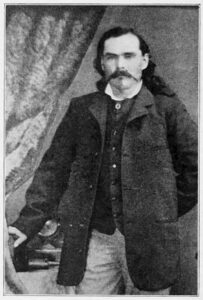

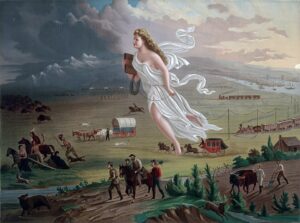

"American Progress", John Gast, 1872, oil on canvas

Manifest Destiny: Ideology of a Westward Nation

In the 19th century, many Americans came to believe it was their nation’s “manifest destiny” to expand across the North American continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The term was coined in 1845 by journalist John L. O’Sullivan, who urged the annexation of Texas and proclaimed it America’s “manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions”. This conviction blended a sense of divine mission with republican idealism – the notion that the United States was destined to bring democracy, Protestant Christianity, and “civilization” to the west. Such rhetoric imbued expansion with an almost religious zeal. The novelist Herman Melville captured this spirit when he wrote, “We Americans are the peculiar, chosen people – the Israel of our time”, suggesting that the nation saw itself as specially appointed to expand and lead.

This ideology had profound consequences. Advocates of Manifest Destiny used it to justify aggressive policies – from the removal of Native Americans to war with Mexico – in the name of national progress. “Providence is with us,” O’Sullivan declared, “and no earthly power can [stop] our onward march”. At the same time, the dream of a continental nation inspired thousands of ordinary Americans – farmers, pioneers, and missionaries – to pack up their lives and head west in search of opportunity. “The expansive future is our arena,” O’Sullivan wrote, encouraging Americans to look to “untrodden space” in the West as a new frontier of hope. This narrative will trace how that grand ambition unfolded on the ground: through land deals and political battles, wagon trains and railroads, homesteads and boomtowns, and conflicts that forever changed the lives of diverse peoples, including white settlers, Native Americans, African Americans, immigrants, soldiers, and others. The story of Westward Expansion is one of bold ventures and brutal dispossession – a “great nation of futurity,” in O’Sullivan’s words, built on both lofty ideals and devastating human costs.

Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase and Early Expansion (1803–1820s)

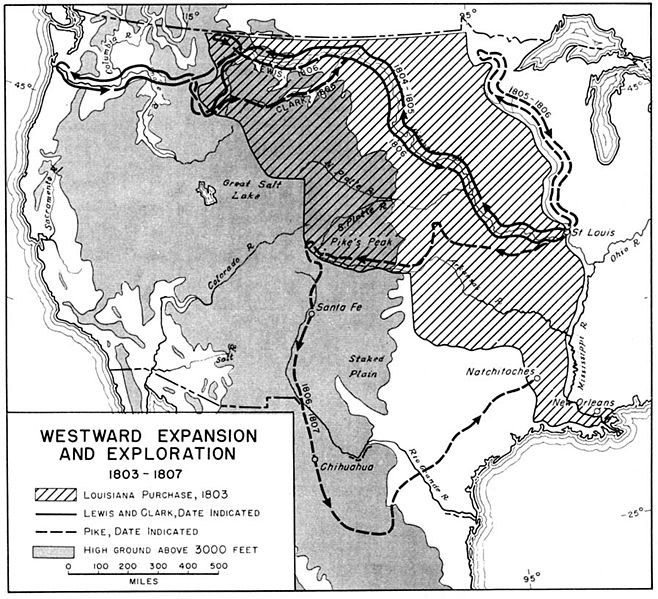

The push west began in earnest under President Thomas Jefferson. In 1803, Jefferson seized a sudden opportunity to double the nation’s size by purchasing the vast Louisiana Territory from France. This Louisiana Purchase added some 828,000 square miles west of the Mississippi River – from New Orleans up through the Great Plains – to the United States. Jefferson envisioned this new land as an “empire for liberty,” a boundless expanse that could “absorb the flood of Americans westward for many generations”, securing enough farmland for the nation’s agrarian future. Yet the acquisition also raised complex questions. The U.S. had obtained a territory populated by around 50,000 French and Spanish colonists, free blacks and slaves, and countless Indigenous peoples. How would these people be incorporated, and what did American expansion mean for the Native American tribes who already inhabited the West?

Jefferson believed Native Americans would have to give way to American settlement – even if that meant relocating them. In an 1803 letter to John Breckinridge, he proposed using Louisiana as a new Indian domain: “The best use we can make of the country,” Jefferson wrote, “will be to give establishments in it to the Indians on the east side of the Mississippi, in exchange for their present country”, thereby opening up ancestral Native lands in the East for white settlers. This laid the groundwork for a policy of Indian removal that would intensify in coming decades. Jefferson’s vision, though couched in paternalistic language, foreshadowed a tragic aspect of westward expansion – the coercion and exile of indigenous nations to make room for the “onward march” of the United States.

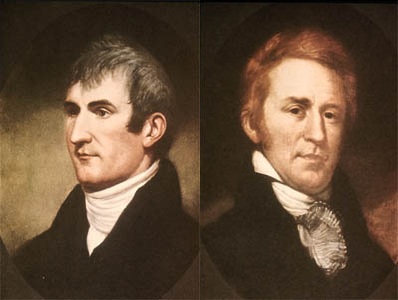

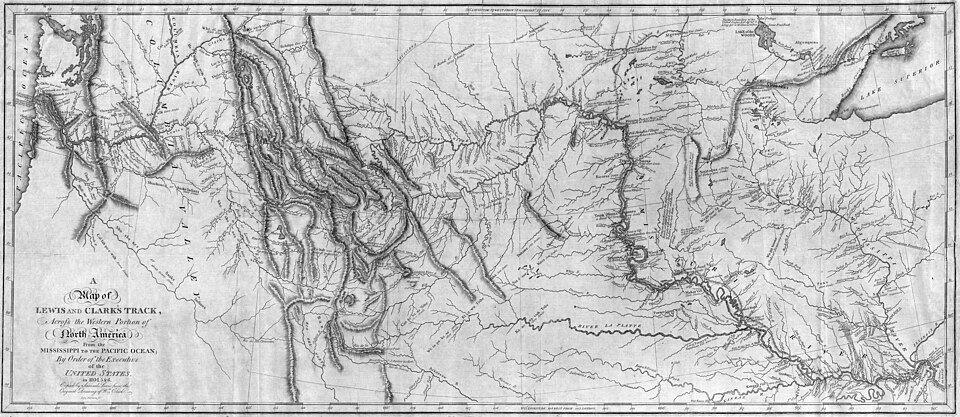

Meanwhile, the Louisiana Purchase spurred exploration. Jefferson sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on their famous 1804–1806 expedition to survey the new territory all the way to the Pacific. Their journey revealed the rich resources of the West – vast prairies teeming with bison, great mountain ranges, and networks of indigenous trade. Reports of fertile lands beyond the Mississippi tantalized American farmers. In the following years, a trickle of frontiersmen, trappers, and traders ventured west. By the 1810s and 1820s, new states like Louisiana, Missouri, and Arkansas entered the Union as cotton plantations spread into former French and Spanish areas. Each step west kindled Americans’ appetite for more land. President James Monroe in 1823 declared the Western Hemisphere off-limits to new European colonization (the Monroe Doctrine), reflecting rising confidence that the continent was America’s to dominate. The sense of a special destiny only grew stronger with time.

Trail of Tears: The Forced Removal of Native Americans (1830s)

As white settlers pressed west and south in the early 19th century, they increasingly came into conflict with Native American nations, especially in the Southeast. Powerful tribes like the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole had long occupied fertile lands in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida – lands coveted by cotton planters. Under President Andrew Jackson, the U.S. government adopted an explicit policy to uproot these tribes and relocate them beyond the Mississippi River. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 authorized the forced relocation of Eastern tribes to “Indian Territory” in the West (present-day Oklahoma). What followed was one of the darkest chapters of westward expansion: the Trail of Tears.

Despite legal efforts by the Cherokee to resist – they famously won a Supreme Court case in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), which affirmed their sovereign rights – Jackson defied the court and pressed ahead with removal. In late 1838, the U.S. Army began rounding up Cherokee families at gunpoint. Some 16,000 Cherokee were driven from their homes and forced to march roughly 1,000 miles westward during the winter. Thousands died from cold, hunger, and disease on this Trail of Tears. Chief John Ross of the Cherokee Nation, who had vainly petitioned Congress to stop the removal, described the cruel injustice in a memorial letter: “By the stipulations of [the removal treaty], we are despoiled of our private possessions… We are stripped of every attribute of freedom…. Our property may be plundered before our eyes; violence may be committed on our persons; even our lives may be taken away, and there is none to regard our complaints. We are denationalized; we are disenfranchised. We are deprived of membership in the human family! We have neither land nor home, nor resting place that can be called our own.” Ross ended his protest with a poignant cry: “We are overwhelmed! Our hearts are sickened… when we reflect on the condition in which we are placed”. His words capture the anguish of a people uprooted by greed and broken promises.

By the 1840s, the U.S. had forcibly removed tens of thousands of Native Americans from the East – not only the Cherokee but also Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole and others – into the distant lands west of Arkansas and Missouri. The newly cleared lands were quickly occupied by white settlers and slave plantations. Though often justified as a benevolent policy to “save” Native peoples from extinction, removal in reality inflicted immense suffering. Entire nations were decimated and cultural connections to ancestral lands severed forever. Yet even as one tragic phase of expansion unfolded in the Southeast, a new wave of voluntary migration was beginning along the far trails to the Great West.

Pioneers Forge New Trails to the West (1840s)

By the 1840s, the promise of wide-open land in the West was drawing growing numbers of pioneers from the United States and abroad. The most famous route was the Oregon Trail, a 2,000-mile wagon road that ran from the Missouri River, over the Rockies, to the fertile valleys of Oregon Country (in the Pacific Northwest). What began in the 1830s as an arduous trek undertaken by a few missionaries and fur traders had, by the mid-1840s, grown into a veritable flood of wagon trains. Entire families packed their belongings into covered wagons, forming long wagon caravans that snaked across plains and mountain passes in search of new homes. By 1860, hundreds of thousands of Americans had migrated west via the overland trails, despite the great dangers and difficulties. Contemporary observers described the Oregon Trail as an “army of emigrants” on the march.

A 19th-century style covered wagon, the quintessential vehicle of pioneer journeys west. Wagon trains of this type carried families and all their belongings across the prairies and over the Rockies on trails like the Oregon Trail.

Importantly, these emigrants were not only hardy frontiersmen but also women and children. In fact, the presence of women in the overland caravans helped dispel the notion back East that the West was an uninhabitable “howling wilderness.” One early pioneer woman, Narcissa Prentiss Whitman, proved this point dramatically. In 1836 Narcissa and her husband became among the first white women to cross the Rocky Mountains. “Despite the travails of the journey, Narcissa thrived,” an account noted. She wrote enthusiastic letters from along the trail describing how “rivers were fordable, travel by wagon was practical, and the so-called hostiles were generally friendly.” Her letters were published in Eastern newspapers, encouraging others to follow. Narcissa Whitman’s own journal gives a vivid picture of trail life. She described nights camped on the Platte River where fuel was so scarce the party cooked meals over “dried buffalo dung” serving as makeshift coal. Yet she remained upbeat: “Our manner of living is far preferable to any in the States,” Narcissa wrote to her family from the prairies. “I never was so contented and happy before”. Rising at dawn to the cries of “Arise! Arise!” and the braying of mules, her wagon company traveled in a great column – “really a moving village” of men, animals and wagons stretching across the plains. At night they encamped in a circle with livestock corralled inside, ever wary of horse thieves or attacks. Narcissa noted that constant guard was kept “to protect our animals from the approach of Indians, who would steal them”, though she also encountered Native peoples curiously but peacefully observing the wagon train.

If Whitman’s letters showed an almost romantic view of the overland journey, other pioneers recorded the hardships and hazards in stark detail. Amelia Stewart Knight, who trekked the Oregon Trail in 1853 with her husband and seven children (while pregnant with an eighth), kept a diary of daily life on the trail. Her entries speak to the exhaustion, bad weather, and constant concern for safety. “Made our beds down in the tent in the wet and mud…Cold and cloudy this morning, and everybody out of humor,” Amelia wrote in April 1853. The trail turned into a quagmire after rains, wagons broke down, oxen went lame. “One of our best oxen is too lame to travel…We have to yoke up our muley cow in the ox’s place,” she recorded, noting grimly the road was “strewn with dead cattle, and the stench is awful”. Crossing rivers was especially perilous: “Three hundred or more wagons in sight” waiting to ferry across, she wrote, and improvised rafts had to be made by floating wagon beds. Amelia described one crossing where a man in a wagon train ahead “had drowned a few days before, in a river called Elkhorn…his wife was lying in the wagon quite sick, and children were mourning for a father gone”. Death was a frequent traveler on the trail – from drowning, accidents, and above all disease (cholera outbreaks could wipe out whole groups of emigrants). Amelia Knight noted that “perhaps 30,000 [people] perished en route” out of the hundreds of thousands who attempted the overland journey.

Encounters with Native Americans along the trail were a source of both fear and fascination for pioneers. Early in her journey, Amelia Knight’s children were terrified at the first sight of Indians: “Saw the first Indians today. Lucy and Almira [her daughters] afraid and run into the wagon to hide,” she wrote. Yet as the weeks went on, they grew accustomed to seeing indigenous people. Amelia noted that local tribes often approached the camps “begging money and something to eat. Children are getting used to them,” she observed in her diary. Sometimes relations were friendly – her party traded for fresh salmon with Indians in the Grand Ronde Valley, a welcome treat after long months of salted provisions. Other times there was tension and violence. Near Rock Creek in what is now Idaho, Amelia recorded that “Indians are so troublesome” there that emigrants posted guards all night; a man ahead of them “had all his horses stolen”, and every year, she noted, settlers were killed in that area. On one frightening night, she lay awake expecting an attack, “very much frightened…every minute we would be killed”, though by morning “we all found our scalps on”. Such accounts reveal the complex reality of contact on the trails – moments of genuine exchange and help, as well as mutual fear stoked by cultural misunderstanding and competition for resources.

By the mid-1840s, the trickle of pioneers had become a torrent. Whole communities moved west. Wagon traffic was so heavy on the Oregon Trail that one traveler in 1849 wrote, “As far as the eye can reach, the bottom is covered…with cattle and horses” waiting to cross a river. That same year, over 25,000 Americans – the single largest wagon migration ever – headed to Oregon and California. This mass overland migration all but overwhelmed British claims in the Pacific Northwest. In 1846, President James K. Polk, an ardent expansionist, negotiated a treaty with Britain to divide the Oregon Country at the 49th parallel, peacefully securing today’s Oregon, Washington, and Idaho for the U.S.. The great Oregon migration thus achieved by settlement what diplomacy alone might not have – fulfilling American aims in the Northwest without a war. But even as Polk compromised with Britain in Oregon, he was gearing up for a far more aggressive expansion to the south and west, driven by the same vision of Manifest Destiny.

“Manifest Destiny” in Action: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War (1840s)

Nowhere was the ethos of Manifest Destiny more influential than in Texas and the Southwest. The Mexican Republic, independent from Spain since 1821, still controlled an enormous territory north of the Rio Grande in the 1830s – what is now Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. In the 1820s, Mexico had invited American settlers into the sparsely populated province of Tejas (Texas). But cultural and political conflicts led Texan colonists (many of them slave-owning Americans) to rebel against Mexico. After winning the famous Battle of the Alamo and subsequent victory at San Jacinto, the Texans established an independent Republic of Texas in 1836. For nearly a decade Texas remained its own country, albeit one largely populated and governed by American-born settlers. Many in the U.S. eagerly sought Texas’s annexation, seeing it as the next logical piece of America’s continental puzzle. Others were wary, since adding Texas – a large slave-holding territory – would ignite sectional disputes over slavery’s expansion. By the mid-1840s, however, expansionist sentiment was at a fever pitch.

When pro-annexation James K. Polk won the U.S. presidency in 1844, he took O’Sullivan’s words to heart. The term “Manifest Destiny” itself gained wide currency that year, as O’Sullivan wrote that it was “the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence” – a rallying cry for those who wanted to bring Texas (and more) into the Union. In 1845, the United States annexed Texas, admitting it as a new state. The proud Texas Republic flag was lowered, and the Stars and Stripes rose over Austin. But the annexation infuriated Mexico, which had never recognized Texan independence and still claimed the land. A dispute soon broke out over the new Texas-U.S. border – whether it lay at the Nueces River or the more southerly Rio Grande. Polk, a zealous expansionist, was not content with Texas alone. He had designs on Mexico’s California and New Mexico territories as well. In 1846, when a skirmish between U.S. and Mexican troops occurred in the disputed border zone, Polk seized the moment to ask Congress for a declaration of war, famously asserting, “American blood has been shed on American soil.” The Mexican–American War had begun.

The war (1846–1848) was a direct product of Manifest Destiny fervor – a land grab couched in terms of national honor and racial destiny. Volunteer regiments of enthusiastic young men from across the United States flocked to fight, lured by the romance of battle and the prospect of new western lands. Yet not everyone was convinced the war was just. A young U.S. Army officer, Ulysses S. Grant, went off to fight in Mexico with ambivalence. With hindsight, Grant – who would later lead Union forces in the Civil War – harshly condemned the conflict. “For myself, I was bitterly opposed to the measure,” Grant wrote, “and to this day regard the war… as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.” In his memoirs he lamented that “the wickedness was not in the way our soldiers conducted it, but in the conduct of our government in declaring war.” Grant’s perspective underscores that not all Americans saw Manifest Destiny as a moral good – some recognized it as aggressive expansion at others’ expense. Indeed, critics like Congressman Abraham Lincoln and writer Henry David Thoreau spoke out against the war at the time, viewing it as an unjust invasion of a neighbor’s land to expand slavery.

Nonetheless, American arms triumphed decisively. U.S. forces invaded Mexican territory on multiple fronts, and by September 1847 they had captured Mexico’s capital, Mexico City. In the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico was forced to cede an astonishing amount of territory – over half its land – to the United States. This Mexican Cession included present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming. Combined with the Oregon Territory settlement and the earlier Louisiana Purchase, the United States now stretched from sea to sea. The dream of a continental republic had been realized on the map. Less acknowledged was the human cost: thousands died in battle, and Mexican civilians suffered greatly; the war also reopened fierce debates about slavery (whether new territories would be slave or free) that pushed the nation toward internal conflict.

For Mexicans and many Native Americans in the ceded lands, the end of the war marked the beginning of a new struggle. They suddenly found themselves living under American jurisdiction, often treated as foreigners on their own soil. The Californios (Mexican Californians) and Tejanos (Mexican Texans) lost political power and, over time, much of their land to incoming Anglo settlers. But in the immediate aftermath of 1848, another development would utterly transform the newly acquired western lands and hasten the onrush of American settlers: the discovery of gold in California.

The California Gold Rush and the Rush for Wealth (1848–1850s)

In January 1848, just days before Mexico formally surrendered California, a carpenter working at Sutter’s Mill in the Sacramento Valley made a fateful discovery – flecks of gold in the river. News of the find spread slowly at first, but by late 1848 the secret was out: California had gold “in abundance.” By 1849, a frenzy known as the California Gold Rush was underway. Tens of thousands of fortune-seekers from around the United States (and indeed the world) dashed toward California, eager to strike it rich. These “Forty-Niners” came by any means available – some braved the long overland trail across the continent, while others sailed by ship, either around Cape Horn at the tip of South America or via the disease-ridden shortcut across the Panamanian isthmus. In 1849 alone, the non-native population of California exploded from perhaps 20,000 to over 100,000. San Francisco mushroomed from a sleepy village into a bustling boomtown filled with tents, saloons, and supply shops for miners. The Gold Rush was one of the most dramatic human migrations in history – a chaotic stampede that one observer called “the wildest event of its kind in the history of the world”.

For those who undertook the overland journey to California, it could be even more grueling than the Oregon Trail. Many Forty-Niners, mostly young men traveling in ox-drawn wagons, recorded scenes of hellish difficulty in the deserts and mountains. One emigrant letter described leaving the Humboldt River in the Nevada desert: “The road this day lay over a large plain of alkaline earth…We found the road strewn with dead and dying oxen, caused by want of grass and water…We arrived at some warm springs near the ‘Black Rock’ next morning at sunrise, leaving one ox on the road which we had been driving loose”. He went on to recount how in some boiling springs, travelers even “boiled rice by placing it in a small bucket which they set in [the hot] spring”, an improvised camp stove in the wilderness. As they neared the Sierra Nevada, many parties abandoned wagons and animals altogether in a desperate attempt to cross the snowy passes before winter. The final legs of the journey were littered with discarded supplies, broken wagons, and the graves of those who didn’t make it. “The chance of getting gold was a hundred times greater than the chance of getting back with it,” a newspaper quipped, “Yet these men turned their faces to the west…by foot and ox team, they trudged onward…with a frenzied cry for the spoils”. Such was the lure of gold – it drove people to risk everything.

When the weary gold-seekers reached California’s diggings, they found a rough-and-tumble world unlike anything they had known. The gold fields were a melting pot (and powder keg) of many races and nationalities. Along with Americans from every state, there were Mexican miners, Chinese laborers (who began arriving by ship in 1850), South American adventurers (Chileans, Peruvians), Europeans (French, German, Irish), and even a few Australians. Free African Americans and even some enslaved African-Americans (brought by Southern masters) were in the camps as well. All were scrambling for a share of the golden wealth. A letter from one ’49er describes the basic method of placer mining and gives a sober assessment of the work: “The gold is found on bars and in the bed of a river, which is laid dry by building dams and turning its course, and in crevices of rocks…There is gold in California and it will not be exhausted for many years, but those who want it must work and work hard. Now and then a man makes a lucky hit…but this is not done every day nor by every person.” In other words, the Gold Rush was not an endless bounty lying on the ground for the taking – it was mostly backbreaking labor, with long odds against striking it rich. Indeed, the ones who often profited most were not individual miners but merchants and companies that supplied the miners (shrewd businessmen like Samuel Brannan, who sold picks and pans, or Levi Strauss, who made durable canvas pants for miners).

Still, early on, the surface gold was so plentiful that ordinary folks did make striking finds. Miners could earn in a day what might take months back East – one contemporary noted “wages at mining are from an ounce ($16) to three ounces of gold a day”, astonishing pay for the time. Camps buzzed with rumors of rich strikes; whenever a big find was confirmed, a rush would ensue to that locale. Mining life was crude. Many camps were little more than canvas tents or shanties clustered along a creek. Sanitation was poor, prices for basic goods outrageous (miners might pay a dollar – a day’s wage back East – for a single onion or egg). Law and order barely existed at first; vigilante justice was common. Yet there was also an electric excitement in the air – a democratic spirit where birth and titles meant little and success went to the clever, the bold, or just the lucky. A miner’s letter from 1849 enclosed a small sample of gold dust for his family and remarked, “It then appears as you see in the sample I am enclosing. Divide it up among the neighbors.”[1] Such letters sent “back home” – often printed in local newspapers – further fanned the gold fever across the country.

The Gold Rush also had dark aspects. Indigenous Californians suffered terribly as miners and newly arriving settlers encroached on their lands; vigilante killings and disease decimated Native communities. Mexican and Chinese miners faced intense discrimination and violence from American rivals – California imposed a hefty foreign miners’ tax aimed especially at the thousands of hardworking Chinese laborers, and periodic anti-Chinese riots erupted. By the mid-1850s, many of the easy gold deposits were played out, and larger companies moved in to perform hydraulic mining (using high-pressure water to wash hillsides into sluices) which required capital and machinery beyond the means of lone prospectors. The era of the lone Forty-Niner with a pick and pan was relatively brief. But the Gold Rush had permanently transformed California. In 1850, California was admitted as a state – astonishingly fast growth for a territory that barely had 15,000 non-Natives in 1848. San Francisco, from which wealth flowed, became a booming metropolis. And the Gold Rush stamped the American imagination with enduring legends of frontier fortunes and pioneering adventure.

Crucially, the Gold Rush also accelerated other western expansions. The sudden need to reach California spurred calls for transcontinental transportation (ultimately leading to the Transcontinental Railroad, completed in 1869). It also drew more immigrants directly from overseas to the West Coast. And it raised anew the contentious question: would these new western territories be slave or free? That question would soon ignite in “Bleeding Kansas” and the sectional crisis of the 1850s.

Bleeding Kansas and the Sectional Crisis (1850s)

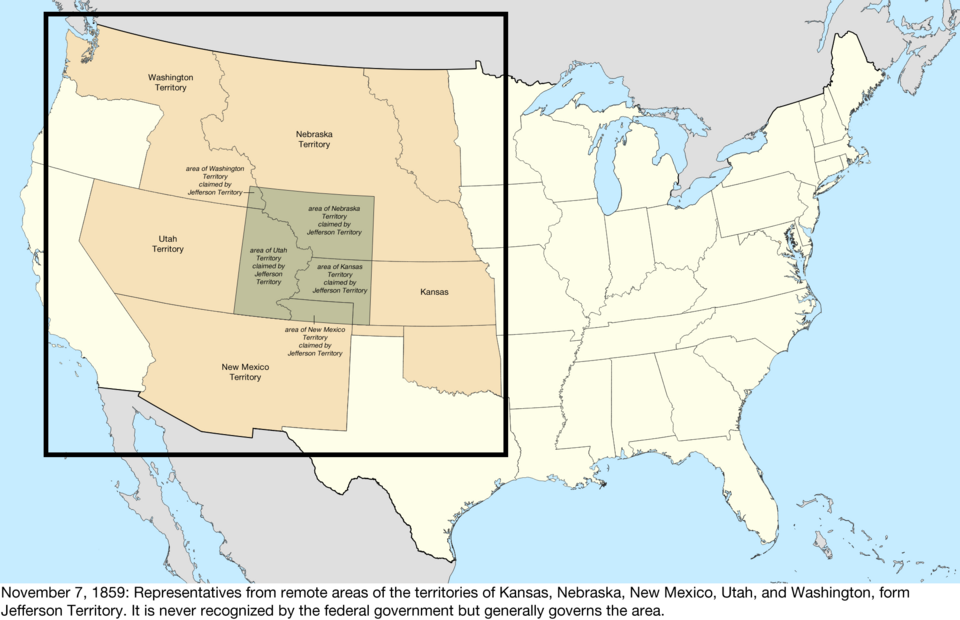

Westward expansion during the 19th century did not just involve settlers and covered wagons – it also dragged the country into the fierce political conflict over slavery. Every time the United States acquired new territory, the question arose: would slavery be allowed to expand into these lands? This issue came to a head in the 1850s over the Kansas and Nebraska territories, on the western frontier of Missouri and Iowa. The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, crafted by Senator Stephen Douglas, effectively repealed the old Missouri Compromise line and said settlers in Kansas Territory could vote to decide whether to allow slavery (the doctrine of “popular sovereignty”). This triggered a rush by both pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers into Kansas, each group trying to establish majority control. The result was an outbreak of violence so intense that the territory became known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

For several years (1855–1859), Kansas was a battleground of America’s divisions. Pro-slavery Missourians (sneeringly nicknamed “Border Ruffians”) crossed into Kansas to stuff ballot boxes and intimidate Free-Soil settlers. In response, Eastern abolitionist groups sent anti-slavery New Englanders west (the “Beecher’s Bibles” they carried were actually rifles). John Brown, a radical abolitionist, gained notoriety by leading a vengeful raid at Pottawatomie Creek in 1856, where his band killed five pro-slavery settlers in cold blood. Armed clashes and reprisals on both sides claimed dozens of lives. A Georgia newspaper described the chaos: “Civil war, in all its horrible aspects, is raging in Kansas. Towns are sacked and burnt. Peaceful inhabitants are murdered in cold blood…The roads are infested with armed robbers, and the torch of the incendiary is applied to every dwelling of the [anti-slavery] party”, an exaggerated but telling account of the anarchy. While Bleeding Kansas was a localized mini-war, it presaged the national cataclysm to come (the Civil War). It demonstrated that the issue of slavery’s expansion, tied directly to westward growth, had pushed the nation to the brink of disunion.

For African Americans, the stakes of westward expansion were enormous. Enslaved people were forced west as slaveholders moved into new territories like Texas and Kansas, extending the reach of bondage. At the same time, free blacks and abolitionists saw the West as a potential promise of freedom. Kansas, especially after it entered the Union as a free state in 1861, became a symbol of hope. Decades later, in the 1870s, former slaves would look to Kansas as a safe haven (the “Exoduster” movement, discussed below). One black emigrant from Louisiana explained his yearning for Kansas by invoking the memory of its antislavery struggle: “I am very anxious to reach your state,” he wrote to the Kansas governor in 1879, “not just because of the great race now made for it but because of the sacredness of her soil washed by the blood of humanitarians for the cause of black freedom.” The “sacred soil” of Kansas, where abolitionists like John Brown had fought and bled, represented to freedmen a chance for true liberty and land of their own. Thus, westward expansion had entwined with the fate of slavery and freedom: the frontier could be a place where slavery spread, or where freedom took root, depending on who won the battle for each new territory.

By 1860, the sectional crisis over slavery – fueled in no small part by these western disputes – split the nation. The election of Abraham Lincoln (from the anti-slavery Republican Party) triggered the secession of Southern states. The Civil War (1861–1865) engulfed the country, temporarily halting most westward migration as the Union fought to prevent disunion. But even during the Civil War, the federal government under Lincoln took bold steps to encourage expansion and shape the West’s future.

The Homestead Act and New Settlers of the Plains (1862–1870s)

In the midst of the Civil War, President Lincoln and Congress passed landmark legislation that would profoundly influence postwar westward expansion. One was the Homestead Act of 1862, which opened millions of acres of public land for settlement by ordinary citizens. Any adult citizen (or intended citizen) who had never taken up arms against the U.S. could claim 160 acres of federal land for free, provided they lived on it and improved it (built a dwelling and farmed) for five years. This Homestead Act was a democratic revolution in land policy – instead of selling western lands to the highest bidder or reserving them for the elite, the government essentially gave away the West in small parcels to encourage family farms. As a result, after the war, thousands of families, including many poor farmers and newly arrived immigrants, poured into the Great Plains and Midwest to “prove up” homesteads. By one estimate, the Homestead Act and related laws eventually transferred some 270 million acres of land to individuals, truly transforming the prairie into an American heartland of farms and communities.

Among those who seized the Homestead Act’s opportunity were groups formerly excluded from the American promise. Freed African Americans in particular saw the West as a land of opportunity after Emancipation. Though few freedmen had the resources to move during Reconstruction, a grassroots migration of Southern black families to Kansas began in the late 1870s. These migrants, known as Exodusters, likened their journey to the biblical exodus from slavery in Egypt to the Promised Land. In 1879, over 6,000 black refugees from the Deep South arrived in Kansas, fleeing rampant violence and discrimination in the post-Reconstruction South. One Louisianan wrote to Kansas Governor John St. John expressing his hope: “The Homestead Act and other liberal land laws offer us the opportunity to escape the oppression of the South and become owners of our own farms. For people who have spent their lives working the lands of white masters with no freedom or pay, such opportunities seem the answer to a prayer.” By heading west, these African Americans sought not just land but dignity. As noted, one migrant movingly described Kansas soil as hallowed by the blood of abolitionist martyrs – a place where black freedom had been fought for and thus a place it could flourish. Despite harsh conditions and initial destitution (many Exodusters arrived almost penniless and required aid from relief organizations), they established enduring black farming settlements in Kansas and neighboring states. The West thus became a new frontier of African-American hope, even as they faced ongoing racial prejudice there too.

The vast open plains also beckoned to European immigrants in search of land. In the decades after 1865, a stream of immigrants from Germany, Scandinavia (Sweden, Norway, Denmark), and other parts of Europe flowed into America’s midsection. Railroads and state agencies aggressively advertised western lands in Europe, promising cheap or free farms to those willing to emigrate. By the 1870s, Minnesota, Nebraska, Kansas, and the Dakotas had significant immigrant populations. (For example, by 1870, nearly 75% of Swedish immigrants in America lived in the Midwest and Plains states.) These newcomers founded towns with names like Stockholm (Nebraska) or New Ulm (Minnesota), preserving elements of their Old World culture on the prairies. One Swedish homesteader’s letters from Kansas in the 1870s describe both hardship and determination: the struggle to build a sod house before winter, the swarms of grasshoppers that devoured crops, but also the joy of owning land and the hope that “this wide prairie will feed our children in years to come.” Many immigrants formed tight-knit rural communities – German Volga Russians farming the Kansas plains with Turkey Red wheat, Norwegians populating the Dakota Territories – giving parts of the West a distinctly multicultural patchwork. The Homestead Act did not discriminate by race or origin (in theory); even single women could claim land in their own name. Thus the West in the late 19th century saw an unprecedented diversity of small farmers and ranchers putting down roots.

Life for these homesteaders was challenging. The Plains were a land of extremes – scorching summers, bitter winters, droughts and blizzards, and occasional locust plagues. Trees were scarce, so many early settlers built sod houses cut from the prairie turf. One famous photograph from Nebraska in the 1880s shows a proud pioneer family posed in front of their sod house, a low, grass-roofed dugout structure, the very picture of frontier tenacity. They endured isolation (nearest neighbors might be miles away), and farm work was unending. Yet the prairies had an austere beauty and offered something priceless: independence. A homesteader who persevered for five years could receive a patent, making the land his or her private property. By sheer toil, families literally “earned” their 160 acres, acre by acre. The expanding web of railroads helped, too – by the 1880s, rail lines crisscrossed Kansas, Nebraska, and beyond, enabling farmers to ship their wheat or corn to national markets and to receive goods (lumber, farm tools, sewing machines) that tied them into a growing economy.

Not all western land was free for the taking, of course. Much had to be wrested from Native Americans who still inhabited the Plains in large numbers. During the Civil War, conflicts with tribes such as the Dakota Sioux and the Cheyenne had already flared. After the war, as homesteaders and ranchers flooded the plains and mountains, the U.S. government pursued a policy confining tribes to reservations – often by force. The stage was set for the Plains Indian Wars of the 1860s–1880s. As settlers planted farms and cattle ranches on the land, and as the precious buffalo herds were wantonly slaughtered, the indigenous peoples of the plains (Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, Comanche, Nez Perce, Apache, and others) made a last stand to defend their territory and way of life.

The Iron Road: The Transcontinental Railroad (1863–1869)

Even as homesteaders were plowing the prairie, industrial innovation was binding the West to the rest of the nation. The greatest infrastructure project of the age was the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad. Authorized by Congress in 1862, construction began during the Civil War and accelerated afterward. Two railroad companies, the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific, built from opposite ends – the Union Pacific westward from Omaha, Nebraska, and the Central Pacific eastward from Sacramento, California – aiming to meet in the middle. For six arduous years, crews labored on the “iron road” that would unite East and West by rail, something long dreamed of by visionaries. On May 10, 1869, they met at Promontory Summit, Utah, driving a ceremonial golden spike to complete the line. At that moment, one could travel from New York to San Francisco in a week instead of six months – the continent had effectively shrunk, and the frontier would never be the same.

The building of the railroad was itself an epic saga, involving remarkable feats of engineering and labor. The Union Pacific crews, working across the flat plains and blasting through the Rockies, were composed largely of Irish immigrants and Civil War veteran laborers. The Central Pacific, which faced the far more daunting task of carving a rail line through the granite peaks of the Sierra Nevada, relied on the toil of Chinese immigrant laborers. The contribution of the Chinese workers was immense – and for many years underappreciated. Initially, the railroad’s managers doubted if Chinese men (often derided then as “Celestials”) could handle the heavy work of laying track and tunneling. But Central Pacific’s Charles Crocker famously retorted, “Didn’t they build the Chinese Wall?,” pointing out that Chinese laborers had proven their mettle in difficult projects[2]. Indeed, the railroad quickly found the Chinese workers indispensable. By 1867, about 12,000 Chinese men were working on the Central Pacific – roughly 80% of its workforce. They labored from dawn to dusk, drilling and blasting tunnels through solid rock, often hanging from ropes on cliff faces to place explosives. In winter they faced horrific conditions: the Sierra snows were so deep (up to 12 feet) that they worked in snow tunnels beneath the drifts, at constant risk of avalanches. Their work ethic impressed many. As one company official wrote, “We have proved their value as laborers & everybody is trying Chinese [workers]; now we can’t get them [in sufficient numbers].” In June 1867, thousands of Chinese railroad workers even staged a landmark strike, demanding higher wages and shorter hours. Charles Crocker, the construction superintendent, refused to negotiate – he starved them out by cutting off food deliveries. But he later admitted that the nonviolent discipline of the Chinese strikers won his grudging respect: “If there had been that number of white laborers…it would have been impossible to control them. But this strike of the Chinese was just like Sunday…No violence was perpetrated along the whole line.” The railroad was completed, in large part, on the backs of these Chinese immigrants who received little glory at the time. (Tellingly, in the famous 1869 photograph at Promontory Summit of the rail crews celebrating, none of the Chinese workers were identified – a reflection of the era’s prejudice.)

When the final spikes were driven at Promontory, telegraph wires flashed the single word “DONE” to cities across the nation. Cannon boomed in New York, and San Francisco threw a jubilant parade. The Transcontinental Railroad was hailed as the consummation of Manifest Destiny – “railroaded” proof that American ingenuity and ambition had tamed the wilderness. It had immediate effects: travel time and cost plummeted, accelerating western settlement. Farmers and ranchers could ship goods to distant markets; mail and news moved at lightning speed. The railroad also radically changed the environment and Native American life. It bifurcated the vast buffalo ranges, and professional hunters (often riding the trains) slaughtered the buffalo by the millions to feed railroad crews or for sport. The bison – a cornerstone of Plains tribes’ existence – nearly went extinct by 1883, which dealt a deathblow to the independence of many nomadic tribes. Railroad companies, granted millions of acres of land around their tracks, energetically sold off that land to settlers and land speculators, further populating the West. Towns sprang up along the rail lines like beads on a string. In short, the iron horse bound the West to the rest of the Union, both economically and symbolically. As one newspaper proclaimed in 1869, the transcontinental link meant “the unity of our Country” was assured, just four years after a war had nearly torn it apart.

Celebration of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah. In this famous photograph by Andrew J. Russell, workers of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads meet and toast with champagne as their locomotives (“Jupiter” on left and Union Pacific No. 119 on right) face each other. The event marked the coast-to-coast unification of the U.S. by rail.

Native Resistance and the Closing of the Frontier (1870s–1890)

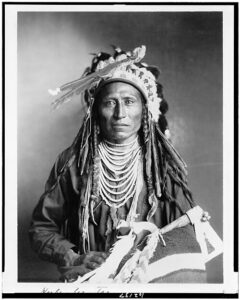

With the continental rails laid and settlers flooding into the Plains and Pacific Coast, by the 1870s the United States had largely fulfilled its territorial Manifest Destiny. But this victory for American expansion spelled catastrophe for the Native American nations of the West. The final chapters of westward expansion were dominated by the Indian Wars on the Great Plains and in the Southwest, as well as the imposition of the reservation system. From the late 1860s through the late 1880s, the U.S. military engaged in a series of fierce conflicts with various tribes that resisted confinement and fought to preserve their lands. These conflicts have become legendary – and infamous – in American memory: Red Cloud’s War (Lakota and Cheyenne vs. U.S. Army, 1866–68), which ended in a rare Native victory and the temporary closure of the Bozeman Trail; the Modoc War in California (1872–73); the Great Sioux War (1876–77) culminating in the Battle of the Little Bighorn; the Nez Perce War (1877); and the prolonged campaigns against Apache leaders like Geronimo in the Southwest (1870s–1880s).

One of the flashpoints was the Black Hills of Dakota Territory. Though the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 had guaranteed the sacred Black Hills to the Lakota “for their perpetual occupancy”, as soon as gold was discovered there in 1874, miners poured in and the U.S. government moved to take the hills back[3][4]. This betrayal exemplified the U.S. approach to treaties: they were kept only until the land or resources they covered became desirable. Red Cloud, the Oglala Lakota chief who had fought the U.S. to a standstill earlier, traveled to Washington in 1875 to plead that Americans honor their promises. It was in his old age, after seeing treaty after treaty broken, that Red Cloud gave his famously bitter assessment: “They made us many promises, more than I can remember. But they kept but one – They promised to take our land…and they took it.”[2] This stark quote encapsulates the experience of countless tribes in the face of American expansion. By the 1870s, the plains were littered with violated treaties as the U.S. continually “removed the Indians” from any locale where whites wanted to settle or mine.

Some Native leaders chose accommodation, believing survival lay in accepting reservation life. Others chose war. In June 1876, a confederation of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne warriors – galvanized by chiefs Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse – achieved a stunning (if temporary) victory at the Battle of Little Bighorn, annihilating Lt. Col. George Custer and about 260 of his 7th Cavalry. That triumph proved Pyrrhic; the U.S. Army redoubled its efforts, chasing down the Sioux and Cheyenne through the following year until most surrendered or fled to Canada. In October 1877, after a heroic 1,200-mile fighting retreat, the Nez Perce people of Idaho and Montana were finally cornered just shy of the Canadian border. Their leader, Chief Joseph, then surrendered in an eloquent speech that echoed across the nation’s newspapers. Exhausted and heartbroken, Joseph spoke of his fallen kin and the unbearable conditions: “I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed…The little children are freezing to death. My people… have no blankets, no food… Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”[5] His words, “I will fight no more forever,” became synonymous with the tragic fate of Native Americans in the West – a surrender not just of a battle, but of a way of life, under crushing U.S. pressure.

By the 1880s, the majority of Native Americans had been forced onto reservations, often far from their original homes. The frontier of wild tribes and open range was being replaced by a new order of fenced ranches, farms, towns, and railroads. In 1889, the government opened Oklahoma Territory – originally promised as Indian Territory – to white homesteaders in a dramatic “Land Rush,” another blow to Native claims. In 1890, the U.S. Census Bureau declared that a definable frontier line no longer existed; the American frontier was “closed.” That same year, 1890, saw the final spasm of violence that symbolically ended the Indian Wars: the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota, where U.S. troops killed over 250 Lakota Sioux – men, women, and children – who had been followers of the Ghost Dance movement. This bloodbath marked, for many historians, the end of armed Native resistance in the West.

In the aftermath, an influential historian, Frederick Jackson Turner, mused in 1893 that the frontier had been the crucible that shaped the American character – fostering individualism, democracy, and innovation – and that its closing marked the end of a formative chapter of American history. The West had been won, but at immeasurable cost to its original inhabitants.

Conclusion: Legacies of Westward Expansion

The Westward Expansion of the United States, driven by the ethos of Manifest Destiny, was a monumental saga of ambition, adventure, and adversity. In the span of less than a century, the nation grew from a narrow strip of states along the Atlantic coast into a transcontinental colossus spanning the Pacific – fulfilling what many 19th-century Americans believed was a divinely ordained mission. The pursuit of this destiny brought millions of settlers westward, each with their own story: optimistic farm families singing “Home Sweet Home” on the Oregon Trail even as they shivered in mud-soaked tents; miners toiling knee-deep in icy streams for a few glints of gold; immigrant homesteaders praying for rain on the prairie; freed slaves staking out a new life on “sacred” free soil; railroad crews driving iron through mountain and desert to bind a nation; and soldiers and warriors clashing on the plains in battles that decided the fate of a continent.

In countless diaries and letters, these people left firsthand testimonies of an era of breathtaking change. We hear pioneer women like Amelia Knight describing nights of storm where “all the tents were blown down” and mornings where “one of our best cows was taken sick and died,” leaving the carcass for the wolves. We read the exhilaration of Narcissa Whitman as her wagon party successfully fords a western river, and her empathy as curious Pawnee Indians crowd around to glimpse the strange sight of white women travelers. We have the bitter words of dispossessed chiefs: “We have neither land nor home…We are deprived of membership in the human family,” cried John Ross; “They promised to take our land and they took it,” said Red Cloud in old age[2]. And we have the poignant surrender of Chief Joseph: “My heart is sick and sad…From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”[6] These voices, woven into the narrative of Westward Expansion, reveal the human reality behind the slogans of Manifest Destiny.

For the white settlers and their descendants, westward expansion opened vast new possibilities – farms, towns, new states, and eventually great cities – fueling the rise of the United States as a global economic power. The frontier tested and often strengthened families; it produced folk heroes and rugged individualists immortalized in American lore. Yet the expansion was also built on dispossession and violence. Native American societies were shattered, reduced from freedom to dependency in the space of a generation. Entire ways of life – the horseback buffalo culture of the Plains tribes, for instance – were effectively destroyed. The environment, too, was transformed: bison nearly exterminated, rivers dammed, prairies turned to cornfields.

Other groups experienced mixed fates. Hispanic Californios and Tejanos often became second-class citizens in lands their ancestors had owned – some adapted and thrived, others lost out in the new Anglo-dominated order. African Americans, after Emancipation, found in the West both opportunity (as homesteaders, cowboys, soldiers in the “Buffalo Soldiers” regiments) and prejudice (many all-white towns barred black residents). Immigrants built much of the West – from the transcontinental railroad to frontier communities – and in doing so broadened the cultural mosaic of America, even as they faced nativism (the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, for example, halted Chinese immigration due to anti-Chinese sentiment in the West).

By 1890, the frontier was declared closed, but the legacy of Westward Expansion was just beginning to influence the American identity. The notion that the U.S. had a special mission did not fade – soon it would be applied beyond the continent (as in the Spanish–American War of 1898 and overseas imperialism). At home, the stories of pioneer perseverance became core to the national mythology of self-reliance and freedom. Yet so too did the moral reckoning – a recognition, more pronounced in later generations, of the suffering inflicted on Native Americans and the many injustices that accompanied expansion.

In the end, Westward Expansion was a complex tapestry of triumph and tragedy. The “Great Nation of Futurity” that O’Sullivan envisioned was indeed realized from sea to shining sea, replete with farms, railways, and thriving cities. But that future was purchased at a high price. As we look back, the narrative is enriched – and sobered – by hearing the personal stories of those who lived it: the pioneer mother soothing her frightened children as wolves howled on the dark prairie; the young Navajo or Cheyenne pushed into a reservation school far from home; the immigrant rail worker gazing at the vast Sierra he must bore through; the formerly enslaved farmer rejoicing to till his own soil in Kansas. These voices remind us that history is not an abstract sweep of destiny, but the lived experience of individual people. Westward Expansion is thus not only a saga of national destiny fulfilled, but also a mosaic of human lives – courageous, unjust, hopeful, heartbreaking – that together tell the full story of America’s journey west.

Sources:

- John L. O’Sullivan on “Manifest Destiny,” 1845

- Herman Melville, quote from White-Jacket, 1850

- Jefferson’s Letter to J. Breckinridge, 1803 (on Louisiana and Indian removal)

- Chief John Ross, “Memorial and Protest,” 1836 (Cherokee Nation)

- Diary of Narcissa Whitman, 1836 (Oregon Trail letter)

- Diary of Amelia Stewart Knight, 1853 (Oregon Trail)

- Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs (reflections on Mexican War)

- Letter of Samuel K. Kiefer, 1849 (California Gold Rush journey)

- “Gold Rush letter,” Dayton Daily News, Nov. 18, 1849 (mining realities)

- Excerpt from a letter by an Exoduster, 1879 (Kansas freedman)

- E.B. Crocker to C.P. Huntington, 1867 (Central Pacific RR and Chinese labor)

- Charles Crocker, testimony on Chinese strike, 1867

- Red Cloud, quoted c.1890 (Lakota), on broken promises[2]

- Surrender speech of Chief Joseph, 1877 (Nez Perce)[6]

- The American Yawp (OpenStax), “Manifest Destiny,” and primary sources, etc.

[1] Dayton in the Days of ’49

http://www.daytonhistorybooks.com/page/page/5895429.htm

[2] [3] [4] Red Cloud – Wikipedia

[5] [6] I Will Fight No More Forever | Teaching American History