necessary to confront the reality that, in certain circumstances, the demands imposed by external forces may leave individuals with no choice but to take up arms in defense of what they hold dear.

By acknowledging the complexities of the real world, we can foster a more nuanced understanding of the difficult choices faced by individuals and nations and work towards a future where peaceful resolutions prevail over the horrors of war.

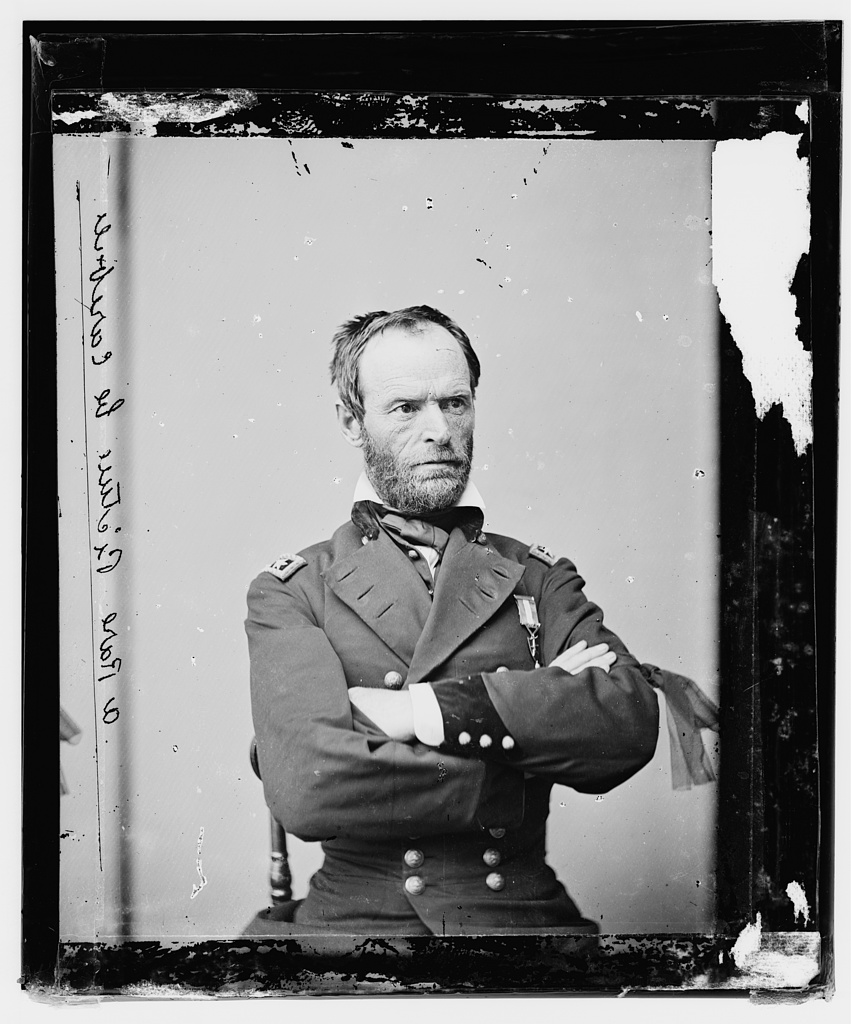

War’s depths and darkness can be incomprehensible to some, as its violence, pain, sorrow, death, and destruction defy easy understanding. However, there are those who, due to their life experiences, personal attributes, philosophies, or a combination thereof, possess the capacity to comprehend the realities of war and the actions required to achieve victory. General William Tecumseh Sherman exemplified such a figure.

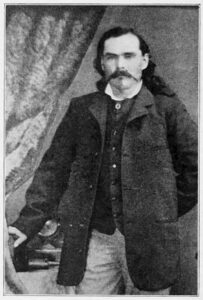

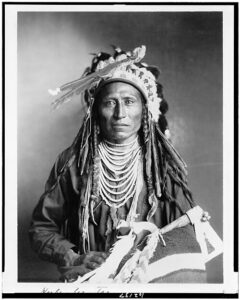

SHERMAN HAD A WARRIORS NAME FROM BIRTH

Before his birth on February 8, 1820, Tecumseh Sherman already carried the weight of a warrior’s title. His father, Charles Sherman, known for his diligent work ethic and unwavering principles, had already decided to name his son after the renowned Shawnee Chief, Tecumseh. Following Tecumseh Sherman’s birth, neighbors expressed skepticism about the decision to name a “white child” after an “Indian.” In response, Charles Sherman would assert that Tecumseh was a remarkable warrior, emphasizing the admiration he held for the legendary figure.

When Tecumseh Sherman was just 9 years old, his father passed away due to illness, leaving the family without adequate means of support. This sudden poverty compelled many of the children to leave home and seek shelter with extended family members or friends. In the case of Tecumseh, his neighbor and close friend of his father, Thomas Ewing, took him in and welcomed him into the Ewing household.

Under the care of the Ewing family, Tecumseh underwent a baptism into the Catholic Church, as urged by his foster mother. Since there was no “St. Tecumseh” to assign as his baptismal name, he was given the name “William.” Throughout his life, Sherman harbored concerns that he might pass away and leave his family without support, reliving the distressing circumstances he and his siblings had experienced. This fear reveals his apprehensions about providing for his loved ones and speaks to the lasting impact of the traumatic events on his mental and emotional well-being.

Sherman’s sentiments toward the Ewing family were always complex and contradictory. On the one hand, they had provided him with a home, treating him as their own son. His connection to the family became even stronger when he later married one of Thomas Ewing’s daughters, Ellen. However, alongside this deep gratitude, Sherman remained acutely aware that the Ewings were not his biological family. The impact of this situation on his life, military career, and leadership philosophy is not entirely clear, but it inevitably influenced his thought process to some degree.

While Sherman understood that his father’s death was not a deliberate act of abandonment, he still experienced a sense of being left behind and alone. In the arms of the United States Army, he sought solace and a newfound sense of belonging, viewing the military as his “family” in a profound way. The exact ways in which these conflicting emotions shaped his mindset and actions can only be speculated upon, but it is evident that they played a significant role in his personal journey.

SHERMAN HAD AN ERRATIC PERSONALITY

Sherman’s personality was characterized by its manic, mercurial, and erratic nature. He experienced moments of self-doubt and fear, but he was by no means cowardly. Rather, his deep understanding of the various possibilities often resulted in hesitation as he sought to select the best course of action. It was as if he could envision different outcomes, which sometimes overwhelmed his ability to move forward confidently. In conversations with a friend, Sherman compared himself to Ulysses S. Grant, noting that he was more nervous and prone to changing orders or countermarching his command.

Sherman had valid reasons to harbor a fear of failure. He had endured significant personal losses and experienced a sense of abandonment. Just as he had found success and a peaceful environment at the Louisiana Military Academy, the onset of the Civil War disrupted his newfound stability. During the war, Sherman suffered a mental breakdown due to the strain of command. He became convinced that massive Confederate forces were amassing against him. The press labeled him as “crazy,” and his wife expressed concerns about the “mental problems” that ran in the Sherman family. Consequently, he was temporarily relieved of his command and sent back home to Ohio to rest and recover.

While Sherman’s military career had not been without its successes, he faced a challenging time when he contemplated suicide. However, it is important to note that he was not truly “crazy” but was instead grappling with an episode of depression and anxiety. From this low point, Sherman would emerge stronger than ever before. He eventually found his place—a role that allowed his personality and abilities to thrive. Whether it was due to his better command of himself or simply the fact that Sherman needed an organized military leader to follow remains unclear. However, Sherman ultimately found that leader in General Ulysses S. Grant.

SHERMAN UNDERSTOOD WAR

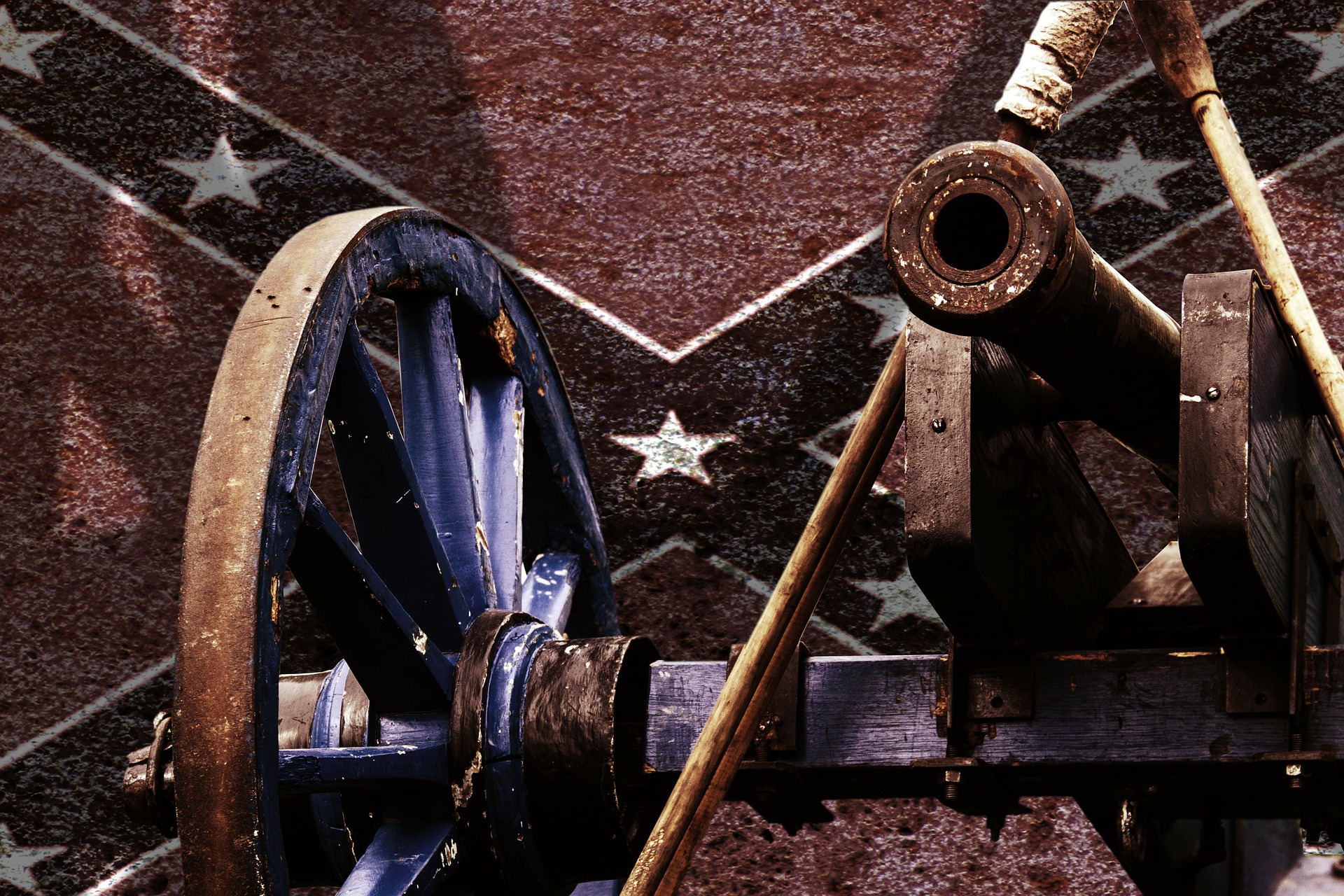

General Grant held Sherman in high regard, considering him one of his finest subordinates. Sherman’s true calling became evident as he fought alongside Grant in pivotal battles such as Shiloh, Corinth, and Vicksburg. In 1864, when Grant was called away for other duties, Sherman assumed command once again. His mission was to lead an army and launch an attack on Atlanta, which ultimately evolved into what is famously known as Sherman’s “march to the sea.”

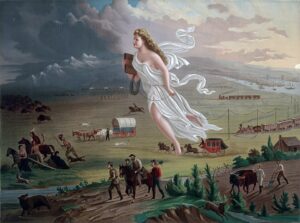

At West Point, Sherman’s philosophical approach to war began to take shape. He delved into James Kent’s “Commentaries on American Law,” which posited that war dissolved moral constraints and became a conflict between the entire populations of two nations. Sherman wholeheartedly grasped this concept and proceeded to carve a path through Georgia, stretching 60 miles wide, all the way to Savannah. Arriving in Savannah, he then led his forces north through the Carolinas to rendezvous with Grant and dismantle the Confederate army.

Sherman instructed his troops to “forage liberally on the country,” and they did just that. The soldiers obtained provisions and resources from the surrounding areas as they advanced, implementing a strategy known as “living off the land.” This approach aimed to disrupt the enemy’s supply lines while providing sustenance for Sherman’s forces.

The audacious campaign led by Sherman showcased his strategic brilliance and his willingness to employ unconventional methods to achieve victory. By adhering to the philosophy that war unleashed a different set of rules, Sherman charted a path that would leave an indelible mark on the history of the American Civil War.

Sherman possessed a deep understanding that defeating the enemy required more than simply overcoming their army. His own personal losses had given him a profound grasp of the realities of life and the importance of maintaining order and respect for authority. He recognized that the war would only come to an end when the enemy lost the will to fight. Sherman’s approach focused on attacking the “mind of the South,” recognizing that breaking the spirit and determination of the enemy was crucial to achieving victory. This perspective positioned him as a remarkably modern leader, earning him the reputation of being the most modern general of his time.

Beyond traditional battle plans and ground strategies, Sherman comprehended that the societal will to fight was the driving force behind an adversary’s strength. Thus, to win the war, it was essential to undermine and destroy that will, effectively securing victory without engaging in direct battle. He firmly believed that war was inherently cruel and could not be refined or made less brutal. “War is cruelty,” he said, “and you cannot refine it.”

“I am tired and sick of war. Its glory is all moonshine. It is only those who have neither fired a shot nor heard the shrieks and groans of the wounded who cry aloud for blood, for vengeance, for desolation. War is hell.”

– William Tecumseh Sherman

Not All the Soldiers Obeyed Orders

While acknowledging the inherent cruelty of war, Sherman made efforts to mitigate this cruelty whenever possible. In his Special Field Order No. 120, he instructed his troops to “forage liberally on the country during the march.” In cases where his army encountered attacks or hindrances, Sherman ordered the implementation of a “relentless” devastation on certain infrastructure, such as bridges and mills. It is important to note that these orders specifically prohibited soldiers from entering dwellings and from using threatening or abusive language toward civilians. Furthermore, the order emphasized the necessity of leaving behind sufficient supplies for the local population.

The majority of soldiers complied with these instructions, demonstrating a level of restraint and respect toward the civilian population. However, some individuals within Sherman’s army indeed engaged in looting and plundering, disregarding the orders and causing harm to the Confederate populace.

Sherman’s intentions were to conduct a strategic campaign that disrupted the enemy’s infrastructure and resources while minimizing direct harm to civilians. However, the execution of his orders was not uniform, and the actions of a minority tarnished the overall adherence to these guidelines. Recognizing this complexity and the range of behaviors soldiers exhibit during the conflict is essential.

Overall, Sherman’s march destroyed the ability of the South to fight back on a fundamental level. Sherman had divided his troops into two groups, and the Confederate leadership was confused about where the Union troops would attack. Sherman’s army destroyed the ability of the industry of the South to transport goods by destroying railroads. In some cases, Union troops burned whole towns to the ground. Those who disobeyed Sherman’s orders regarding how to treat civilians took their psychological toll on the Confederate people, and there were significant back-and-forth threats to kill prisoners on either side by both Confederate and Union leadership.

Sherman’s march took around seven weeks to complete and successfully freed up to a possible 25000 enslaved people held by the South. The Union campaign devastated the South in almost every way, and in April of 1865, Robert E Lee surrendered the Confederate cause.

To this day, the echoes of anger reverberate through the hearts of those who witnessed the Union’s relentless advance and Sherman’s fateful march to the sea. For those who stood helplessly, watching their homes engulfed in flames and their cherished livelihoods reduced to ashes, the wounds of betrayal and loss run deep. The bitter memories of citizens assaulted by Union troops, their cries echoing through time, have passed down a profound rage that lingers in the annals of history.

Sherman, the enigmatic figure at the center of this turmoil, became a symbol of both fear and reverence. In the South, he was branded a hated demon, the embodiment of all that was despised and resented. Yet, in the North, his name resonated with admiration and respect, etching his legacy as a renowned warrior who shaped a divided nation.

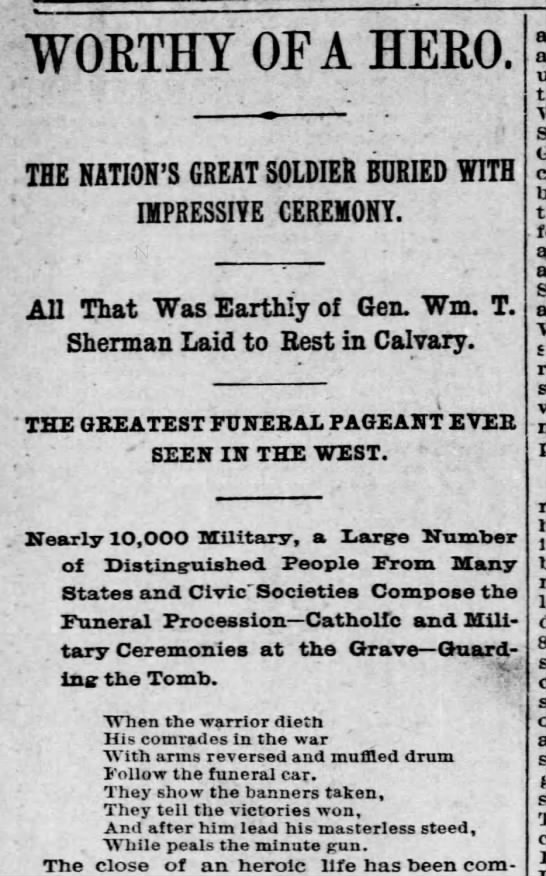

As the tides of war receded, Sherman would not rest on his laurels. Rising to prominence, he assumed the mantle of Commanding General of the United States Army, his formidable leadership recognized and celebrated. Despite the whispers and suggestions that he should ascend to the pinnacle of political power, Sherman rejected the allure of the presidency, forever committed to his role as a guardian of the nation’s defense.

Conclusion

In the twilight of his life, Sherman breathed his last in New York City in 1891, the metropolis serving as a backdrop to the final chapter of a man who had witnessed the unfathomable depths of conflict. His passing marked the end of an era, but the memories, the scars, and the lingering enmity are indicative of those tumultuous times.

Sherman’s march left an unerasable imprint on history like a tempest that forever altered the landscape. The stories and legends of those affected, their tales of sorrow and resilience, continue to captivate our collective imagination, reminding us of the complex tapestry of humanity in times of war and the enduring echoes of its aftermath.

Bibliography

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. “[Maj. Gen. Willam T. Sherman, Officer of the Federal Army].” Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/resource/cwpbh.00854/.

Hudson, Myles. “Sherman’s March to the Sea | Significance, Casualties, Map, Dates, & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, November 8, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Shermans-March-to-the-Sea.

Katcher, Philip R. The Civil War; Day by Day. New York, NY: Chartwell Books, 2010.

Marszalek, John F. Sherman: A Soldiers Passion for Order. 1St Vintage Civil War library ed. New York, NY: Vintage Civil War Library, 1994.

Tebeau, Charlton W. “William Tecumseh Sherman – Later Life | Britannica.” In Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Tecumseh-Sherman/Later-life.

The American Battlefield Trust. “William T. Sherman.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/william-t-sherman#:~:text=After%20the%20war%2C%20Sherman%20remained%20in%20the%20military.

ehistory.osu.edu. “War of the Rebellion: Serial 079 Page 0714 KY., SW. VA., TENN., MISS., ALA., and N. GA. Chapter LI. | EHISTORY.” Accessed August 22, 2022. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/079/0714.

Notable-quotes.com. “War Quotes,” 2019. http://www.notable-quotes.com/w/war_quotes.html.

Weigley, Russell Frank. A Great Civil War : A Military and Political History; 1861-1865. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Wiliams, Harry T. Mcclellan, Sherman, and Grant. 1St Elephant paperback ed. Chicago, 1991.