A Global Institution from Antiquity to the Present

Slavery, a word heavy with moral consequence, is often portrayed in modern American discourse as a uniquely American institution, unparalleled in its barbarity and scope. While emotionally powerful, this depiction lacks historical accuracy. Slavery did not originate in America, nor was it exclusive to it, nor was American slavery the most egregious example in history. Slavery is an ancient and pervasive institution, present in nearly every civilization across time and geography, impacting societies across continents and cultures. Sadly, it persists in various forms even today. A comprehensive understanding of slavery, beyond national boundaries, is crucial for fostering a more informed perspective on this dark chapter and working towards its complete eradication.

Understanding slavery accurately does not diminish the horror of American chattel slavery. Instead, it places it within a broader global and historical framework, allowing for honest reckoning grounded in fact rather than myth.

Slavery in the Ancient World

Slavery long predates the modern era by thousands of years. Some of the earliest written laws in human history, such as the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BC), assume the existence of enslaved people as a normal part of society.¹ In ancient Mesopotamia, slaves were war captives, debtors, or criminals. Their status was permanent and hereditary.

In Ancient Egypt, slaves worked in households, agriculture, and state projects. While popular imagination associates slaves with pyramid construction, evidence suggests that most monumental building was done by paid laborers; nevertheless, slavery as an institution was firmly embedded in Egyptian society.²

In Ancient Greece, slavery was foundational to the economy and culture. Athens—often celebrated as the birthplace of democracy—relied on enslaved labor for mining, farming, domestic service, and even public administration. Aristotle explicitly defended slavery as “natural,” arguing that some people were born to rule and others to serve.³

The Roman Empire expanded slavery to an unprecedented scale. By the first century AD, enslaved people may have comprised up to one-third of the population in parts of Italy.⁴ Roman slaves worked in brutal conditions, particularly in mines and galleys, where life expectancy was often measured in months. Enslavement was typically permanent, violent, and absolute—more severe in many respects than later New World systems.

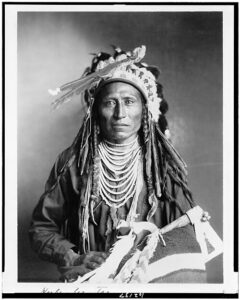

Slavery Beyond Europe

Slavery was not confined to Western civilizations. In sub-Saharan Africa, slavery existed long before European contact. African societies practiced various forms of bondage, including chattel slavery, debt slavery, and pawnship. African rulers and merchants were active participants in regional and transcontinental slave networks.⁵

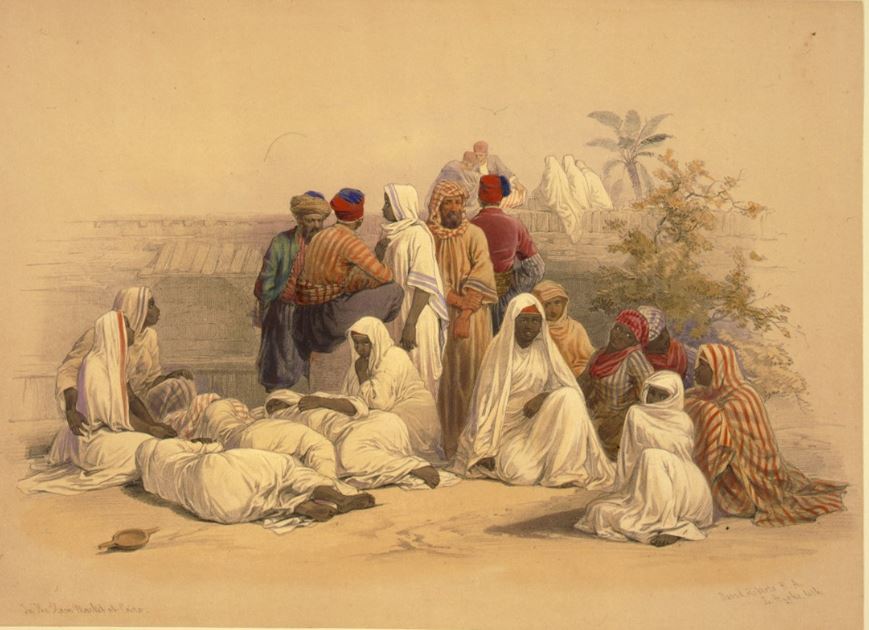

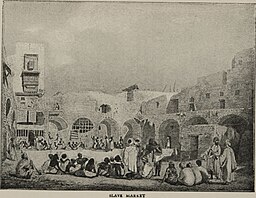

The Arab Slave Trade, which began in the seventh century and lasted well into the nineteenth century, enslaved millions of Africans, Europeans, and Asians. Unlike the Atlantic system, this trade was heavily gendered: women were often taken for domestic service or sexual exploitation, while men were frequently castrated for use as eunuchs. Mortality rates were extreme, and cultural assimilation often erased descendants entirely, leaving few modern populations tracing lineage to these enslaved peoples.⁶

In Ottoman Empire, slavery was institutionalized at the highest levels of government. The devshirme system forcibly took Christian boys from the Balkans, converted them to Islam, and trained them as soldiers or administrators. Though some rose to power, their enslavement was compulsory and traumatic, involving the destruction of family and identity.⁷

Asia also practiced slavery extensively. In imperial China, slavery existed alongside serfdom and forced labor systems for centuries. In India, caste-based servitude functioned similarly to slavery, binding generations to labor with little legal recourse.

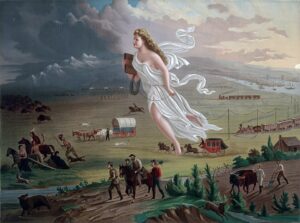

The Atlantic Slave Trade and the Americas

The Transatlantic Slave Trade emerged in the fifteenth century, driven primarily by European demand for labor in the New World. Portuguese, Spanish, British, French, and Dutch traders transported an estimated 12.5 million Africans across the Atlantic.⁸ Crucially, Africans were not seized randomly by Europeans alone; many were captured and sold by African intermediaries who controlled inland trade routes.

American chattel slavery was brutal, racialized, and hereditary. Enslaved people were legally defined as property, families were routinely separated, and physical punishment was widespread. These realities must not be minimized. However, the claim that American slavery was uniquely cruel or historically unprecedented does not withstand comparison.

Unlike many other slave systems, slavery in the United States ended relatively early. The British Empire abolished slavery in 1833. The United States followed with the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Brazil—the last major Western nation to do so—abolished slavery in 1888.⁹ In contrast, slavery persisted far longer in many parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

Slavery After Abolition

A common misconception is that slavery ended in the nineteenth century. In reality, slavery continues today in multiple forms.

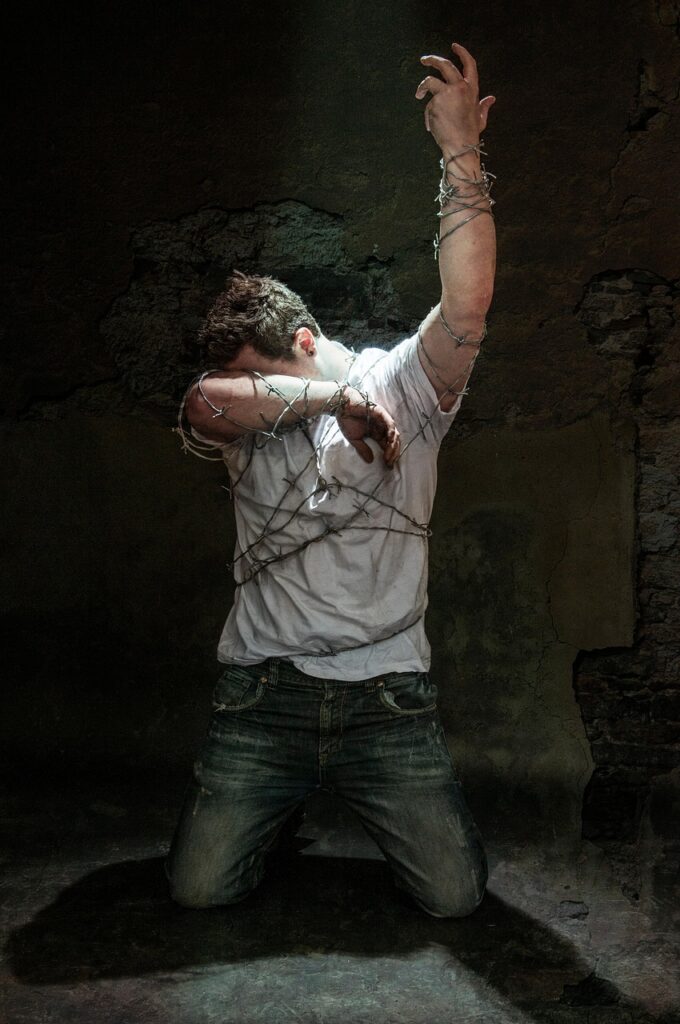

According to the International Labour Organization, over 49 million people worldwide currently live in conditions of modern slavery, including forced labor, human trafficking, debt bondage, and forced marriage.¹⁰ These practices are prevalent in parts of Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and even within Western nations.

Mauritania did not formally abolish slavery until 1981, and enforcement remains weak. In Libya, open-air slave markets were documented as recently as 2017.¹¹ North Korea operates an entire state economy built on forced labor, both domestically and abroad. None of these systems is an American creation, yet they receive comparatively little attention in popular discourse.

Why the Myth Persists

The belief that slavery was uniquely American persists for several reasons.

American slavery is a well-documented, emotionally charged, and well known aspect of U.S. national history.

Second, modern political and cultural debates often simplify history to serve present goals. Third, many educational systems emphasize Western history while neglecting global contexts, creating a distorted sense of uniqueness.

Acknowledging that slavery was global does not excuse American slavery. Rather, it restores historical accuracy and moral clarity. Slavery was a human institution, not an American one. It flourished wherever power went unchecked, and human beings were dehumanized.

Conclusion

Slavery, a dark stain on history, is not a sin unique to America, but rather a shared shame that taints the entire human story. Its insidious tendrils have wrapped around societies across the globe, leaving a legacy of suffering and injustice in their wake. From the vast ancient empires of the past to the shadowy modern trafficking networks of today, the practice of slavery has manifested in diverse forms, appearing across a multitude of cultures, spanning continents, and persisting through the long march of centuries. The United States, undeniably, participated in this abhorrent evil, contributing to the immense suffering caused by slavery. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the United States neither invented this deplorable institution nor practiced it in isolation from the rest of the world. Furthermore, while the American chapter of slavery is undoubtedly a tragic and painful part of its history, it did not reach a uniquely horrific degree when compared to the countless other instances of slavery that have occurred throughout human civilization. The sin of slavery is a global one, and its burden rests on the shoulders of humanity as a whole..

Understanding slavery as a global, enduring institution is crucial for societies to honestly confront its historical and contemporary forms and effectively work toward its eradication.

Notes

- Martha T. Roth, Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995), 71–142.

- Mark Lehner, The Complete Pyramids (London: Thames & Hudson, 1997), 220–224.

- Aristotle, Politics, Book I, trans. Benjamin Jowett (New York: Modern Library, 1943).

- Keith Bradley, Slavery and Society at Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 12–15.

- Paul E. Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Murray Gordon, Slavery in the Arab World (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1989).

- Halil İnalcık, The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age (London: Phoenix Press, 2000), 113–117.

- David Eltis and David Richardson, Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

- Seymour Drescher, Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- International Labour Organization, Global Estimates of Modern Slavery (Geneva: ILO, 2022).

- United Nations Human Rights Council, Report on Migrant Detention in Libya (2017).