Introduction

The American Civil War (1861–1865) marked a period of significant transition in military technology. Weapons ranged from outdated smoothbore muskets to advanced rifled firearms and artillery, and the battlefield witnessed the devastating consequences of both. This article examines the primary weapons used, their advantages and disadvantages, and their effects on combat and casualties.

Equipping Soldiers at the Beginning of the War

At the outset of the Civil War, few men already possessed weapons suitable for combat. While some brought personal hunting rifles or shotguns, these were often smoothbore, inaccurate at long range, and not standardized for military use. The federal and Confederate governments therefore had to supply weapons as their volunteer armies formed. The Union had the advantage of an established industrial base and federal armories, such as Springfield Armory in Massachusetts, which mass-produced the Springfield Model 1861 rifled musket. By mid-war, most Union soldiers carried standardized rifled muskets issued directly by the army.

The Confederacy, by contrast, faced shortages from the beginning. Many Confederate volunteers initially carried their own firearms, which varied widely in quality and caliber. Southern forces relied on capturing Union stockpiles, converting old muskets, and importing rifles from abroad, particularly the British Enfield Pattern 1853. The result was a lack of uniformity that persisted throughout the war. Thus, while both sides depended on government-issued weapons, the Union was able to achieve standardization far more quickly than the Confederacy, which remained chronically undersupplied【30†7 Fort Sumter & Mobilization for War.pptx】.

Muskets: Definition and Use

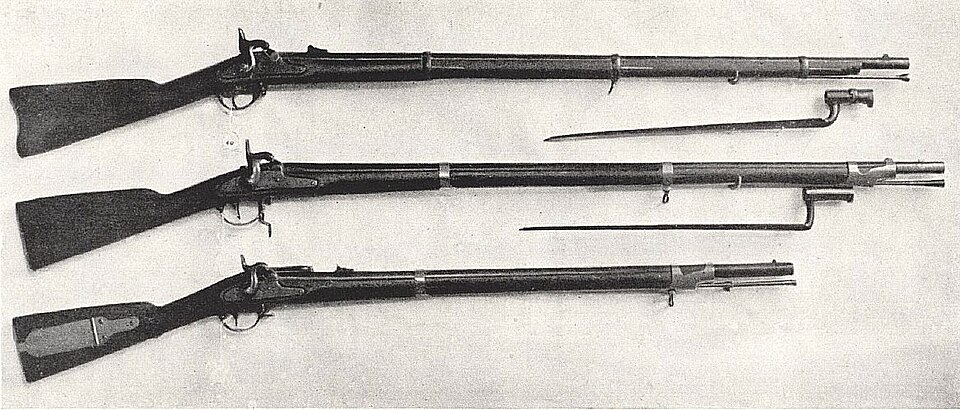

A musket was a long-barreled, shoulder-fired infantry weapon that used a smoothbore barrel and fired a round lead ball or buck-and-ball shot. Unlike rifles, muskets lacked rifling grooves, making them less accurate beyond short ranges, typically effective only within 100 yards. However, they were quicker to load than rifled weapons and devastating in massed volley fire at close quarters. Muskets had been the standard infantry arm in the United States and Europe since the seventeenth century, and by the time of the Civil War, they were still widespread. At the start of the conflict, many Union and Confederate soldiers carried older smoothbore muskets such as the Model 1816 or Model 1842 Springfield. As the war progressed, these were gradually replaced by rifled muskets, though smoothbores continued to see service, especially in Confederate units facing shortages of modern arms.

Smoothbore vs. Rifled Weapons

At the beginning of the war, many soldiers carried smoothbore muskets such as the Model 1842 Springfield. Smoothbores fired round balls or buck-and-ball ammunition, which were less accurate beyond 100 yards. The advantage was faster loading and devastating short-range effectiveness in massed volleys.

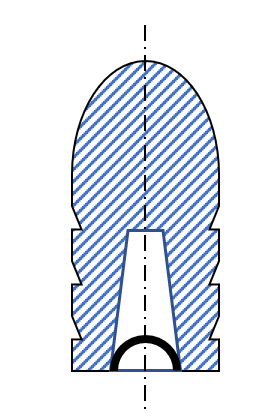

By contrast, rifled muskets, such as the Springfield Model 1861 and the British Enfield Pattern 1853, used the Minié ball. Rifling consisted of spiral grooves cut into the inside of the barrel. When the bullet was fired, these grooves imparted a spin to the projectile, stabilizing its flight. This spin greatly increased accuracy and effective range, allowing soldiers to reliably hit targets at 300–500 yards or more.

The Minié ball, designed to expand upon firing and engage the rifling grooves, made loading rifled weapons much easier than earlier rifles that required tight-fitting ammunition. The term “Minié” (pronounced min-YAY) comes from French army officer Claude-Étienne Minié, who co-developed the conical bullet in the 1840s. This innovation dramatically increased the effectiveness of rifled muskets while keeping them relatively easy to load.

However, reloading remained slow, with trained soldiers managing about three rounds per minute. Reloading a rifled musket required multiple steps: biting open a paper cartridge containing the Minié ball and pre-measured black powder, pouring the powder down the barrel, inserting the bullet wrapped in paper, ramming it securely to the breech with a ramrod, placing a percussion cap on the nipple, and then cocking the hammer. Only after these actions could the soldier fire again. Pistols required loading loose powder and ball into each chamber of the cylinder, often with a small rammer, then placing percussion caps on the nipples. The process was time-consuming, which made rate of fire limited despite the revolver’s six-shot capacity.

The adoption of rifled muskets changed battlefield tactics. Traditional massed charges became deadly, as defenders could inflict heavy casualties at long range. Despite this, commanders often employed Napoleonic tactics unsuited for such weapons, leading to immense loss of life.

Pistols and Sidearms

Officers and cavalry frequently carried pistols, the most common being revolvers such as the Colt Army Model 1860 and Remington New Model Army. These six-shot, percussion-cap revolvers offered repeating firepower but were less accurate at long range. The drawback was the reliance on black powder and percussion caps, which were vulnerable to moisture and required slow reloading once all chambers were fired.

Although revolvers were widely known and many civilians, especially in the South and on the frontier, purchased sidearms before the war, they were not universally carried by ordinary citizens. In the armies, pistols were not standard issue for regular infantry soldiers. Instead, they were primarily issued to officers, cavalrymen, and artillerymen. Common soldiers who carried pistols usually brought them from home, purchased them personally, or acquired them during service. Because of their limited range and slow reloading, pistols were mainly used in close combat or by mounted troops, while infantrymen relied overwhelmingly on muskets and bayonets.

Ammunition and Bullet Production

Civil War armies used paper cartridges prepared in arsenals or by contractors. These cartridges combined a Minié ball and a powder charge, simplifying the loading process. While soldiers could mold bullets themselves using lead and bullet molds—especially in the Confederacy when shortages arose—most ammunition was supplied by government armories and depots. Not all bullets were the same caliber. The standard Union Springfield Model 1861 fired a .58 caliber Minié ball, while the British Enfield Pattern 1853, widely imported by both sides, used a .577 caliber bullet. The difference was slight enough that ammunition could often be interchanged, but it was a continual logistical concern. Standardization was more effective in the Union, while the Confederacy faced more frequent mismatches of weapons and ammunition.

Black Powder Limitations

All small arms of the Civil War, including both muskets and pistols, relied on black powder as their propellant. This powder produced dense smoke that obscured vision and fouled barrels. The residue made reloading increasingly difficult over time and required frequent cleaning. Both muskets and pistols were affected by this problem, although in different ways: muskets required careful loading with powder, bullet, and ramrod, while pistols used percussion caps and loose powder for each chamber. In both cases, the reliance on black powder meant that moisture could ruin ammunition, the battlefield could quickly fill with smoke, and the weapons themselves would become less reliable the longer they were used without maintenance. The slow rate of fire and vulnerability to weather made black powder weapons consistently difficult to manage in combat.

Artillery: Cannons and Ammunition

Artillery played a decisive role in the Civil War. Smoothbore cannons such as the 12-pounder Napoleon were widely used, firing round shot, shell, case shot, and canister. A cannon was typically identified by the weight of a solid iron ball it could fire—hence the term “12‑pounder,” which meant the gun was designed to fire a 12‑pound solid shot. Other common sizes included 6‑pounders, 10‑pounder Parrott rifles, and 3‑inch Ordnance rifles, the latter named for the diameter of their bore rather than the projectile’s weight. This system of labeling provided both armies with a practical way to distinguish cannon size, bore, and the type of ammunition required.

Round shot, solid iron balls, could smash through fortifications or ranks of men. Explosive shells caused fragmentation injuries. Case shot, or shrapnel shells, exploded in midair, releasing deadly fragments. Canister, a tin can filled with iron balls, turned a cannon into a giant shotgun, devastating at close range.

Rifled artillery, including the Parrott rifle and the 3‑inch Ordnance rifle, offered greater accuracy and range. However, rifled barrels were prone to bursting under heavy use. Artillery inflicted catastrophic injuries, tearing limbs and causing traumatic amputations.

Carnage and Battlefield Injuries

The destructive power of Civil War weaponry produced unprecedented carnage. Minié balls, with their soft lead and heavy mass, shattered bones on impact, often pulverizing limbs beyond repair. A hit to an arm or leg usually necessitated amputation, since the shattered bone fragments and massive tissue damage made clean healing nearly impossible. When the bullet struck the torso, it could tear through organs, leading to fatal internal injuries. Wounds to the head were almost always lethal. Soldiers who survived gunshot wounds often faced infection, since germ theory and antiseptic practices were not yet in common use.

Artillery fire inflicted even more horrifying wounds. Round shot could tear a man apart, decapitating or severing limbs instantly. Shells and case shot scattered iron fragments that ripped through flesh, causing multiple penetrating injuries. Canister, fired at close range, acted like a giant shotgun blast, shredding ranks of soldiers with dozens of small iron balls. Survivors of artillery wounds frequently endured amputations, disfigurement, or lifelong disability. Medical practices lagged behind, and battlefield hospitals were overwhelmed by the sheer scale of traumatic injuries. The combination of outdated tactics with modern rifled weapons and artillery created staggering casualties—over 600,000 dead and many more wounded.

Conclusion

The Civil War represented a crossroads of military technology, blending outdated smoothbore muskets with modern rifled firearms and advanced artillery. The shift from rudimentary to cartridge-based weapons would come after the war, but the conflict already demonstrated the lethal power of rifled arms and explosive ordnance. The human cost reflected not only the effectiveness of these weapons but also the inability of strategy and medicine to keep pace with technological change.

Bibliography

Brayton, Matthew. Weapons of the Civil War. New York: Chelsea House, 2009.

Coggins, Jack. Arms and Equipment of the Civil War. New York: Doubleday, 1962.

Nosworthy, Brent. The Bloody Crucible of Courage: Fighting Methods and Combat Experience of the Civil War. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2003.

Stevenson, James R. Civil War Guns: The Complete Story of Federal and Confederate Small Arms, Their Manufacture, Use, and Impact on the War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001.

Watts, Steven. The Civil War Soldier: A Historical Reader. New York: Routledge, 2012.

“Fort Sumter & Mobilization for War.” Class PowerPoint. 【30†7 Fort Sumter & Mobilization for War.pptx】.